Beneath the hoofprints of modern trail riders lie paths trodden by some of history’s most significant figures and events. These historic horse trails, once vital transportation routes, military paths, or migration corridors, now offer riders a chance to literally follow in the footsteps of history. From routes used by indigenous peoples for centuries to paths carved by pioneers and settlers, these trails preserve our collective heritage while providing breathtaking recreational experiences. Today’s equestrians can experience the same terrain, views, and sometimes even challenges that historical figures once faced, creating a unique connection between past and present. This article explores some of the most historically significant horse trails still accessible to riders today, offering glimpses into their storied pasts and practical information for those wishing to experience these living museums from the saddle.

The Pony Express Trail

Perhaps no horse trail in American history captures the imagination quite like the Pony Express route, which operated for just 18 months between April 1860 and October 1861 but left an indelible mark on the nation’s identity. This 1,966-mile trail stretched from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, carrying mail and communications across the frontier in a remarkable ten days. Today, riders can follow substantial portions of this historic route through Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California, with the Bureau of Land Management maintaining marked segments particularly through Nevada and Utah. The trail passes through diverse landscapes from prairie to desert to mountain passes, often following the same river corridors and geographic features that guided the original riders. Travelers should prepare for remote conditions on many segments, as the historic isolation that made the Pony Express necessary in the first place still characterizes parts of the route today.

The Santa Fe Trail

For nearly 60 years, the Santa Fe Trail served as one of America’s first international trade routes, connecting Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico (then part of Mexico) across 900 miles of diverse terrain. Established in 1821, the trail became a crucial commercial highway that facilitated cultural exchange and territorial expansion before gradually being replaced by the railroad. Modern riders can experience significant portions of this National Historic Trail, with particularly well-preserved sections in Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico still showing wagon ruts carved into the prairie nearly two centuries ago. The Mountain Route through Raton Pass offers challenging but rewarding riding with spectacular views similar to those witnessed by 19th-century traders. Annual trail rides organized by historical societies frequently travel segments of the trail, offering guided experiences complete with historical interpretation and overnight camping reminiscent of the original journey.

The Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail represents one of the largest voluntary migrations in human history, with over 400,000 settlers traveling its 2,170-mile length between 1843 and 1869 in search of new opportunities in the Pacific Northwest. While much of the original trail has been covered by modern development, substantial sections remain accessible to riders, particularly in Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon. The National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center in Baker City, Oregon, serves as an excellent starting point for riders, with multiple trail access points nearby including the pristine ruts at Virtue Flat. Riders traversing the trail today can ford the same rivers, climb the same passes, and witness landmarks like Independence Rock and Chimney Rock that served as navigational beacons for pioneers. The Bureau of Land Management and various historical organizations maintain maps specifically for equestrians interested in experiencing authentic sections of this iconic migration route.

The Anza Trail

Long before the American frontier pushed westward, Spanish colonizers established crucial routes through what is now the American Southwest. The Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail commemorates the 1775-76 expedition that brought 240 colonists from Mexico to establish San Francisco, covering 1,200 miles through what is now Arizona and California. Modern equestrians can follow substantial portions of this trail, enjoying a journey through desert landscapes, coastal mountains, and along the Pacific shoreline while experiencing terrain virtually unchanged since Anza’s expedition. The trail is particularly well-maintained through Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in California, where riders can camp under the same star-filled skies that guided the original colonists. Cultural sites along the way, including Spanish missions and indigenous communities with centuries of continuous habitation, provide context and depth to the riding experience.

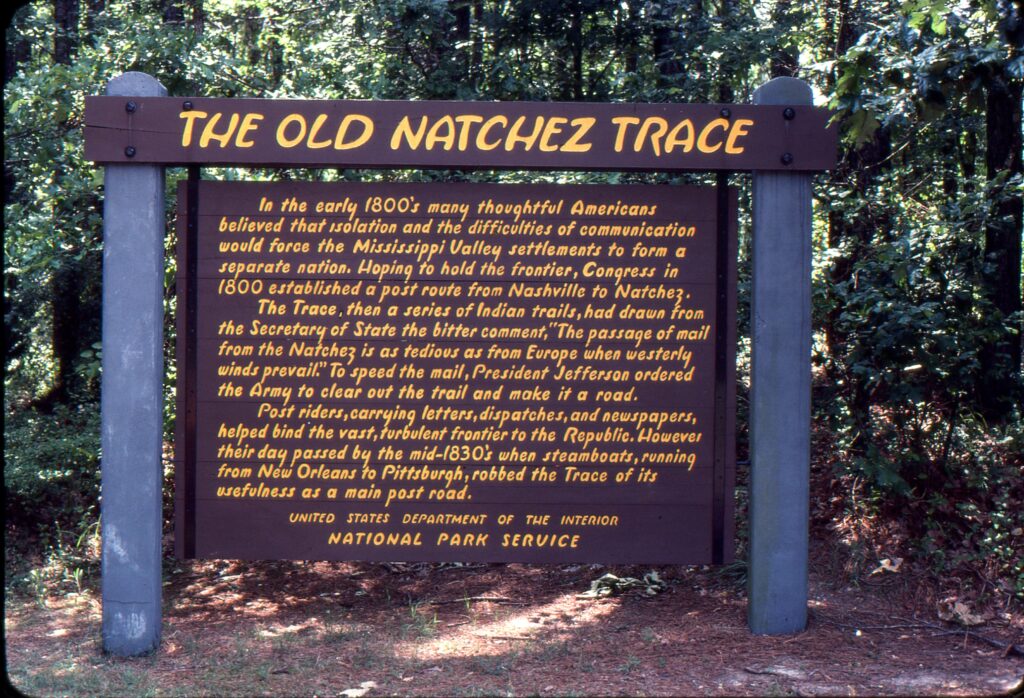

The Natchez Trace

Originally formed by game trails and Native American footpaths, the Natchez Trace developed into a vital 440-mile transportation corridor connecting Natchez, Mississippi to Nashville, Tennessee. For thousands of years before European settlement, indigenous peoples used this route for trade and communication, and by the late 1700s, American settlers began using it as a return route after floating goods downriver to New Orleans. Today, the Natchez Trace Parkway parallels much of the historic footpath, with the National Park Service maintaining numerous horse trails that follow or intersect with the original trace. The Rocky Springs section in Mississippi offers particularly excellent riding opportunities through forests virtually unchanged since travelers on foot and horseback navigated the area centuries ago. Unlike many western historic trails, the Natchez Trace passes through predominantly hardwood forests with abundant water sources, making it ideal for multi-day rides in spring and fall when temperatures are moderate.

The California Trail

Branching off from the Oregon Trail near Fort Hall in present-day Idaho, the California Trail carried approximately 250,000 gold seekers and settlers to California during the mid-19th century, particularly following the 1848 gold discovery at Sutter’s Mill. This 2,000-mile route traversed some of North America’s most challenging terrain, including the formidable Sierra Nevada mountains where the Donner Party met their tragic fate in 1846-47. Modern riders can experience significant portions of this historic route, with particularly well-preserved sections in Nevada where trail ruts remain visible across the high desert landscape. The California Trail Interpretive Center near Elko, Nevada, provides orientation for riders interested in exploring nearby trail segments, including the pristine sections through the Ruby Mountains. Riding the California Trail today offers not only a connection to history but also access to some of the most spectacular and remote landscapes in the American West, where conditions can still challenge modern travelers much as they did the original pioneers.

The Cherokee Trail of Tears

While many historic trails represent exploration and opportunity, the Cherokee Trail of Tears stands as a solemn reminder of displacement and injustice, commemorating the forced relocation of the Cherokee Nation from their ancestral southeastern homelands to designated territory in present-day Oklahoma between 1838 and 1839. This 5,043-mile network of water and overland routes saw thousands of Cherokee people travel on foot and horseback, with approximately 4,000 perishing during the journey. Today, riders can follow segments of the northern route through Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, with particularly well-preserved sections in the Mark Twain National Forest and Pea Ridge National Military Park. Annual memorial rides organized by Cherokee Nation representatives offer guided experiences with cultural and historical context, allowing participants to honor those who suffered while learning about Cherokee heritage and resilience. These rides typically incorporate traditional ceremonies and storytelling, creating a profound educational experience alongside the physical journey.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

Predating the famous trails of the American frontier by centuries, El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (The Royal Road of the Interior Land) served as the primary north-south route through New Spain from Mexico City to San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico, from 1598 to 1882. This 1,600-mile route facilitated Spanish colonization, missionary efforts, and commerce through some of North America’s most challenging desert terrain for nearly 300 years. Modern riders can experience significant portions of this historic route in New Mexico, where the Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service maintain trail segments with interpretive signage. The section passing through Jornada del Muerto (Journey of the Dead Man), a 90-mile waterless desert stretch, gives modern equestrians a genuine sense of the challenges faced by colonial travelers, though today’s riders benefit from established water caches and camping facilities. Annual historic reenactment rides organized by cultural heritage groups travel portions of the trail, often stopping at historic missions and settlements established along this ancient route.

The Old Spanish Trail

Connecting Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Los Angeles, California, the Old Spanish Trail served as a vital trade route from 1829 to 1848, carrying woolen goods from New Mexico to California and returning with horses and mules. This 2,700-mile network of trails traversed some of North America’s most forbidding terrain, crossing six modern states and navigating deserts, mountains, and canyons that tested the limits of human and equine endurance. Today, equestrians can access numerous sections of this National Historic Trail, with particularly remarkable riding opportunities in southern Utah and Nevada where the landscape remains largely unchanged since the days of Mexican traders and American mountain men. The Virgin River segment near St. George, Utah, offers spectacular rides through red rock canyons with visible trail remnants dating to the 1830s. Because much of the trail crosses public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service, extended pack trips along authentic route segments are possible with proper permits and preparation.

The Outlaw Trail

Less an officially designated path and more a network of rugged hideouts and escape routes, the Outlaw Trail stretched from Montana to Mexico through the most remote regions of the American West, serving notorious figures like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This loosely defined corridor followed natural features that provided escape routes and hiding places, including the Hole-in-the-Wall in Wyoming, Brown’s Park in Colorado, and Robbers Roost in Utah. Modern riders can experience sections of this legendary trail network, particularly in Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains and Utah’s San Rafael Swell, where isolated canyons and mesa tops still feel remarkably removed from civilization. Guided outfitters offer specialized “outlaw” themed rides that incorporate storytelling about famous heists and escapes while traversing the same challenging terrain that once sheltered some of America’s most wanted criminals. The remote nature of these rides means participants often experience multi-day pack trips with primitive camping, creating an authentic connection to this colorful chapter of western history.

The Great Western Trail

Once the primary route for moving Texas Longhorn cattle to railheads in Kansas and markets as far north as Canada, the Great Western Trail operated from 1874 to 1893, witnessing the movement of over seven million cattle and horses during its heyday. Unlike the more famous Chisholm Trail to the east, the Great Western Trail traversed more arid terrain through western Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana, eventually extending into Saskatchewan. Today, riders can follow substantial portions of this historic cattle highway, particularly in Texas where the Texas Historical Commission has placed markers along the route. The segment passing through Palo Duro Canyon State Park offers spectacular riding through colorful badlands where trail drivers once navigated their herds through challenging terrain. Annual cattle drive reenactments in several states allow riders to participate in living history experiences, complete with authentic chuck wagons, cowboy cooking, and overnight camping under the stars just as the original drovers experienced during the golden age of the open range.

The Mormon Pioneer Trail

Between 1846 and 1868, more than 70,000 members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveled the 1,300-mile Mormon Pioneer Trail from Nauvoo, Illinois, to Salt Lake City, Utah, seeking religious freedom and new settlement opportunities. This carefully planned migration included handcart companies alongside traditional wagon trains, creating one of the most organized mass movements in American history despite the harsh conditions encountered along the route. Modern riders can experience significant portions of this historic trail, with particularly well-preserved sections in Wyoming where the sweetwater valley and South Pass appear much as they did to 19th-century travelers. The Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail crosses five states, with interpretive centers in Nebraska and Wyoming providing context for trail riders. Annual commemorative rides organized by church-affiliated groups follow authentic trail segments, often incorporating historical journals and accounts that bring the experiences of original pioneers to life for participants.

Preparing for Historic Trail Riding

Riding historic trails requires preparation beyond typical recreational trail riding, as these routes often pass through remote areas with limited services and variable conditions. Riders should obtain detailed maps specific to horse travel, as many historic trails cross multiple jurisdictions including private property requiring advance permission. Careful planning for water access is essential, particularly on western trails where natural sources may be scarce or seasonally dependent; many experienced historic trail riders cache water in advance or arrange support vehicles to meet at designated points. Weather considerations vary dramatically by region and season, with desert trails often best ridden in spring or fall while northern routes may be limited to summer access due to snow at higher elevations. Connecting with historical societies and trail associations dedicated to specific routes can provide invaluable information about current conditions, access points, and opportunities to join organized group rides with historical interpretation and logistical support.

Conclusion

The opportunity to ride historic horse trails offers a unique intersection of outdoor recreation, historical education, and cultural connection. Whether following in the hoofprints of Pony Express riders racing against time, Mormon pioneers seeking religious sanctuary, or indigenous traders establishing networks of commerce and communication centuries before European arrival, today’s equestrians can experience history in a visceral, immersive way impossible to replicate through books or museums alone. These living monuments to our shared past continue to provide not just recreational opportunities but also important perspective on the development of nations and cultures across North America. As development and changing land use threaten some historic corridors, organizations dedicated to preserving these trails work tirelessly to ensure future generations of riders can continue to experience these pathways through history from the most authentic vantage point possible—the back of a horse.