Throughout history, the relationship between nomadic peoples and horses has been one of the most profound partnerships between humans and animals. This dynamic bond transformed how nomadic societies traveled, hunted, fought, and ultimately survived in some of Earth’s most challenging environments. From the windswept steppes of Central Asia to the expansive Great Plains of North America, horses became not just transportation but the central pillar around which entire cultural identities formed. The horse’s strength, speed, and adaptability complemented human intelligence and tool-making abilities, creating a revolutionary symbiosis that allowed nomadic peoples to thrive in landscapes where settled agricultural communities struggled. This article explores the multifaceted ways horses enabled nomadic survival across diverse cultures and environments, revealing how this partnership shaped human history and continues to influence traditional societies today.

Origins of Horse Domestication

Horse domestication represents one of the most transformative developments in human history, with archaeological evidence pointing to initial domestication occurring approximately 5,500-6,000 years ago in the Eurasian steppes, particularly in what is now Kazakhstan and Ukraine. Before this pivotal development, nomadic peoples were limited by their own mobility, typically traveling on foot with possessions carried by hand or on the backs of dogs. The domestication process likely began with horses first being used as a food source, with nomadic hunters gradually realizing the animals’ potential for carrying loads and, eventually, riders. DNA and archaeological studies suggest that early domesticated horses were selectively bred for docility, strength, and endurance – traits that would prove essential for nomadic lifestyles in harsh environments. This domestication process didn’t happen overnight but evolved over generations as humans and horses developed increasingly sophisticated means of communication and cooperation.

Revolutionary Mobility Advantages

The integration of horses into nomadic cultures dramatically transformed human mobility capabilities, effectively shrinking vast landscapes and expanding the range of territory groups could utilize. On horseback, humans could travel up to 50 miles per day – roughly four times the distance possible on foot – allowing nomads to access broader territories for grazing, hunting, and seasonal migration. This enhanced mobility proved particularly valuable in harsh environments like the Eurasian steppes, where resources were widely scattered and seasonal variations demanded regular movement. Horses also enabled nomads to relocate entire camps quickly when threatened by enemies or environmental hazards, providing a crucial survival advantage against both human and natural threats. Furthermore, mounted nomads could transport substantially more possessions and supplies than their pedestrian counterparts, allowing for more comfortable survival with larger family units and the accumulation of culturally meaningful possessions that would have been impossible for foot travelers.

The Horse in Warfare and Defense

Horses revolutionized warfare for nomadic societies, creating asymmetrical advantages that often allowed numerically smaller nomadic groups to dominate larger sedentary populations. The development of mounted archery – the ability to shoot arrows accurately while riding at speed – became the signature military tactic of peoples like the Scythians, Mongols, and Huns, allowing them to strike with devastating effect and withdraw before enemies could respond effectively. Horses also provided tactical flexibility that was previously impossible, with nomadic forces able to conduct lightning raids, envelop enemy flanks, or withdraw rapidly when faced with superior forces. For defensive purposes, mounted scouts could provide early warning of approaching threats, giving communities crucial time to prepare defenses or relocate vulnerable members. The intimidation factor of mounted warriors cannot be overstated, with historical accounts from China, Persia, and Rome describing the psychological impact of facing highly mobile horse warriors whose battlefield presence seemed to defy conventional military wisdom of the time.

Horses as Survival Resources

Beyond transportation and warfare, horses served as walking larders for many nomadic groups, providing critical resources necessary for survival in harsh environments. Many nomadic peoples, including Mongolian and Kazakh tribes, incorporated horse milk (kumis) into their diets, a nutrient-rich food source containing proteins, fats, and vitamins that could be fermented for preservation. Horse blood, mixed with milk, was consumed in emergency situations by warriors like the Mongols when other food sources were unavailable during extended campaigns. The meat from horses provided high-calorie sustenance in extreme climates, with some groups practicing careful slaughter methods that maximized the use of every part of the animal. Beyond consumption, horses provided materials for essential tools and shelter, with their hides being processed into weather-resistant coverings for dwellings, water-resistant boots, and durable containers, while horsehair was woven into ropes and cords of exceptional strength.

Cultural Adaptations Around Equine Partnerships

The integration of horses into nomadic life catalyzed profound cultural adaptations that shaped everything from social structures to religious beliefs. Marriage practices in many nomadic societies incorporated bride prices paid in horses, establishing important alliances between family groups while ensuring redistribution of wealth and genetic diversity in horse herds. Children were typically taught riding skills from extremely young ages, with historical accounts describing Mongol children being strapped to horses before they could walk, creating a population where virtually every member possessed advanced riding abilities. Specialized clothing evolved specifically for mounted lifestyles, including split trousers for riding (which eventually influenced clothing in settled societies like China) and boots designed specifically for comfortable use in stirrups. Religious and spiritual practices often centered around horses, with many nomadic groups practicing elaborate horse burial rituals, as seen in Scythian tombs, and incorporating horse imagery into their cosmological understandings of the universe.

Technological Innovations in Riding Equipment

The development of specialized horse-related technology profoundly impacted nomadic survival capabilities over centuries of innovation. The invention of the composite bow – made from layers of wood, horn, and sinew – created a weapon perfectly suited for mounted archery, combining power with the compact size necessary for use on horseback. The development of the stirrup, which spread through nomadic cultures before reaching settled societies, revolutionized mounted combat by allowing riders to stand in the saddle, delivering more powerful blows and maintaining better balance during combat maneuvers. Specialized saddles designed for specific purposes evolved within different nomadic cultures, with some optimized for long-distance travel and others for warfare, herding, or hunting specific game animals. Bridle designs reflected sophisticated understanding of horse psychology and physiology, with different bit types allowing riders precise control appropriate to different tasks and environments, demonstrating the deep knowledge nomads developed about their equine partners.

Horse Management in Extreme Environments

Nomadic peoples developed sophisticated horse management techniques uniquely adapted to extreme environments where conventional stabling and feeding would have been impossible. In the harsh winters of Mongolia and Siberia, horses were seldom provided with supplemental feed, instead being selectively bred for the ability to forage by digging through snow with their hooves to reach dormant grasses – a behavior known as “pawing” that domestic horses from other regions typically cannot perform effectively. During summer migrations, nomadic herders carefully managed grazing pressure through constant movement, preventing overgrazing while maximizing the nutritional value their horses could extract from sparse vegetation. Water management became a critical skill, with herders possessing detailed knowledge of seasonal water sources across vast territories and planning migrations accordingly to ensure their horses never lacked this essential resource. Many nomadic groups practiced selective breeding focused on hardiness and endurance rather than size or speed, creating regionally adapted horse types uniquely suited to local environmental challenges.

The Horse Economy and Wealth Measurement

Horses functioned as the central pillar of economic systems for nomadic societies, serving simultaneously as productive assets, currency, status symbols, and stores of wealth. Among groups like the Kazakh and Kyrgyz peoples, a man’s wealth was measured primarily by the size of his horse herd, with particularly fine breeding stallions representing significant capital investment comparable to land ownership in agricultural societies. Complex systems of horse trading evolved, with specialized knowledge about bloodlines, performance characteristics, and suitability for specific tasks commanding premium prices in inter-tribal trading networks. Horses facilitated economic specialization by enabling the transport of goods between distant communities, allowing nomadic groups to trade for resources unavailable in their immediate territory. In many nomadic societies, horse theft was considered among the most serious crimes, reflecting not just the animal’s economic value but its essential role in survival – a person without a horse in the vast steppes or plains faced potentially life-threatening vulnerability.

Horses in Hunting Strategies

Mounted hunting revolutionized nomadic food acquisition strategies, dramatically expanding the range and efficiency of protein procurement. Horses allowed hunters to pursue game animals like deer and antelope that could easily outrun humans on foot, with some nomadic groups developing elaborate techniques for exhausting prey through sustained pursuit across long distances. The elevated position of mounted hunters improved visibility across vast plains and steppes, making it easier to locate herds and coordinate group hunting tactics. Among North American Plains tribes like the Comanche and Lakota, complex buffalo hunting techniques evolved that relied on horseback riders herding buffalo toward prepared killing grounds or over cliffs in highly coordinated group efforts. In Central Asia, some nomadic hunters practiced a form of hunting partnership with trained eagles or falcons, using horses to position themselves strategically while birds of prey executed the actual kill – a sophisticated multi-species hunting system that maximized success rates in challenging environments.

Communication and Social Organization

Horses facilitated sophisticated communication networks that transformed how nomadic societies organized themselves across vast territories. Mounted messengers could travel tremendous distances to share critical information about resources, threats, or social gatherings, creating connections between widely dispersed family groups that would have been impossible to maintain on foot. Among Mongol groups, a sophisticated relay system called the Yam allowed messages to travel up to 200 miles per day through a network of horse stations – a speed of information transmission unrivaled in the pre-modern world. The mobility provided by horses supported flexible social groupings, with nomadic bands able to aggregate into larger units when resources were abundant or defense was necessary, then disperse into smaller family groups when conditions required it. Leadership structures in many nomadic societies reflected equestrian skill, with riding ability and horse management knowledge being essential qualities for individuals who aspired to positions of influence and authority within their communities.

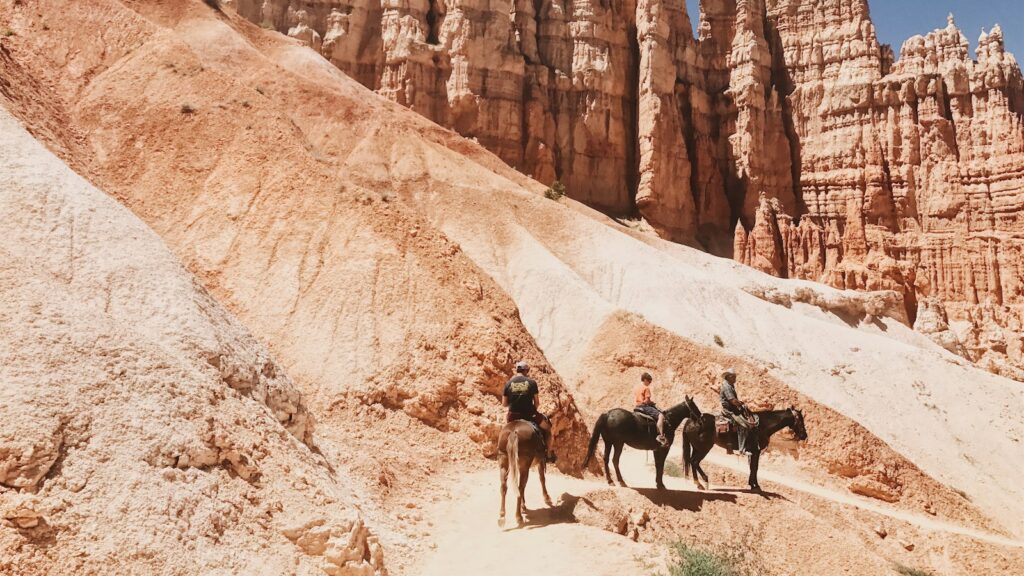

Seasonal Migration Strategies

Horses enabled sophisticated seasonal migration patterns that maximized resource utilization across diverse landscapes while minimizing environmental degradation. In mountainous regions like the Altai, horses allowed nomadic herders to practice vertical transhumance – moving livestock between high summer pastures and protected lower valleys during winter months – covering distances and elevations that would be impossible with family groups traveling on foot. The speed and carrying capacity of horses permitted nomads to time their movements precisely with seasonal resource availability, arriving at specific locations to coincide with plant growth cycles, animal migrations, or reliable water availability. Among groups like the Mongols, migrations could cover hundreds of miles annually, with horses carrying disassembled dwellings (gers/yurts), household goods, and vulnerable family members across challenging terrain. The horse’s biological adaptability to diverse environments meant nomadic peoples could traverse multiple ecological zones within a single seasonal cycle, extracting optimal resources from each before moving on – a survival strategy uniquely enabled by equine partnerships.

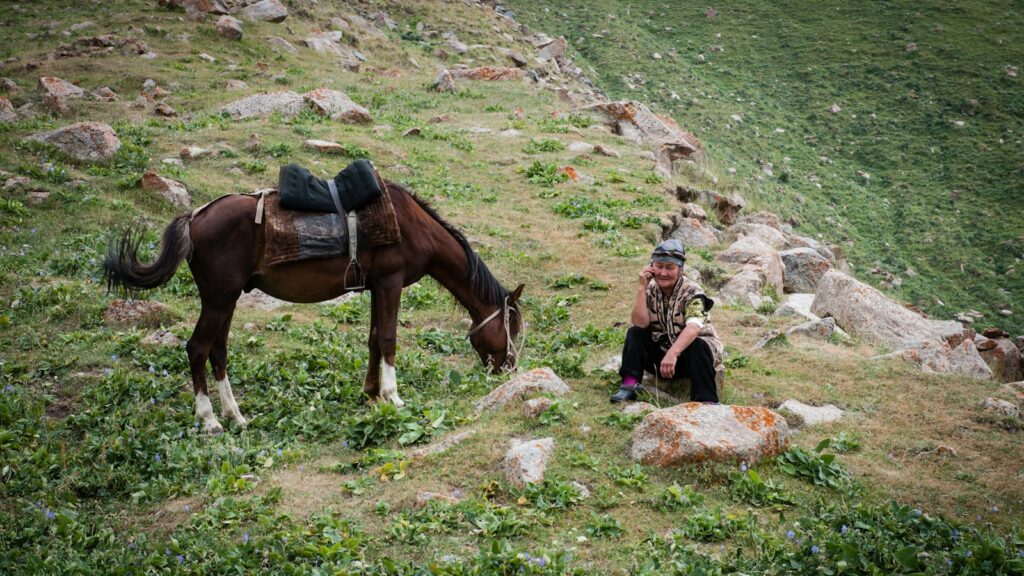

Modern Survival of Horse-Nomadic Traditions

Despite modernization pressures, several contemporary communities maintain horse-centered nomadic traditions that continue to demonstrate the efficacy of these ancient survival strategies. In Mongolia, approximately 30 percent of the population continues some form of nomadic lifestyle, with horses remaining central to both practical survival and cultural identity, particularly in the western regions where mechanized transport remains challenging. Kazakhstani eagle hunters still practice traditional mounted hunting techniques in the Altai Mountains, preserving both the practical skills and cultural knowledge associated with this specialized form of horse-based subsistence. Climate change concerns have renewed interest in nomadic knowledge systems, with researchers studying traditional migration patterns and horse management techniques as potentially sustainable adaptations to increasingly variable environmental conditions. Organizations like the International Association for the Preservation of the Mongolian Horse work to maintain genetic diversity in indigenous horse populations that retain the hardiness and environmental adaptations developed through centuries of nomadic breeding practices.

Legacy and Historical Impact

The horse-nomad partnership fundamentally altered the course of world history, creating power dynamics that shaped the development of major civilizations across Eurasia. The threat posed by mounted nomadic groups directly influenced the construction of massive defensive works like the Great Wall of China, representing enormous investments of resources specifically to counter the military advantages horses provided to nomadic peoples. Genetic studies reveal the profound demographic impact of horse-enabled nomadic expansions, with Y-chromosome evidence suggesting that approximately 0.5 percent of the world’s male population carries genetic markers attributable to the Mongol expansion – a distribution only possible through the mobility horses provided. Technologies developed by nomadic peoples for horse management and riding eventually transferred to settled societies, with innovations like the stirrup revolutionizing warfare across Europe and Asia. Languages, cultural practices, and genetic contributions from nomadic horse peoples persist in populations across a vast geographic range, demonstrating how this human-animal partnership created historical impacts disproportionate to the often small population sizes of nomadic groups themselves.

Conclusion

The relationship between nomadic peoples and horses represents one of history’s most successful adaptive strategies, allowing humans to thrive in environments that would otherwise prove challenging or impossible to inhabit. This partnership transcended mere utility, becoming the foundation for distinct cultural identities, sophisticated technological innovations, and effective survival systems finely tuned to specific environmental conditions. As contemporary societies face increasing environmental uncertainties, the knowledge systems developed by horse nomads offer valuable insights into sustainable resource management and adaptive flexibility. While traditional horse-nomadic lifestyles have diminished in the modern era, their legacy persists not only in the genetic and cultural makeup of numerous populations but also in our understanding of how human-animal partnerships can fundamentally transform survival possibilities in challenging environments. The horse-human relationship among nomadic peoples stands as a powerful reminder of how interspecies cooperation has shaped human history and may continue to inform our adaptation strategies in an uncertain future.