The introduction of horses to South America fundamentally altered the continent’s historical trajectory, empowering indigenous civilizations and colonial powers alike. Before Spanish conquistadors arrived in the early 16th century, the Inca Empire and other native civilizations had built impressive societies without equine assistance, relying instead on llamas and human porters for transportation. However, when horses galloped onto the scene, they catalyzed a transformation in warfare, trade, agriculture, and cultural identity that would reshape empires and forge new ones. From the Pampas of Argentina to the Andean highlands, horses became instruments of conquest and resistance, symbols of status and freedom, and essential partners in the expansion of territories and influence. This article explores the multifaceted ways in which these magnificent animals influenced the rise and fall of South American empires, forever changing the continent’s political, economic, and social landscape.

The Arrival of Horses in South America

Horses first reached South American shores aboard Spanish ships during the conquests of the early 16th century, with documented arrivals dating back to 1535 when Pedro de Mendoza brought horses to what is now Argentina. These initial equine immigrants were predominantly Andalusian breeds, known for their strength and adaptability, traits that would prove crucial in the challenging and diverse South American terrain. Prior to this pivotal introduction, no equine species had existed on the continent since the extinction of native horses approximately 10,000 years earlier during the Late Pleistocene period. The conquistadors’ horses were initially few in number and jealously guarded as strategic military assets, with laws prohibiting indigenous peoples from owning or riding them in many regions. However, through escapes, raids, trading, and eventually breeding, horses gradually dispersed throughout the continent, setting the stage for profound transformations in power dynamics and empire building.

Military Revolution: Horses in Conquest and Defense

The military advantages conferred by horses dramatically altered the balance of power in South America, initially giving Spanish conquistadors an overwhelming tactical edge against indigenous empires. Mounted Spanish soldiers could move rapidly across diverse terrain, charge with devastating force, and quickly retreat if necessary—capabilities that terrorized Inca forces who had never encountered such mobility in warfare. The psychological impact of these mounted warriors was equally significant, as many indigenous accounts describe the horse and rider as a frightening, supernatural entity that inspired fear before combat even began. As native groups eventually gained access to horses, they developed their own unique cavalries and combat techniques, particularly in regions like the Pampas and Patagonia where the Mapuche and other groups became formidable mounted warriors. The Mapuche successfully resisted Spanish domination for centuries, using adaptive cavalry tactics that transformed them from a vulnerable population into a powerful military force capable of defending and even expanding their territories. This military revolution fundamentally changed how empires could be defended, conquered, or expanded across the continent.

Transportation and Communication Networks

Horses revolutionized transportation and communication systems throughout South America, enabling empires to maintain control over vast territories that previously proved challenging to administer. The Spanish colonial empire established an extensive network of routes where mounted couriers could deliver messages and small goods at unprecedented speeds, covering distances in days that would have taken weeks by foot. This improved communication system allowed for more efficient governance, quicker responses to threats, and better coordination of economic activities across expansive imperial holdings. Indigenous empires that adopted horses similarly expanded their reach, with groups like the Mapuche developing trade networks spanning both sides of the Andes Mountains—a feat that would have been nearly impossible without equine transportation. Horse-drawn carts and wagons further transformed the transportation of goods, allowing for greater volumes of trade products, agricultural surplus, and military supplies to move across imperial territories. The ability to rapidly deploy administrators, tax collectors, and military forces throughout an empire’s domain proved essential to maintaining control over far-flung provinces and newly conquered territories.

Economic Transformation through Equine Power

The introduction of horses catalyzed significant economic changes that fueled imperial expansion, particularly through agricultural intensification and mining development. Horse-drawn plows could cultivate larger areas than human-powered methods, increasing agricultural productivity and supporting larger populations that could be mobilized for imperial projects. In mining operations, particularly the silver mines of Potosí that funded the Spanish Empire, horses and mules transported ore and supplies, allowing for expanded production that would have been impossible with human porters alone. New economic activities emerged around horse breeding, with specialized ranches (haciendas) developing to supply military horses, transportation animals, and agricultural workhorses to various markets throughout South American empires. The horse-based pastoral economy that emerged in regions like the Pampas created new wealth and power centers that sometimes operated independently from imperial authorities, developing into influential regional forces. These economic transformations generated surplus resources that could be channeled into imperial expansion, military campaigns, and the construction of impressive urban centers that demonstrated imperial power and prestige.

Frontier Expansion and Territorial Control

Horses enabled both colonial and indigenous empires to extend their influence into frontier regions that previously remained beyond effective control due to distance and harsh environments. Spanish colonists pushed into the vast grasslands of the Pampas and Gran Chaco, establishing ranches and settlements that gradually expanded imperial borders far beyond the initial coastal footholds. Indigenous groups like the Araucanians used their newly acquired cavalry to defend existing territories and expand into new lands, pushing back against Spanish encroachment and even crossing the Andes to raid and settle in new regions. The mobility provided by horses allowed imperial powers to establish outposts in strategic frontier locations, creating buffers against rival empires and indigenous resistance while securing access to natural resources. Control of horse-suitable terrain became a significant factor in imperial strategy, with grasslands and open valleys taking on new strategic importance because they facilitated rapid deployment of mounted forces for territorial control. This horse-powered frontier expansion fundamentally reshaped the map of South American empires, creating new borders, contested zones, and spheres of influence that would form the foundations of modern South American nations.

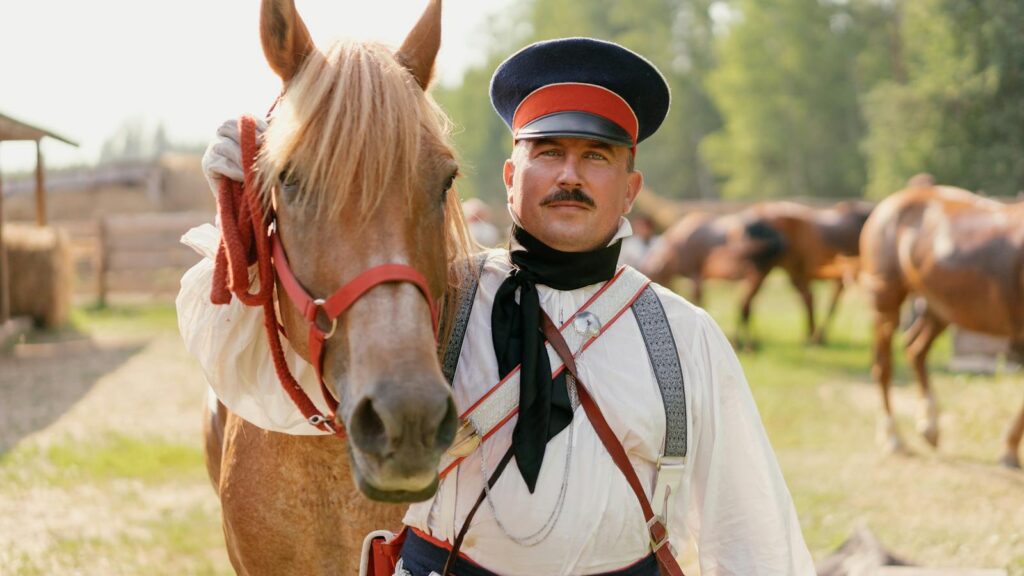

Cultural Transformation and Identity Formation

Beyond practical applications, horses catalyzed profound cultural transformations that reshaped imperial identities and social structures across South America. Indigenous groups who mastered horsemanship, like the Mapuche, Tehuelche, and later the Araucanian confederations, developed new cultural identities centered around equestrian skills, with horsemanship becoming integral to their cosmology, social status systems, and coming-of-age rituals. The Spanish colonial empire developed the distinctive culture of the gaucho in the southern grasslands, creating a horseback frontier society that, while nominally under imperial control, developed its own unique identity that would later influence national cultures in Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil. Horses became powerful status symbols in both colonial and indigenous societies, with specialized tack, riding styles, and horse breeds signifying social rank and imperial authority. Religious and ceremonial practices incorporated horses, from the adoption of mounted patron saints like Santiago Matamoros (St. James the Moor-slayer) by colonial forces to the integration of horses into indigenous spiritual practices and burial customs. These cultural transformations reinforced imperial hierarchies while simultaneously creating new identities that sometimes challenged imperial control, demonstrating the complex role horses played in South American empire building.

Demographic Shifts and Population Movement

The adoption of horses facilitated major demographic shifts that reshaped imperial populations and settlement patterns across South America. Mounted indigenous groups could migrate more efficiently in response to environmental pressures or military threats, allowing for strategic population movements that preserved cultural cohesion even under imperial pressure. The Spanish Empire established a network of horse-accessible settlements and ranches that attracted colonists to frontier regions, creating population centers that solidified imperial claims to contested territories. Horse-based pastoralism enabled sustainable human presence in grassland regions previously considered marginal for agriculture, allowing empires to populate and claim territories that would otherwise remain beyond effective control. Horses facilitated larger-scale population relocations, such as the Spanish reducciones policy that forcibly concentrated indigenous populations into controlled settlements, and the defensive migrations of indigenous groups fleeing colonial expansion. These demographic shifts fundamentally altered the human geography of South American empires, creating new patterns of settlement, resource use, and cultural exchange that would endure long after the imperial era ended.

The Rise of Horse-Centered Indigenous Empires

Perhaps the most dramatic impact of horses was their role in enabling the creation and expansion of indigenous empires that successfully challenged European colonial control. The Araucanian Confederacy in present-day Chile and Argentina transformed from localized chiefdoms into a powerful confederated empire capable of resisting Spanish domination for over 300 years, largely due to their mastery of horse warfare and horse-based economic adaptations. In the Pampas region, the Ranquel people established a horse-centered empire that controlled vast territories and trade routes, effectively limiting Spanish and later Argentine expansion until the late 19th century. The Tehuelche in Patagonia developed a mobile equestrian empire spanning enormous territories, controlling trade networks and natural resources while maintaining cultural independence from European influence. The Comanche in the northern frontiers of Spanish America (though technically beyond South America proper) demonstrated the empire-building potential of horse adoption, creating what some historians have termed a “Comanche Empire” that dominated the southern Plains and challenged multiple European powers simultaneously. These indigenous equestrian empires represented a direct counterforce to European colonial expansion, demonstrating how the adopted technology of the horse could be turned against its introducers to create alternative imperial models based on mobility, raid economies, and territorial control.

Horse Breeding and the Development of South American Breeds

The expansion of South American empires was supported by sophisticated horse breeding programs that developed specialized equine populations adapted to local conditions and imperial needs. The Spanish colonial authorities established royal studs that bred military horses with the stamina and temperament needed for conquest and control, carefully selecting for traits that would perform well in varied South American environments. Indigenous empires like the Mapuche developed their own breeding programs, creating smaller but incredibly hardy mountain horses capable of navigating difficult Andean terrain while carrying warriors and their equipment. The Criollo horse emerged as a distinct South American breed, renowned for its endurance and adaptability, becoming the backbone of transportation, agriculture, and military operations throughout multiple empires. Regional variations in breeding priorities created specialized horse populations, from the agile cutting horses favored by gauchos in the Pampas to the sure-footed mountain horses of the Andean regions. These breeding developments represented significant technological adaptations that enhanced imperial capabilities, allowing both colonial and indigenous powers to maximize the military and economic potential of their equine resources in ways that directly supported territorial control and expansion.

Technological Innovations in Horse Equipment

South American empires developed specialized horse equipment that enhanced their ability to utilize horses for imperial expansion and control. The Spanish-American recado saddle evolved from European designs to better suit the needs of colonial vaqueros and soldiers, featuring modifications that allowed riders to remain mounted for extended periods while working cattle or patrolling imperial borders. Indigenous groups like the Mapuche invented distinctive bridle designs and decorative silver tack that not only served practical purposes but also indicated status within their expanding confederations. The development of the distinctive South American lasso and bolas (throwing weapons consisting of weights connected by cords) allowed mounted hunters and warriors to capture animals and enemies from horseback, technologies that proved particularly useful in controlling the vast grasslands regions. The boleadoras weapon, perfected by Pampas riders, became an effective tool for both hunting and warfare, allowing mounted warriors to entangle enemies or prey from a safe distance. These technological innovations represent important adaptations that enhanced the utility of horses for imperial purposes, demonstrating how both European and indigenous empires modified existing technologies to maximize equine contributions to their expansion efforts.

Resistance and Counter-Empire Movements

Horses played a central role in indigenous resistance movements that directly challenged imperial expansion in South America. The Great Araucanian Revolt of the 16th century, in which Mapuche forces under leaders like Lautaro captured Spanish horses and adapted Spanish cavalry tactics, halted the southern expansion of the Spanish Empire and established a resistant indigenous power that would endure for centuries. Tupac Amaru II’s 1780 rebellion against Spanish rule in Peru utilized mounted forces to rapidly spread the insurgency across vast territories, demonstrating how horses enabled resistance movements to coordinate across the challenging geography of the Andes. In the Pampas and Patagonia, mounted indigenous confederations conducted sophisticated raiding economies that targeted Spanish and later Argentine settlements, effectively controlling imperial expansion through counter-force. The mobility provided by horses allowed resistance leaders to escape capture, regroup after defeats, and maintain communication networks that sustained long-term opposition to imperial control. These horse-powered resistance movements fundamentally shaped the boundaries and nature of South American empires, forcing colonial powers to adapt their strategies, negotiate rather than simply conquer, and ultimately accept limits to their territorial ambitions.

Environmental Impacts of Horse-Driven Expansion

The equine-powered expansion of South American empires triggered significant environmental changes that altered landscapes and ecosystems across the continent. The introduction of large herds of horses and cattle to the Pampas grasslands transformed vegetation patterns through selective grazing, compaction of soils, and seed dispersal, creating new ecological conditions that favored imperial ranching economies. Indigenous empires like the Mapuche adapted to these environmental changes by developing sophisticated range management practices that sustained their horse herds while preserving crucial grassland resources. The demand for horse feed and pasturage drove deforestation in some regions, as expanding empires cleared woodland to create additional grazing areas to support their essential equine military and transportation resources. Water management systems were developed or expanded to support horse populations in drier regions, with imperial authorities and indigenous leaders alike constructing reservoirs and irrigation systems that remain visible on the landscape today. These environmental modifications facilitated imperial expansion by creating landscapes more conducive to horse-based transportation, military operations, and economic activities, demonstrating how ecological transformation often went hand-in-hand with imperial ambition in horse-powered South American empires.

The Legacy of Equine Empires in Modern South America

The profound influence of horses on South American imperial expansion continues to shape the continent’s nations, cultures, and identities to this day. Modern political boundaries in countries like Chile, Argentina, and Brazil partially reflect the territorial limits established during the era of horse-powered imperial competition, with frontier zones contested between mounted indigenous empires and European colonial powers often becoming the borders between contemporary nations. Cultural traditions centered around horsemanship remain integral to national identities, from Argentina’s gaucho heritage to Chile’s huaso culture, reflecting the enduring social impact of equestrian empires. Economic patterns established during the era of horse-powered expansion continue to influence land use and ownership, particularly in the vast ranching estates that evolved from imperial-era horse breeding operations and cattle haciendas. Indigenous communities that developed powerful equestrian traditions during their resistance to imperial expansion, such as the Mapuche, continue to incorporate horseback skills and horse symbolism into their cultural practices and identity formation. The legacy of these equine empires remains visible across South America’s cultural landscape, demonstrating how profoundly these magnificent animals shaped not only the continent’s imperial past but also its national present.

Conclusion

The introduction of horses to South America catalyzed one of history’s most remarkable transformations, fundamentally altering the trajectory of empires across the continent. From the Andean highlands to the vast Pampas, horses empowered both conquest and resistance, enabling unprecedented territorial control while simultaneously providing tools for indigenous autonomy. They revolutionized warfare, transportation, agriculture, and cultural identity, creating new imperial possibilities while reshaping existing power structures. The legacy of these equine partnerships endures in modern South American national boundaries, cultural traditions, and environmental landscapes. Perhaps most significantly, the story of horses in South American empire-building demonstrates the complex, often unexpected consequences of technological transfers between cultures—how the very animals that initially facilitated European conquest ultimately enabled indigenous resistance and the creation of alternative imperial models. This equine revolution forever changed the face of a continent, leaving an indelible mark on the empires that rose and fell across South America’s diverse landscapes.