Throughout history, the relationship between rulers and their horses has been one of profound significance. These noble animals weren’t merely transportation—they were symbols of power, extensions of imperial identity, and sometimes even beloved companions. From the cobbled streets of Rome to the vast steppes of China, emperors rode upon specially selected steeds that carried not just their physical weight but the symbolic weight of entire civilizations. These imperial mounts were often as celebrated as their riders, immortalized in art, literature, and legend. Their bloodlines were meticulously documented, their training exquisitely refined, and their equipment crafted with the finest materials available. This exploration of imperial horses takes us across continents and millennia, revealing how these magnificent animals shaped history and reflected the values of the civilizations they served.

Bucephalus: Alexander the Great’s Legendary Companion

Though Alexander ruled before the formal Roman Empire, his famous steed Bucephalus set the standard for the imperial war horse. According to Plutarch, the young Alexander tamed the supposedly unrideable black stallion by noting that it was afraid of its own shadow. Bucephalus carried Alexander through numerous campaigns across three continents, forming a partnership that became legendary throughout the ancient world. When Bucephalus died in 326 BCE after the Battle of the Hydaspes in present-day Pakistan, Alexander founded an entire city in his honor—Bucephala. This horse-rider relationship established a tradition that would influence how future emperors regarded their equine companions, elevating the imperial mount from mere beast of burden to historical participant.

Roman Equestrian Tradition and Imperial Mounts

The Roman Empire’s relationship with horses was fundamentally shaped by its military needs and class structure. The equites, or equestrian class, derived both their name and status from their ability to provide a horse for military service. Roman emperors typically favored horses from Cappadocia (in modern Turkey) and Spain, prizing them for their speed, endurance, and impressive stature. Julius Caesar reportedly rode a remarkable horse with feet that resembled human hands, a detail mentioned by both Suetonius and Pliny the Elder. Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, established imperial stables that set standards for breeding that would influence European horsemanship for centuries. The Romans developed sophisticated veterinary practices specifically for their valuable horses, including treatments documented in Vegetius’s “Mulomedicina,” reflecting the critical importance of these animals to imperial power.

Imperial Mounts in Byzantine Splendor

As the Roman Empire transformed into the Byzantine Empire, horses became even more heavily laden with imperial symbolism. Emperor Justinian I is immortalized in the famous equestrian statue at the Augustaeum in Constantinople, demonstrating how the mounted ruler became a central icon of imperial authority. Byzantine emperors rode white horses in ceremonial processions, the animals draped in gold-embroidered silk with jewel-encrusted bridles and saddles. The imperial stables housed horses specifically bred for imperial ceremonial functions, separate from war horses or racing steeds. The Hippodrome of Constantinople became not just a racing venue but a political space where the emperor displayed his connection to these powerful animals before his subjects. Byzantine horse equipment reflected extraordinary craftsmanship, with surviving examples showing intricate cloisonné enamel work and religious imagery that connected imperial authority to divine approval.

Charlemagne and the European War Horse Tradition

Charlemagne, crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 CE, revolutionized European cavalry by promoting the breeding of larger, stronger horses capable of carrying armored knights. His personal mount was reportedly named Tencendur, a powerful destrier that carried him through numerous campaigns. Charlemagne established imperial stud farms and issued capitularies (royal decrees) regulating horse breeding throughout his vast territories. The Carolingian emphasis on heavy cavalry would eventually lead to the development of the medieval destrier, the ultimate war horse of European chivalry. Charlemagne’s horse policies reflected his broader imperial vision—creating standardized systems across diverse territories and reviving elements of Roman imperial tradition while adapting them to new military realities.

The Han Dynasty’s “Celestial Horses”

On the eastern end of the Eurasian continent, Chinese emperors developed their own profound relationships with imperial horses. Emperor Wu of Han (reigned 141-87 BCE) was so determined to acquire the superior “blood-sweating” horses of Ferghana (in modern Central Asia) that he launched military campaigns to secure them. These “celestial horses” or “heavenly horses” were believed to be descended from dragons and capable of carrying their riders to immortality. The emperor’s fascination with these horses was immortalized in poetry and art, including the famous flying horse bronze from the Eastern Han period. Imperial Chinese records show that these prized Central Asian horses were kept in special stables and fed specialized diets including honey and wine. The Han emperors established a complex system of horse breeding and management, with different types of horses designated for different imperial functions.

The Tang Dynasty’s Equestrian Excellence

The Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) represented the golden age of horsemanship in imperial China, with emperors personally leading hunting expeditions and military campaigns on carefully selected mounts. Emperor Xuanzong maintained thousands of horses in the imperial stables, with the finest reserved for his personal use. The Tang court’s enthusiasm for horses influenced Chinese art, with tomb figurines and paintings depicting elegant horses in dynamic poses. Emperor Taizong’s (reigned 626-649 CE) war horse Autumn Dew was so beloved that the emperor commissioned a relief sculpture of the animal that was placed at his tomb. The imperial passion for horses during this period coincided with increased contact with Central Asian cultures through the Silk Road, bringing new bloodlines and horsemanship techniques to China.

Mongolian Horse Culture and Kublai Khan

When Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty in China (1271-1368), he brought with him the Mongol tradition of horse culture that had enabled his grandfather Genghis Khan to build the largest contiguous land empire in history. The Khan maintained a personal herd of white horses for ceremonial purposes, a tradition with deep significance in Mongol culture. Marco Polo described the emperor’s summer palace at Xanadu as having stables for 10,000 pure white horses, whose milk was reserved for the imperial family and highest nobility. Unlike many settled emperors, Kublai Khan and his predecessors had a functional rather than purely ceremonial relationship with horses, having been raised riding from early childhood. The Mongol imperial tradition viewed horses not just as symbols but as the fundamental foundation of power, with horse management remaining central to state policy even after the establishment of a more sedentary court.

The Ottoman Sultans’ Arabian Treasures

The Ottoman Empire bridged East and West, and its rulers combined Turkish horse traditions with Arabian bloodlines to create exceptional imperial mounts. Sultan Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople, rode a white Arabian stallion into the conquered city in 1453, establishing a tradition that subsequent sultans would follow. Ottoman imperial stables were organized with military precision, with special sections dedicated to horses of specific colors and types for different ceremonial functions. The empire maintained specialized stud farms in Anatolia and the Balkans to supply the sultan’s stables with the finest specimens. Ottoman imperial horses were adorned with spectacular caparisons for parades, featuring gold thread embroidery, pearls, and precious stones, examples of which can still be seen in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul.

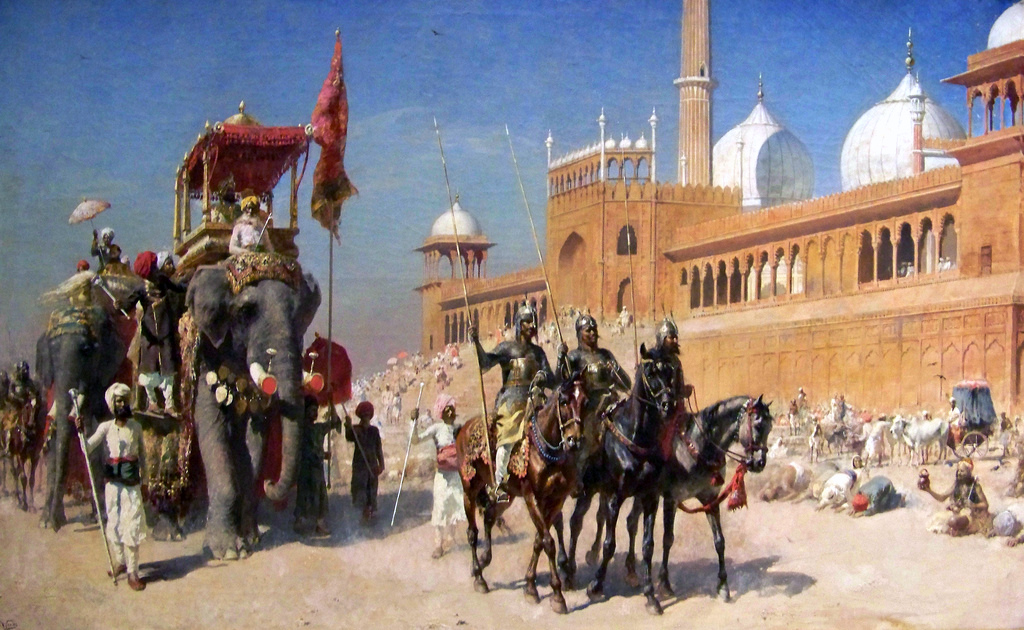

The Mughal Emperors and Their Equine Passions

The Mughal emperors of India combined their Turkic-Mongol heritage with Persian cultural influences, resulting in a sophisticated appreciation for fine horses. Emperor Akbar (reigned 1556-1605) maintained stables of over 12,000 horses and developed a classification system with seven ranks based on the animals’ qualities and characteristics. Mughal imperial horses came from diverse regions including Arabia, Persia, and Central Asia, with detailed records kept of their pedigrees, training, and feeding regimens. The emperor Jahangir was particularly fond of his Persian horses and had them portrayed by court artists in detailed miniature paintings that survive today. The Ain-i-Akbari, a detailed administrative document from Akbar’s reign, devotes entire sections to the imperial horse establishment, demonstrating how central these animals were to Mughal governance and self-presentation.

The Sacred White Horses of Japan’s Emperors

In Japan, white horses held particular significance in Shinto religion and were presented as offerings at important shrines associated with the imperial family. The Japanese imperial household maintained sacred white horses that participated in religious ceremonies and processions, connecting the emperor’s authority to divine approval. Unlike the war horses of many other imperial traditions, these animals served primarily ritual rather than military functions. Historical records indicate that foreign horses, particularly from Korea and later Mongolia, were highly valued gifts to the Japanese imperial court. The imperial stable tradition continues today, with sacred white horses still maintained for Shinto ceremonial purposes at shrines like Ise Jingū, Japan’s most sacred Shinto site.

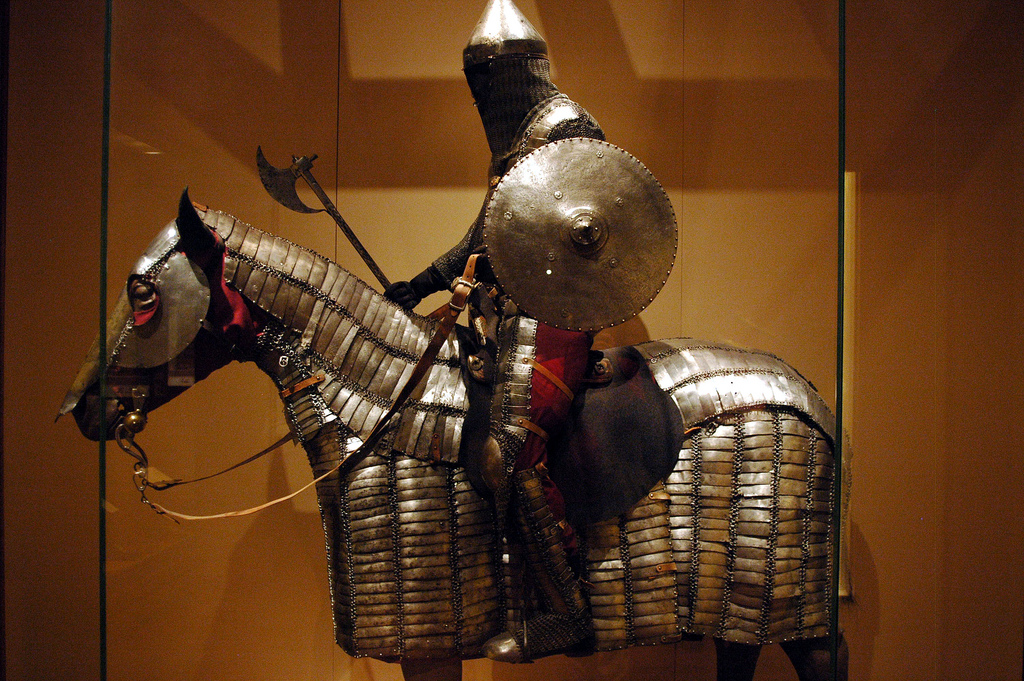

Imperial Horse Equipment and Symbolism

The equipment used on imperial horses constituted some of the most exquisite craftsmanship of their respective civilizations. Roman imperial saddles featured ivory and gold inlay, while Chinese emperors used saddles decorated with jade and silk embroidery. In many traditions, the color of the horse conveyed specific meanings—white horses symbolized purity and divine connection across cultures from Rome to Japan. The height of the horse physically elevated the emperor above his subjects, a spatial representation of hierarchy that was universally understood. The quality and ornamentation of equestrian equipment served as mobile displays of imperial wealth and artistic achievement, with techniques like Byzantine enamelwork or Ottoman gold embroidery reaching their highest expression in imperial horse gear.

The Decline of Imperial Horse Culture

The relationship between emperors and their horses began to change with the introduction of firearms and later mechanization. The Qing emperors of China continued traditional Manchu horse culture into the early 20th century, but with increasingly ceremonial rather than practical significance. European monarchies gradually transformed their horse traditions into largely ceremonial functions like the British Royal Horse Guards or the Spanish Royal Andalusian School. Japan’s Meiji Emperor adopted Western-style military uniforms and equestrian practices as part of modernization, signaling a fundamental shift in imperial self-presentation. The last mounted emperors—including Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and Mohammed Zahir Shah of Afghanistan—maintained traditions into the mid-20th century before modern transportation and warfare rendered imperial horsemanship primarily symbolic rather than functional.

Legacy and Continuing Traditions

Though few ruling monarchs today regularly ride horses in an official capacity, equestrian traditions remain important symbolic connections to imperial heritage. The British Royal Family maintains strong equestrian traditions, with ceremonial mounted units performing at events like Trooping the Colour. In Morocco, mounted royal guards continue a tradition dating back centuries, using horses descended from the same Barb bloodlines that served previous sultans. Modern archaeological techniques are providing new insights into ancient imperial horse cultures, with DNA analysis of horse remains from royal tombs revealing breeding patterns and movement of bloodlines across continents. Museums worldwide display spectacular imperial horse equipment, from the gilt bronze saddles of Chinese emperors to the jewel-encrusted bridles of Ottoman sultans, testifying to the historical importance of these imperial partnerships between humans and horses.

From Bucephalus to the last mounted emperors of the modern era, imperial horses carried not just their royal riders but the weight of tradition, symbolism, and power. These animals represented the intersection of practical necessity and extravagant display, of military might and ceremonial splendor. They connected rulers to divine authority, to military success, and to the land itself. The special relationships between emperors and their horses reveal how these magnificent animals became extensions of imperial identity—living symbols that embodied the values and aspirations of entire civilizations. Though technology has largely replaced the practical function of imperial mounts, their cultural and historical significance continues to capture our imagination, reminding us of a time when the fate of empires could rest on the strength, speed, and spirit of these remarkable animals.