When European ships crossed the Atlantic to establish new colonies in the Americas, they carried more than just human passengers. Among their most transformative cargo were horses—animals that would reshape the landscapes, economies, and cultures of the New World in profound ways. The reintroduction of horses to the Americas (after their prehistoric extinction) sparked one of history’s most remarkable ecological and cultural revolutions. These majestic animals became essential partners in colonial expansion, transforming transportation, agriculture, warfare, and trade across varied terrains, from the Canadian frontier to the Argentinian pampas. The story of colonial horses is not merely about animal husbandry or transportation—it’s about how a single species became interwoven with the very fabric of emerging American societies, shaping both colonial powers and Indigenous communities in ways that continue to resonate today.

The Return of Horses to the Americas

Though horses originally evolved in the Americas, they became extinct in the Western Hemisphere approximately 10,000 years ago during the Pleistocene extinction. Their reintroduction began with Columbus’s second voyage in 1493, when Spanish ships brought the first horses to the Caribbean islands. These early equine pioneers were primarily Andalusian, Barb, and Arabian breeds—chosen for their hardiness and adaptability to challenging conditions. The significance of this ecological reintroduction cannot be overstated, as it marked not merely the addition of a new species, but the return of a keystone organism that would reshape both ecosystems and human societies. Throughout the 16th century, subsequent expeditions brought more horses to different parts of the Americas, establishing breeding populations that eventually spread across two continents.

Spanish Horses and the Conquest of Central and South America

For Spanish conquistadors, horses offered a powerful military advantage that proved crucial in their conquest of vast indigenous empires. The psychological impact of mounted soldiers on the Aztec and Inca populations—who had never seen such animals—gave the Spanish a temporary but decisive edge. Bernal Díaz del Castillo recorded how Moctezuma’s emissaries reported in terror that the strange beasts “devoured” people, a misunderstanding likely sparked by the sight of horses grinding their bits. Beyond this psychological shock, horses gave Spanish soldiers superior mobility, elevation, and striking power in combat, enabling small groups of conquistadors to overcome much larger indigenous forces. The mounted charge became a devastating tactic, one for which native warriors initially had few effective defenses, fundamentally shifting the military balance of power in the Americas.

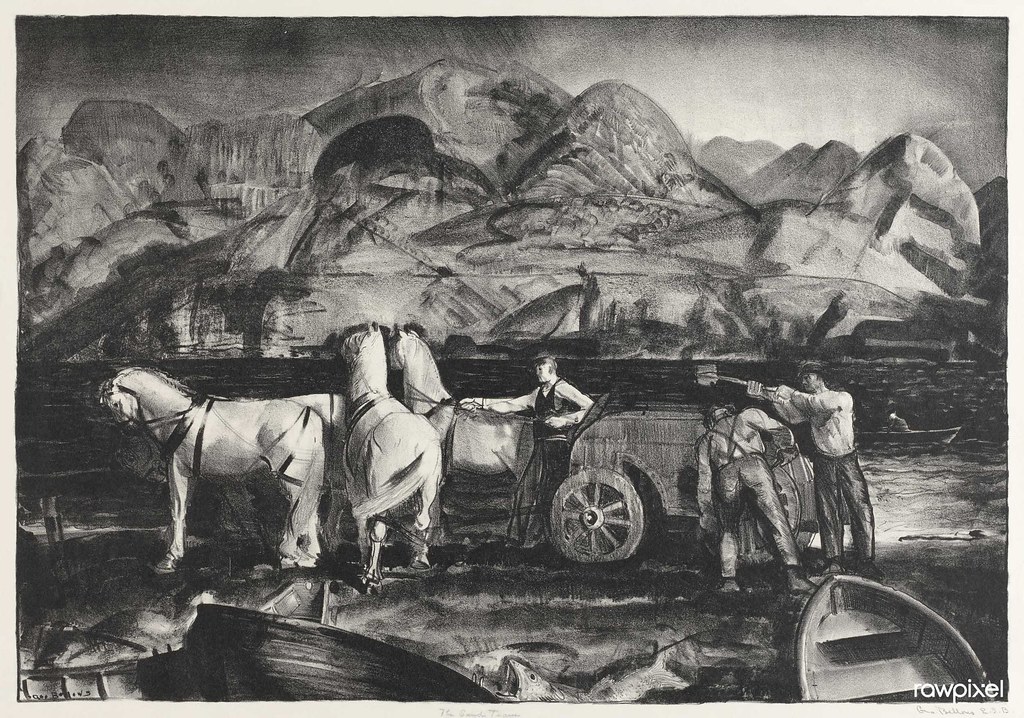

The Foundation of Ranching Culture in the Americas

As Spanish colonization expanded, horses enabled the growth of extensive cattle ranching operations that became central to colonial economies. The vast grasslands of regions like the Argentine pampas, the llanos of Venezuela and Colombia, and later the plains of North America proved ideal for both horse breeding and cattle grazing. Spanish colonial authorities established haciendas, large agricultural estates that relied heavily on horses for managing livestock. The vaquero tradition emerged in this setting, developing specialized techniques for mounted cattle handling that would later influence cowboy cultures across the Americas. These ranching operations not only produced valuable commodities like hides, tallow, and meat, but also fostered distinctive cultural identities centered around horsemanship—traditions that persist in rural communities from Texas to Patagonia.

How Indigenous Peoples Adopted and Transformed Horse Culture

Perhaps the most remarkable chapter in the colonial horse story is how rapidly and thoroughly many Indigenous peoples incorporated horses into their cultures. Through trade and the capture of feral animals, horses spread beyond colonial settlements and transformed Native American societies, particularly among Plains tribes like the Comanche, Lakota, and Blackfoot. These groups developed their own distinctive riding techniques, breeding practices, and cultural associations with horses that often surpassed those of European settlers in sophistication. For many tribes, horses revolutionized hunting practices, with mounted bison hunts replacing earlier methods and dramatically increasing hunting range and productivity. Beyond practical applications, horses became deeply embedded in spiritual practices, social organization, and systems of wealth, fundamentally reshaping Indigenous identities in ways that transcended mere transportation.

Transportation Revolution in Colonial Settlements

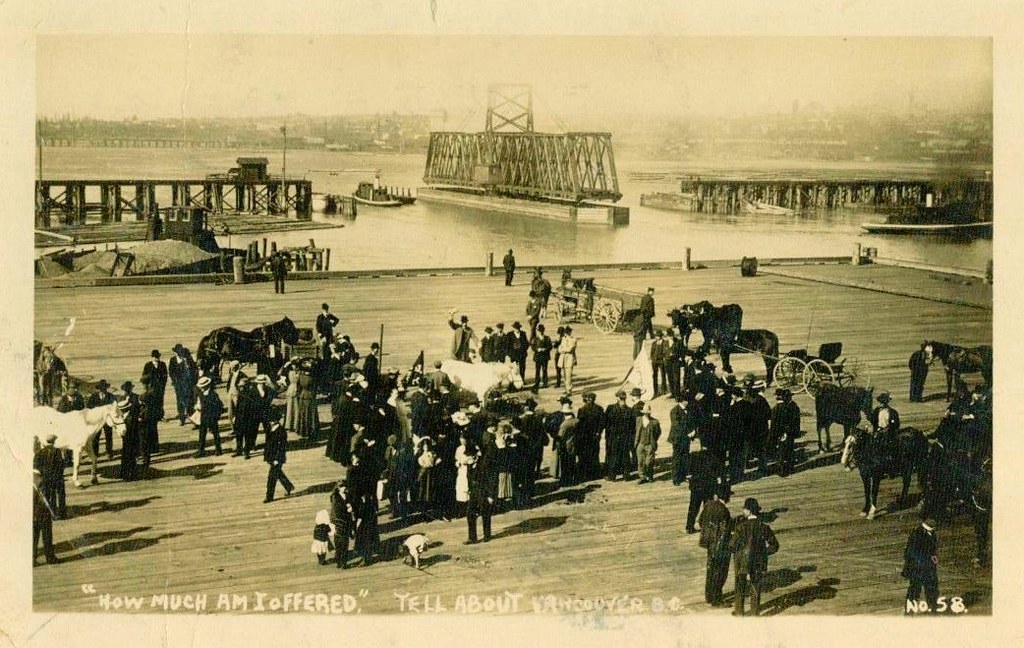

Within established colonial settlements, horses dramatically transformed transportation capabilities and economic possibilities. The ability to move people and goods over long distances with greater speed and greater load capacity than human porters enabled more extensive trade networks connecting coastal ports with interior settlements. Colonial authorities established formal postal systems using horse relay stations, accelerating communication across vast territories and strengthening administrative control. Urban centers developed with horses as a central consideration, with streets designed to accommodate equine traffic and various support facilities such as stables, blacksmith shops, and watering troughs integrated into town planning. The horse-drawn carriage became an essential technology that promoted economic growth while also serving as a potent status symbol for colonial elites, with carriage type and horse quality signaling social position.

Military Applications and Colonial Defense

Beyond the initial conquest period, horses remained crucial to colonial military operations throughout the Americas. Colonial powers established cavalry units that became essential for both external defense and internal control, with mounted soldiers able to respond rapidly to threats across dispersed settlements. The racial and class dynamics of colonial societies were reflected in military horse usage, with European officers and elites typically having access to superior mounts compared to indigenous or mixed-race soldiers. Frontier forts and presidios maintained large horse herds as a military necessity, creating constant demand for pasturage, feed crops, and specialized personnel such as farriers and horse trainers. The vulnerability of military horse herds made them prime targets during conflicts between colonial powers or with indigenous resistance, with horse theft often becoming a strategic act rather than merely a property crime.

Agricultural Applications and Farming Efficiency

While oxen often handled the heaviest agricultural tasks, horses dramatically improved farming efficiency across diverse colonial settings. The introduction of horse-drawn plows allowed for more extensive and rapid field preparation than human-powered methods, expanding the acreage that individual farmers could cultivate. Horses also provided essential power for tasks like threshing grain, pressing apples for cider, and operating primitive grinding mills, serving as living engines in the pre-industrial colonial economy. Transporting harvested crops to market became more efficient with horse-drawn wagons, increasing the economic viability of commercial agriculture beyond mere subsistence farming. In more established colonies, selective breeding produced work horses adapted to various agricultural needs, with heavier draft breeds imported from Europe to supplement the lighter Spanish stock that initially dominated in the Americas.

Feral Horse Populations and Their Ecological Impact

One of the most significant unintended consequences of the horse’s introduction was the establishment of feral populations throughout the Americas. Horses that escaped or were released from Spanish settlements multiplied rapidly in hospitable environments, particularly in grassland regions like the Great Plains and the pampas. These feral herds—known as mustangs in North America and cimarrones in Spanish territories—became a self-perpetuating resource that both indigenous peoples and colonists utilized through capture and domestication. The ecological impact of these new large herbivores was profound, altering grassland composition, seed dispersal patterns, and competition with native grazers like bison. Colonial authorities often held ambivalent views of feral horses, seeing them as valuable resources, potential competitors to domestic stock, and symbols of untamed nature that needed to be controlled.

Horse Trade and Economic Networks

Horses themselves became valuable trade commodities, creating new economic networks that connected disparate regions and cultures. Colonial ports established specialized facilities for transporting horses from Europe and between American colonies, with some regions gaining reputations for producing particularly desirable animals for specific purposes. Indigenous trading networks expanded to include horses, with tribes that had greater access to feral herds often trading animals to groups farther from the source. The complementary goods required for horse management—saddles, bridles, horseshoes, and specialized textiles—created secondary economic opportunities and skilled trades within colonial settlements. By the 18th century, horse fairs had become important economic and social events in many colonial regions, serving as venues for commerce while also reinforcing the cultural centrality of horsemanship.

Horses in British North American Colonies

While Spanish colonies established the first significant horse populations in the Americas, British North American settlements developed their own distinctive equine traditions. The early English colonies initially imported horses primarily from England, with breeds like the Thoroughbred becoming particularly important for establishing elite racing cultures in places like Virginia. Agricultural use dominated in New England and the mid-Atlantic colonies, where farmers bred animals suited to the shorter growing seasons and terrain that differed from southern or Spanish territories. Urban horse use became increasingly sophisticated in cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, with public transportation systems relying on horses emerging by the late colonial period. The unequal access to horses between wealthier coastal settlements and frontier regions contributed to distinctive regional horse cultures that continued to evolve after independence.

Breeding Practices and the Development of American Horse Breeds

The distinct environments and practical needs of colonial settlements eventually led to the development of uniquely American horse breeds. Spanish colonial influence laid the foundation for breeds like the Quarter Horse, known for its exceptional speed over short distances and its utility in cattle work. In the eastern British colonies, crosses between imported English Thoroughbreds and colonial workhorses produced the Narragansett Pacer, a now-extinct breed once prized for its comfortable riding gait on rough colonial roads. Environmental pressures naturally selected for hardiness, disease resistance, and adaptability to local conditions, creating regional horse types better suited to American environments than their European ancestors. Colonial horse breeding initially occurred with minimal record-keeping or formal organizations, but by the late 18th century, more systematic approaches had emerged among elite breeders, particularly for racing stock.

Social Stratification and Horses as Status Symbols

Throughout colonial societies, horses functioned as powerful markers of social status and class identity. The quality, number, and type of horses an individual owned provided visible evidence of their economic standing and social aspirations. Colonial elites invested in imported breeding stock, elegant carriages, and specialized riding equipment to display their wealth and reinforce social boundaries. Access to horses was often stratified along racial lines, with legal restrictions in many colonies limiting ownership or riding privileges for enslaved individuals and, in some cases, free people of color. Even the architecture of colonial settlements reflected this equine-based social stratification, with the homes of wealthy colonists featuring elaborate stables and carriage houses designed to showcase their valuable horses. Public events centered around horsemanship—particularly racing and formal hunts—became important venues for elite social performance and networking.

The Enduring Legacy of Colonial Horse Culture

The equine foundations established during the colonial period created cultural patterns and economic relationships that endured long after independence movements transformed the political landscape of the Americas. National identities in countries like Mexico, Argentina, and the United States incorporated elements of horse culture as symbols of heritage and character, often romanticizing the horseman as embodying essential national virtues. Regional horse traditions that developed during the colonial era—from the gaucho culture of Argentina to the vaquero traditions of Mexico and the western United States—evolved into cultural institutions that remain significant today. Even as industrialization and motorization gradually displaced horses from their economic centrality, the symbolic and recreational significance of horsemanship maintained a powerful cultural presence rooted in these colonial foundations. The living legacy of colonial horse culture can still be seen in everything from the continued popularity of rodeo sports to the wild horse herds that remain direct descendants of colonial equines, connecting modern Americans to this transformative chapter of ecological and cultural history.

The reintroduction of horses to the Americas stands as one of history’s most consequential ecological exchanges, fundamentally altering the trajectory of human societies across two continents. From conquistadors’ mounts to indigenous war ponies, from humble farm workers to symbols of colonial elegance, horses played countless roles in shaping the Americas. Their integration into diverse societies created not only practical advantages but also profound cultural transformations that continue to influence national identities, regional traditions, and human-animal relationships to this day. As we reflect on the colonial period, understanding the central role horses played provides essential insight into how a single species became so deeply interwoven with human experience across remarkably different contexts—serving simultaneously as tools of conquest and vehicles of indigenous resilience, as engines of economic development and living symbols of freedom.