The American West conjures images of dusty plains, tumbleweeds, and lawmen on horseback pursuing outlaws across rugged terrain. In this frontier landscape, where formal judicial systems were often sparse or nonexistent, horses played an integral role in the administration of justice. These magnificent animals weren’t merely transportation; they were essential partners in maintaining law and order during a tumultuous period of American history. From the pursuit of criminals to the execution of sentences, horses were inextricably linked to how justice was sought, delivered, and sometimes denied in the Old West. Their contribution to the western justice system reveals much about the practical realities, cultural values, and moral complexities of frontier life between the mid-1800s and early 1900s.

The Horse as the Lawman’s Most Valuable Asset

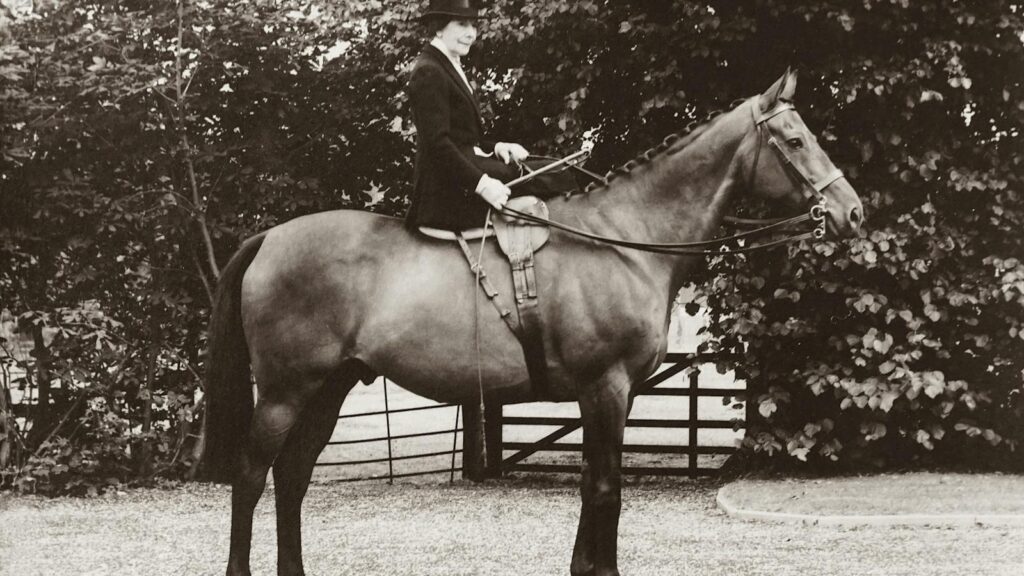

In territories where sheriffs and marshals might be responsible for maintaining law across hundreds of square miles, a reliable horse was more than transportation—it was a deputy of sorts. Lawmen carefully selected horses with stamina, intelligence, and steady temperaments that could handle the unpredictable scenarios of pursuit and confrontation. These animals needed to remain calm during gunfire, navigate challenging terrain, and maintain speed over long distances when tracking fugitives. The relationship between a lawman and his horse was often deeply personal, with some horses serving the same officer for many years and developing an intuitive understanding of commands and situations. Contemporary accounts frequently mention how particular horses became locally famous for their role in capturing notorious criminals, sometimes earning as much respect as their human partners.

Mounted Posses and the Extension of Community Justice

When serious crimes occurred, horses enabled the rapid formation and deployment of posses—groups of citizens temporarily deputized to assist in pursuing criminals. These mounted groups could cover extensive territory, tracking outlaws who might otherwise escape justice in the vast western landscapes. The posse represented a democratic extension of legal authority, allowing ordinary citizens to participate directly in law enforcement when formal resources were limited. Horses made these pursuits possible, creating a mobile law enforcement network that could respond quickly to crimes, even in remote areas. The cultural significance of the posse ride became so embedded in western mythology that it persisted as a symbol of community justice long after formal court systems were established throughout the territories.

Horse Theft as a Capital Offense

In the hierarchy of western crimes, horse theft was considered among the most serious offenses, often punishable by death—a severity that underscores the animal’s essential role in frontier society. Unlike other property crimes, stealing a horse could indirectly cause death by stranding someone in harsh environments or preventing crucial medical care from reaching isolated communities. The severity of punishment reflected both the practical value of horses and their symbolic importance as markers of mobility and independence in Western culture. Historical records document numerous instances of horse thieves being hanged by vigilante groups without formal trials, highlighting how the protection of equine property transcended formal legal structures. This harsh response to horse theft remained common even as more structured legal systems developed in western territories, demonstrating the unique position these animals held in the moral economy of frontier justice.

Mounted Police Forces and Territorial Control

Specialized mounted police forces like the Texas Rangers and later the U.S. Mounted Border Patrol established authority over vast territories largely due to their superior horsemanship and carefully selected mounts. These elite units developed specific breeding and training programs to create horses that could withstand the rigors of desert patrols, river crossings, and extended pursuits. Mounted officers typically cover 50-60 miles daily in regular patrols, a range impossible for foot patrols and crucial for maintaining a presence in disputed or lawless regions. The psychological impact of mounted officers was significant—their elevated position, mobility, and ability to arrive unexpectedly gave them tactical advantages in confrontations and enhanced their authority in interactions with civilians. The distinctive relationship between these specialized forces and their horses created a model of frontier law enforcement that influenced police organizations throughout the developing West.

Horses and the Spectacle of Public Justice

Public executions in the Old West frequently involved horses, particularly in hanging ceremonies where the condemned would be mounted on horseback before the animal was led or startled away, leaving the person suspended. This macabre role established horses as unwitting participants in the theater of justice that characterized many frontier communities, where executions served as both punishment and public warning. The presence of horses at these events added a dramatic element that reinforced the connection between justice and the practical realities of western life. Historical accounts describe how crowds would gather to witness these spectacles, with the horse’s sudden departure becoming the pivotal moment in the execution process. The use of horses in this manner reflected the pragmatic approach to justice in communities where formal execution infrastructure was often lacking, repurposing an everyday tool for judicial ends.

The Pursuit Advantage: Horses and Criminal Apprehension

Horses provided lawmen with critical advantages in tracking and apprehending criminals across difficult western terrains. A well-trained horse could follow trails through environments ranging from desert hardpan to mountain passes where mechanical transportation would later prove impossible. Lawmen became skilled at reading their horses’ reactions, as the animals often detected hidden fugitives through keen senses of smell and hearing that complemented human tracking skills. The stamina of Western law horses was legendary, with documented cases of pursuits lasting several days over hundreds of miles without replacement mounts. This pursuit capability fundamentally shaped western justice by dramatically reducing the territory in which criminals could expect to escape consequences, effectively shrinking the vastness of the frontier from a justice perspective.

Breed Selection and the Evolution of Law Horses

The requirements of frontier justice influenced horse breeding practices throughout the western territories, with certain bloodlines becoming prized for law enforcement work. Quarter Horses gained particular favor among lawmen for their acceleration over short distances—crucial for closing gaps during pursuits—while Morgans and certain Thoroughbred crosses were valued for endurance in long-distance tracking. Many successful sheriffs and marshals maintain small breeding programs, selecting for traits like intelligence, low spooking threshold, and the ability to work calmly in chaotic environments. Historical records from territorial prison systems and law enforcement agencies reveal an increasing sophistication in horse selection criteria as frontier justice systems became more formalized. By the late 19th century, some jurisdictions had established specific physical and temperament standards for law enforcement mounts, creating the foundation for modern police horse programs.

Horses as Witnesses to Justice and Injustice

In numerous recorded cases, horses became silent witnesses to both the administration of justice and its miscarriage in frontier communities. Court records from the western territories contain numerous instances where horse behavior was introduced as evidence, such as a horse’s reaction to a suspect or its tracks placing an individual at a crime scene. In communities where formal evidence was often scarce, reliable patterns of horse movement and behavior sometimes provided crucial investigative leads. More troublingly, horses were often present at extrajudicial killings and lynchings, their tracks sometimes becoming the only physical evidence of vigilante actions that circumvented proper legal processes. The diaries and letters of frontier judges occasionally mention the uncomfortable awareness that horses had observed more true justice and injustice than most human witnesses would ever testify to.

Cavalry Justice and Military Law Enforcement

The U.S. Cavalry represented a formal extension of federal authority in the West, with mounted soldiers frequently serving as the primary law enforcement presence in contested territories. These cavalry units enforced not only military regulations but often civilian laws in regions where other authority structures were absent or ineffective. The horse-centered tactical capabilities of cavalry units made them particularly effective at responding to large-scale disorder like land disputes, civil unrest, or conflicts between settlers and indigenous populations. Military horse training programs established standards that influenced civilian law enforcement practices, particularly regarding mount selection, care, and tactical deployment in challenging environments. The relationship between military justice and civilian authority was often complex and contentious, with the superior mobility of cavalry units sometimes creating tensions around jurisdiction and the appropriate use of force in frontier communities.

Transportation for the Accused: Horses and Prisoner Movement

Before motorized transport, horses provided the primary means of moving arrested individuals to trial locations or imprisonment, a practical reality that shaped procedural justice in significant ways. Long journeys by horseback with restrained prisoners created physical challenges that influenced how arrest procedures developed, including specialized restraint methods that balanced security with the need to navigate difficult terrain on horseback. The journey to justice became a significant phase in the judicial process, with some historical accounts describing how these extended transports sometimes allowed for informal interrogation or even reconsideration of charges against the accused. For many prisoners, these mounted journeys represented their last experience of freedom before confinement or execution, a psychological reality captured in numerous folk songs and prisoner narratives from the period. In remote areas where formal jails were unavailable, secured horses sometimes served as temporary restraint systems, with prisoners tied to saddle horns or specialized “prisoner saddles” designed for secure transport.

Iconic Mounted Lawmen and Their Legacy

Certain lawmen became legendary precisely because their horsemanship skills enabled extraordinary feats of justice in challenging circumstances. Figures like Bass Reeves, a formerly enslaved man who became one of the most successful Deputy U.S. Marshals throughout history were known for their exceptional relationship with their horses, using this partnership to track and capture hundreds of fugitives across Indian Territory. The mounted lawman archetype embodied in these historical figures evolved into a potent cultural symbol that influenced how Americans understood justice on the frontier, emphasizing independence, persistence, and the personal administration of law. Contemporary accounts frequently focused on the quality of the horses these famous lawmen rode, understanding that their success was inextricably linked to their mounts’ capabilities. The legacy of these partnerships between exceptional horses and determined lawmen continues to shape American cultural understanding of justice, emphasizing direct action and persistence against overwhelming odds.

The Decline of Equine Justice and Modern Transitions

The arrival of automobiles, expanded rail networks, and telephone communications gradually diminished the horse’s central role in western justice systems between 1890-1920. This technological transition fundamentally altered how justice was administered, removing the natural limitations of equine transportation and creating a more centralized, less personalized system of law enforcement. Some remote western jurisdictions maintained mounted patrols well into the mid-20th century, particularly in regions where terrain made mechanical transportation impractical or unreliable. The cultural attachment to mounted justice remained strong even as practical necessity faded, with mounted police units maintained in many western communities as ceremonial connections to frontier traditions. Modern specialized mounted units in wilderness areas, border regions, and crowd control situations represent the evolutionary descendants of frontier justice horses, maintaining selected functions where equine capabilities still offer advantages over mechanical alternatives.

conclusion

The horse’s role in Old Western justice extended far beyond simple transportation. These animals were integral partners in a frontier legal system that operated under unique constraints and reflected distinct cultural values. Their strength, speed, and intelligence enabled the extension of law across vast territories where justice might otherwise have remained an abstract concept rather than a practical reality. The partnership between horses and those who sought to establish order in the American West created enduring archetypes that continue to influence our understanding of justice, community responsibility, and the complex moral landscape of frontier society. As we look back on this era, the hoofprints of these justice horses reveal a system that was imperfect and often harsh, but that fundamentally relied on the remarkable bond between humans and horses to function in a challenging environment where justice was as much about practical reach as it was about legal principle.