Long before the arrival of European conquistadors, horses held a marginal presence in South American indigenous cultures, with their fossilized ancestors having disappeared from the continent thousands of years earlier. However, with the Spanish colonization in the 16th century, horses were reintroduced to the Americas, profoundly transforming indigenous cultures across the continent. Despite their relatively recent return, horses quickly became integral to the spiritual, economic, and cultural frameworks of many indigenous South American societies. From the Mapuche warriors of Chile to the nomadic peoples of the Argentine pampas, horses transcended their utilitarian purpose to become powerful symbols of identity, status, and cosmological significance. This article explores the most iconic equine figures and traditions across indigenous South American cultures, highlighting the remarkable adaptation and integration of horses into pre-existing worldviews and practices.

The Reintroduction of Horses to South America

The story of horses in indigenous South American cultures begins not with their arrival but with their return. Paleontological evidence suggests that horses originated in the Americas before migrating to Eurasia and Africa, only to become extinct in their native lands approximately 10,000-12,000 years ago. When Spanish conquistadors reintroduced horses to South America in the early 16th century, they unknowingly initiated one of the most profound cultural transformations in indigenous history. Unlike many European imports, horses were eagerly adopted by numerous indigenous groups who recognized their practical and strategic value. By the late 1600s, escaped or stolen Spanish horses had formed feral populations throughout the continent, allowing independent access to horses for indigenous peoples far from colonial settlements. This reintroduction created what anthropologists call the “horse complex” – the rapid and comprehensive integration of horses into indigenous lifeways, fundamentally altering mobility, warfare, hunting, and social organization.

The Mapuche Horse Warriors

Among the most renowned indigenous horse cultures of South America are the Mapuche people of central and southern Chile and southwestern Argentina. The Mapuche’s extraordinary adaptation to equestrian warfare allowed them to successfully resist Spanish colonization for over 300 years, making them one of the most effective indigenous resistance movements in history. The iconic Mapuche warrior rode bareback or with minimal tack, often controlling the horse primarily through leg pressure and weight shifts. Special breeding programs developed horses suited for warfare – compact, strong animals with exceptional endurance and agility. The relationship between Mapuche warriors and their horses was so intimate that horses were often included in funeral rites, with some evidence suggesting the occasional sacrifice of a warrior’s favorite mount to accompany him in the afterlife. The Mapuche horse culture developed specialized terminology and hierarchies based on equestrian skill, with expert riders holding positions of significant prestige in the community.

The Sacred White Horses of the Andes

Throughout the Andean indigenous cultures, white horses hold a position of particular spiritual significance, often associated with celestial deities and cosmic power. In many Quechua and Aymara communities, white horses became integrated into pre-existing cosmological frameworks that emphasized the duality of upper and lower worlds. The white horse, due to its color and Spanish origins, became associated with the upper world (hanan pacha) and celestial forces. During important religious festivals in regions of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, white horses often play ceremonial roles, sometimes carrying effigies of saints or sacred objects in processions that blend indigenous and Catholic traditions. Some Andean legends describe supernatural white horses that emerge from lakes or mountains, serving as messengers between the human and spirit worlds. These sacred associations demonstrate how indigenous groups integrated the horse not just as a practical tool but as a meaningful symbolic element within their existing spiritual frameworks.

The Tehuelche and Ranquel Horse Nomads

The Tehuelche and Ranquel peoples of Patagonia and the Argentine pampas developed some of the most sophisticated nomadic horse cultures in South America. For these groups, horses facilitated a transition from primarily pedestrian hunter-gatherers to highly mobile equestrian societies that could cover vast distances in pursuit of game and resources. Tehuelche horsemen developed specialized technologies, including distinctive saddles made from multiple layers of guanaco hides and unique stirrups crafted from hardwood. Children learned to ride almost as soon as they could walk, creating a deeply embodied knowledge of horsemanship that shaped physical development and cultural identity. The horse-centered lifestyle of these groups influenced everything from dwelling construction (making them more portable) to clothing design (developing specialized riding gear including the iconic leather boots and distinctive ponchos). The Tehuelche in particular became renowned for their horsemanship skills, with historical accounts describing their ability to control horses at full gallop while hanging from the side of the animal to use the horse’s body as a shield during combat.

Horses in Indigenous Trade Networks

The integration of horses transformed pre-existing indigenous trade networks across South America, creating new economic opportunities and power dynamics among various cultural groups. In the southern cone regions, horses themselves became valuable trade commodities, with specialized breeding knowledge becoming a form of intellectual capital. Indigenous groups who mastered horsemanship, like the Mapuche and Tehuelche, established expansive trade networks spanning the Andes mountains, exchanging horses and horse-related goods for materials unavailable in their territories. The horse-facilitated trade allowed for the movement of heavier goods over longer distances, enabling the exchange of items like metal tools, textiles, and agricultural products across previously insurmountable geographic barriers. For many communities, particularly in the Pampas and Patagonia, horses became a measurement of wealth and a form of currency, with certain animals of exceptional quality or coloration commanding extraordinary value in indigenous economic systems.

The Horse in Guaraní Mythology

The Guaraní people, indigenous to parts of present-day Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Bolivia, integrated horses into their rich mythological framework in fascinating ways that demonstrate cultural adaptation and syncretism. Unlike some other indigenous groups who could maintain greater distance from Spanish colonizers, many Guaraní communities experienced intensive Jesuit missionary presence, creating a complex blending of indigenous and European religious elements. In Guaraní cosmology, horses sometimes appear as manifestations of nature spirits called “jasy jatere” – supernatural beings who could shape-shift between equine and human forms. Some Guaraní stories describe mystical horses that emerge from sacred waters or forests, carrying messages from ancestral spirits or serving as psychopomps – guides between the worlds of the living and the dead. Certain Guaraní healing traditions incorporate elements of horse symbolism, with shamanic practitioners sometimes using horse hair or symbolic horse figures in curing rituals for specific ailments.

Horse Domestication Practices Among the Aymara

The Aymara people of the Altiplano regions of Bolivia, Peru, and Chile developed distinctive horse-keeping practices adapted to the challenging high-altitude environment where they live. Unlike lowland equestrian groups, the Aymara integrated horses into a pre-existing domesticated animal complex that included llamas and alpacas, creating a multi-species herding strategy. Aymara horse training techniques often begin with very young foals, using gentle but persistent handling methods that create strong human-animal bonds without breaking the animal’s spirit. Traditional Aymara horse gear reflects practical adaptations to their mountainous habitat, featuring reinforced saddles with high cantles for stability on steep slopes and specialized bridles designed to provide precise control during precarious mountain traversals. Aymara communities developed intricate calendar systems governing breeding, training, and veterinary care for their horses, with specific ceremonies marking important transitions in a horse’s life from birth to training to working maturity.

Criollo Horses and Cultural Identity

The Criollo horse, descending from Spanish stock but shaped by centuries of adaptation to South American environments and indigenous breeding practices, has become an iconic symbol of cultural identity for many indigenous and mestizo communities. Recognized for their exceptional hardiness, disease resistance, and adaptability to diverse terrains from mountains to marshlands, Criollos embody a living history of indigenous horse management. For many communities, particularly across Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Chile, the distinctive characteristics of locally developed Criollo lineages represent tangible connections to ancestral knowledge and regional identity. Traditional selective breeding by indigenous groups emphasized practical traits like surefootedness, calm temperament, and thermal regulation capabilities rather than the speed or appearance standards favored in European breeding traditions. The resulting Criollo horse types carry unique genetic signatures influenced by generations of indigenous management, representing living repositories of biocultural knowledge worthy of conservation efforts from both cultural heritage and biodiversity perspectives.

Equestrian Art and Craft Traditions

The integration of horses into indigenous cultures spawned rich artistic and craft traditions that continue to this day across many South American communities. The Mapuche developed sophisticated silverwork techniques specifically for creating elaborate horse gear, including distinctive spurs, bridle fittings, and ceremonial breastplates that signaled the rider’s status and spiritual protection. In the Andean regions, textile traditions adapted to incorporate equestrian themes, with weavers creating specialized saddle blankets and horse coverings featuring symbolic designs that combined pre-Columbian motifs with equestrian elements. Indigenous leatherworking traditions flourished with the adoption of horses, developing into highly specialized crafts with regional variations in technique and decorative elements from the braided rawhide work of the pampas to the embossed leather of Andean communities. These artistic expressions represent more than functional objects – they embody complex cultural narratives about identity, adaptation, and the transformation of indigenous lifeways following the integration of the horse.

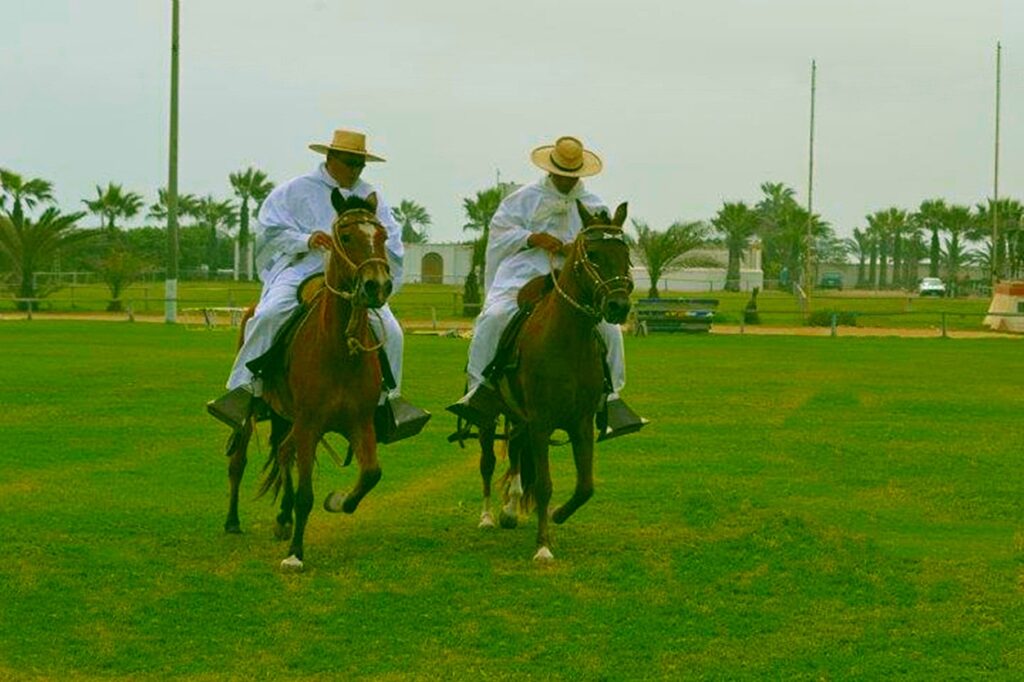

Contemporary Horse Festivals and Rituals

Many contemporary indigenous communities maintain vibrant horse-centered festivals and rituals that demonstrate the ongoing cultural significance of equines in South American indigenous identities. In southern Chile, the Mapuche Nguillatun ceremony often features horseback processions where community members circle ritual spaces in specific patterns that reflect cosmological principles while mounted on specially adorned horses. The famous Yawar Fiesta (Blood Festival) of highland Peru, while controversial for animal welfare reasons, represents a complex ritual expression where the horse symbolizes Spanish colonial power in conflict with indigenous resistance represented by the condor. In parts of northeast Argentina and southern Brazil, the Guaraní-influenced “Festival of Saint John” features horse blessing ceremonies and midnight rides that combine Catholic elements with indigenous spiritual practices related to purification and protection. These living traditions demonstrate how horse ceremonies have become important vehicles for cultural continuity and identity expression in contemporary indigenous communities across South America.

Women’s Relationships with Horses in Indigenous Cultures

While historical accounts often emphasize male warriors and hunters, indigenous women across South America developed significant and sometimes specialized relationships with horses that deserve recognition. Among certain Mapuche communities, women maintained distinctive riding styles and specialized tack designed for female riders, sometimes including side-saddles influenced by Spanish styles but adapted to indigenous needs and aesthetics. In many Andean communities, women played critical roles in breeding decisions and the early training of foals, developing embodied knowledge about equine behavior and health that constituted important intellectual traditions passed through female lineages. The Tehuelche women of Patagonia were known to be exceptional riders in their own right, with specific equestrian skills related to the transportation of household goods during seasonal migrations and specialized techniques for riding while carrying infants or young children. These gendered dimensions of indigenous horse relationships challenge simplistic narratives about equestrian cultures while highlighting the comprehensive way horses were integrated into all aspects of community life.

Threats to Indigenous Horse Traditions

Despite their cultural importance, many indigenous horse traditions face significant challenges in the twenty-first century. Economic pressures, land dispossession, and forced sedentarization have disrupted traditional horse-keeping practices in many communities, making it difficult to maintain breeding programs or provide adequate grazing for horses. Climate change poses existential threats to certain indigenous horse-keeping traditions, particularly in the Altiplano regions where drought and unpredictable weather patterns impact the availability of forage and water for horses. In some regions, youth outmigration to urban areas has created generational gaps in horse knowledge transmission, with fewer young people learning traditional horsemanship skills, breeding knowledge, or craft techniques related to horse gear production. Conservation efforts by cultural heritage organizations and indigenous rights groups are working to document and preserve these traditions, recognizing that indigenous horse knowledge represents valuable biocultural heritage with relevance for sustainable development, climate adaptation, and cultural identity preservation.

The Legacy and Future of Indigenous Horse Cultures

The profound relationship between indigenous South American peoples and horses continues to evolve in the modern context, demonstrating remarkable resilience and adaptability. Many indigenous communities are actively reclaiming and revitalizing horse traditions as part of broader cultural sovereignty movements, establishing cultural education programs where elders teach traditional horsemanship to younger generations. Indigenous knowledge about local horse breeds, including their adaptation to specific environments and disease resistance, has attracted attention from veterinary scientists and conservation biologists seeking sustainable approaches to equine management in changing climatic conditions. Several indigenous communities have developed cultural tourism initiatives centered around their equestrian heritage, creating economic opportunities while maintaining control over how their traditions are presented and interpreted. These contemporary expressions demonstrate that indigenous horse cultures are not static relics of the past but living, evolving traditions that continue to hold profound meaning and practical value in the twenty-first century context.

The iconic horses of indigenous South American cultures represent far more than mere transportation or tools for warfare and hunting. They embody complex processes of cultural adaptation, resistance, and creativity in the face of colonization and environmental challenges. From the fierce independence of Mapuche warriors to the spiritual symbolism of Andean white horses, these equine traditions illuminate how indigenous peoples actively shaped their relationships with introduced species to serve their own cultural needs and worldviews. As contemporary indigenous communities work to preserve and revitalize their equestrian heritage, these iconic horses continue to serve as powerful symbols of cultural continuity, adaptation, and resilience. By recognizing the sophistication and significance of indigenous horse knowledge, we gain not only a deeper understanding of South American cultural history but also important insights into sustainable human-animal relationships that may prove valuable for addressing present-day challenges.