In the mechanized horror of the First World War, amid the thunder of artillery and the emerging roar of tanks, millions of animals served alongside soldiers in one of history’s most devastating conflicts. Among these animal conscripts, horses stand as perhaps the most numerous and consequential contributors to the war effort. Between 1914 and 1918, an estimated eight million horses perished while serving the armies of all nations involved—a staggering sacrifice largely overlooked in many historical accounts. These loyal animals transported troops, hauled artillery, delivered supplies through impossible terrain, and charged into battle despite deafening explosions and caustic gas. Their story represents one of the last and largest deployments of animals in modern warfare, a bittersweet chapter where the ancient bond between humans and horses met the grim realities of industrial combat. This article explores the remarkable contribution of these four-legged warriors, whose silent service helped shape the outcome of the Great War.

The Unprecedented Scale of Equine Mobilization

When war erupted in 1914, military strategists across Europe rapidly recognized their critical need for horses despite the technological advancements of the early 20th century. Britain alone sent more than one million horses and mules to various battlefronts, sourcing them from farms, racetracks, and even purchasing hundreds of thousands from the United States and Canada. The German army deployed approximately 1.4 million horses by the war’s midpoint, while France relied on nearly a million of these animals to support their military operations. This massive mobilization of equines represented the largest movement and deployment of horses in human history, with animals gathered from across continents to serve in the muddy trenches and battlefields of Europe. The sheer logistical challenge of transporting, housing, feeding, and maintaining these animals under wartime conditions remains an underappreciated feat of military organization.

Artillery Horses: Muscle Behind the Guns

Perhaps no role better exemplified the essential nature of horses than their service in artillery units, where their raw strength made possible the movement of increasingly heavy weaponry. A single 13-pounder field gun required a team of six horses to maneuver it into position, while heavier howitzers needed teams of up to twelve horses struggling in tandem through mud that could reach their bellies. These horse teams operated under constant threat, as enemy forces recognized artillery positions as prime targets for counter-battery fire. Statistical analyses suggest that horses serving in artillery units suffered among the highest casualty rates, with many teams being replaced multiple times throughout the conflict. Their crucial contribution allowed for the tactical mobility of artillery pieces that would otherwise have remained stranded, particularly on the Western Front where motorized vehicles frequently became immobilized in the cratered, waterlogged terrain.

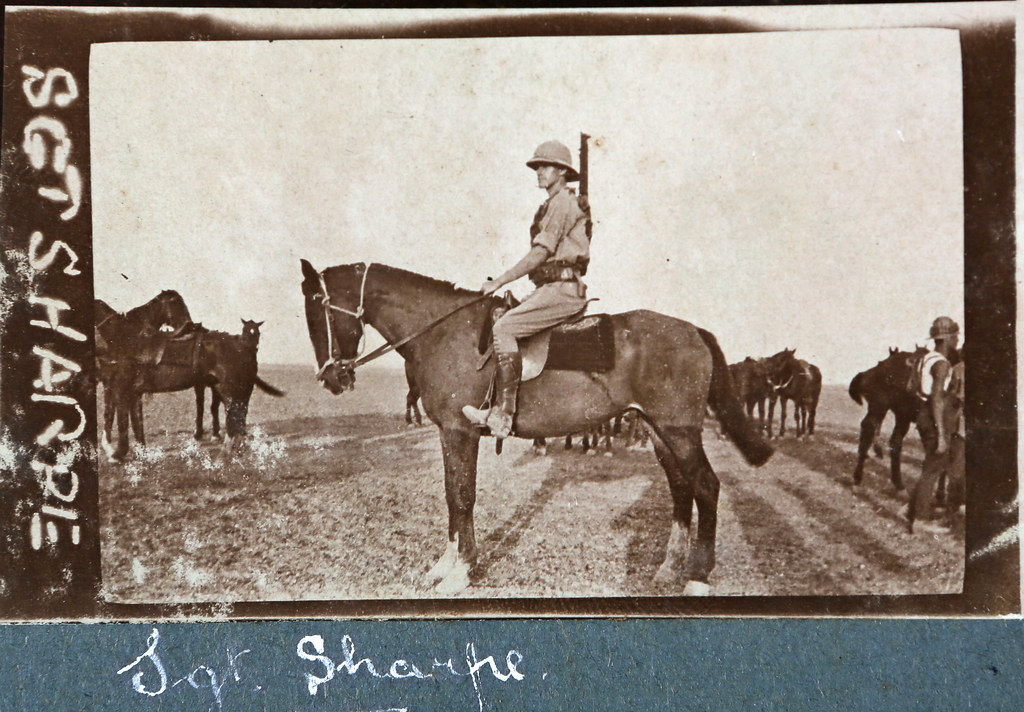

Cavalry’s Evolving Role

The Great War marked a profound transition in cavalry warfare, as mounted units discovered their traditional battlefield role diminished by modern weaponry. When war began, all major powers deployed substantial cavalry forces, with romantic notions of horseback charges deciding battles as they had for centuries. The reality proved brutally different, as machine guns, artillery barrages, and barbed wire made traditional cavalry charges suicidal on the Western Front. Despite this tactical obsolescence in direct combat, cavalry units adapted to new roles including reconnaissance, screening operations, and rapid exploitation of breakthroughs. On the Eastern and Middle Eastern fronts, where fighting remained more mobile across vast distances, cavalry retained greater battlefield relevance throughout the conflict. The Australian Light Horse Brigade’s famous charge at Beersheba in 1917 stands as one of the war’s few successful traditional cavalry actions, though the Australians dismounted before reaching Turkish trenches, effectively using horses for rapid deployment rather than direct combat.

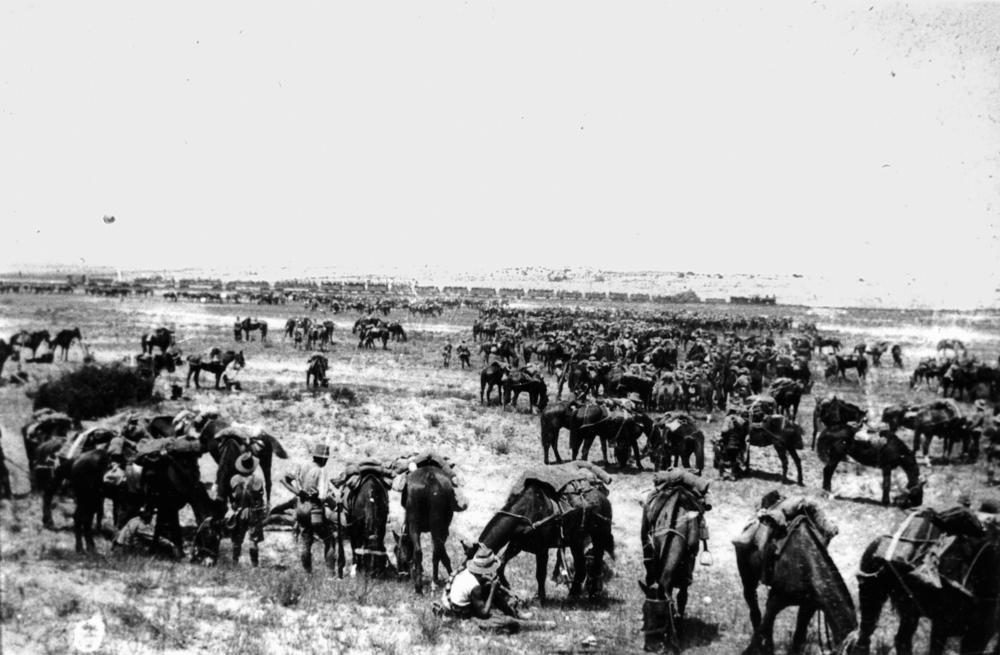

The Supply Chain Champions

The most numerous yet often least recognized equine contribution came from the countless draft horses and mules that formed the backbone of military logistics. These sturdy animals transported ammunition, food, water, medical supplies, and construction materials to frontline positions where motorized vehicles couldn’t operate due to destroyed roads or nonexistent infrastructure. A single division required approximately 5,000 horses to maintain its supply lines, with each animal capable of carrying up to 175 pounds of equipment in addition to their rider. The British Army’s Army Service Corps alone utilized over 300,000 horses and mules for transport duties, creating a living supply chain that stretched from coastal ports to the frontline trenches. When weather conditions deteriorated, as they frequently did in the infamous mud of Flanders, these animal transport columns often provided the only reliable means of delivering crucial supplies to soldiers in forward positions.

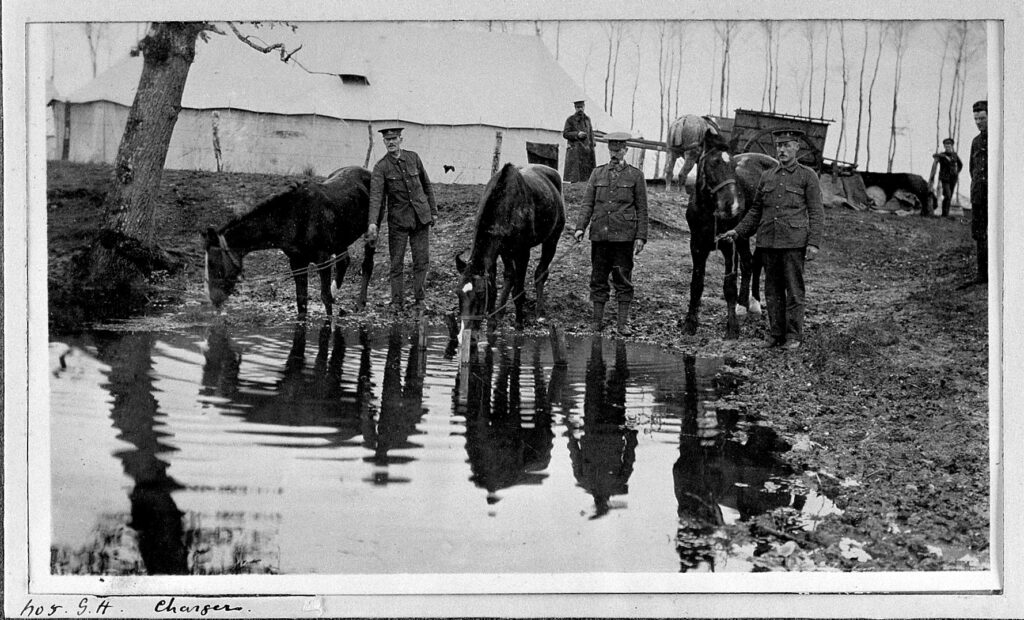

Veterinary Medicine’s Wartime Evolution

The unprecedented deployment of horses in World War I catalyzed remarkable advancements in veterinary medicine that would benefit animals long after the conflict ended. The British Army Veterinary Corps expanded from 364 personnel at the war’s outset to over 28,000 by 1918, developing new treatments for wounds, respiratory conditions, and exhaustion. Field veterinary hospitals became increasingly sophisticated, with specialized facilities for different conditions and mobile veterinary units designed to provide immediate care near the frontlines. Veterinarians pioneered new surgical techniques, anesthetic approaches, and preventative medicine protocols that saved hundreds of thousands of animals that would have perished in previous conflicts. The statistical improvement in equine survival rates throughout the war tells a compelling story—by 1918, the British army had reduced monthly horse mortality from disease and exhaustion from 3% to less than 0.5%, representing one of the war’s few positive humanitarian developments.

The Physical and Psychological Toll

Horses serving in World War I endured physical hardships that pushed many beyond their biological limits, suffering conditions that mirrored the miseries of the human soldiers alongside them. Respiratory ailments became endemic as horses inhaled the same toxic chemical gases deployed against human troops, with many animals developing chronic breathing difficulties that persisted long after exposure. Skin conditions proliferated in the damp, vermin-infested stables hastily constructed near the front, while nutritional deficiencies emerged as quality feed became increasingly scarce. Many horses worked to complete exhaustion, pulling heavy loads through deep mud for 20 or more hours without rest, particularly during major offensives when the demand for supplies and ammunition increased dramatically. Perhaps most poignant were the psychological effects observed in many war horses, with veterinary records documenting cases of animals exhibiting symptoms reminiscent of what would later be recognized as combat stress reactions in humans—trembling, refusal to work, and extreme startle responses to loud noises.

The Remount Service and the Global Horse Trade

The staggering casualties among war horses necessitated an enormous replacement system that transformed the global horse trade into a military supply operation of unprecedented scale. Britain’s Remount Department purchased over 460,000 horses from the United States alone, with specialized “horse ships” crossing the Atlantic despite the grave threat of German submarine attacks. Canada contributed approximately 130,000 horses to the Allied cause, while Australia and New Zealand supplied tens of thousands more, particularly for operations in the Middle East. The quality control measures implemented by remount officers became increasingly sophisticated, with detailed specifications regarding age, height, weight, and conformation depending on the intended military role. Specialized remount depots were established throughout Britain and France, where newly arrived horses underwent a conditioning program before assignment to military units. The global nature of this equine procurement effort reflected the war’s industrialized approach to resource management, with horses viewed simultaneously as irreplaceable military assets and ultimately expendable resources.

Famous War Horses and Their Stories

Among the millions of equine participants in World War I, certain individual horses achieved recognition for exceptional service or compelling narratives that captured public imagination. Warrior, the mount of General Jack Seely, survived four years on the Western Front despite being present at major battles including Ypres and the Somme, later earning the title “the horse the Germans couldn’t kill” in British newspapers. The Australian horse Sandy accompanied Major General Sir William Bridges to Gallipoli, and after Bridges’ death became the only horse among 136,000 Australian horses sent overseas to return to Australia after the war. In Germany, the famous military horse Parcival carried Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg on ceremonial occasions and became a national symbol, while the American horse Sergeant Reckless gained posthumous fame for her exploits during the Korean War but represented a tradition of equine military service that began during World War I. These individual stories humanized the broader equine contribution, helping civilians comprehend the animals’ significance to the war effort.

Artistic and Literary Commemoration

The profound impact of horses on the First World War resonated deeply within the artistic and literary consciousness of the era, producing works that continue to shape our understanding of these animals’ contributions. War artists like Alfred Munnings created powerful paintings depicting horses in various military roles, with his wartime commissions forming a valuable historical record of equine service on multiple fronts. The poet Siegfried Sassoon, himself a cavalry officer, wrote movingly about horses in poems like “The Dug-Out” and “Dreamers,” capturing both their suffering and their bond with human soldiers. Perhaps most famously, Michael Morpurgo’s novel “War Horse,” later adapted into a successful stage play and film, introduced new generations to the experience of horses in the Great War through the fictional journey of Joey, a farm horse conscripted into military service. These artistic interpretations helped preserve the memory of war horses when official historical accounts often overlooked their contribution, creating an emotional connection that purely factual accounts might have failed to establish.

The Tragic Aftermath and Disposal

The conclusion of hostilities in November 1918 raised difficult questions about the fate of surviving military horses that revealed the often-unsentimental attitude toward these animal veterans. Financial and logistical constraints made repatriation impractical for most animals, with the cost of shipping a horse home often exceeding the animal’s market value. Of the approximately 136,000 Australian horses sent overseas, only one (the aforementioned Sandy) returned to Australia, with the remainder sold to local farmers, other armies, or slaughterhouses. British policy classified horses as military equipment to be disposed of as efficiently as possible, with about 60,000 sold for agricultural work in France and Belgium, while thousands more were slaughtered for meat. The unceremonious disposal of animals that had served loyally troubled many soldiers, with historical accounts documenting cases where cavalry officers purchased their mounts privately or even euthanized them personally rather than consign them to unknown fates. This callous treatment of equine veterans eventually sparked public outcry and contributed to the founding of several animal welfare organizations dedicated to working horses.

Memorials and Modern Recognition

The sacrifices of war horses have received increasing recognition through memorials and commemorative efforts that acknowledge their crucial wartime contribution. The Animals in War Memorial in London’s Hyde Park, unveiled in 2004, features prominently sculpted horses alongside other animal veterans, with the inscription “They had no choice” poignantly highlighting the involuntary nature of animal service. Australia’s “The Desert Mounted Corps Memorial” at Albany in Western Australia commemorates the horses that served with ANZAC mounted divisions, depicting a mounted soldier with his horse. In the United States, the War Horse Memorial in San Diego pays tribute to the thousands of American horses shipped overseas during the conflict. These physical monuments have been complemented by educational initiatives, museum exhibitions, and documentary films that seek to incorporate the equine experience into mainstream historical understanding of the war. Modern veterinary and equine welfare organizations frequently reference the wartime contribution of horses as part of their heritage, creating a continuous thread of remembrance that extends into contemporary animal care practices.

Legacy and Historical Significance

World War I represents a pivotal moment in the millennia-old relationship between humans and horses—the last major conflict where these animals played an indispensable military role before mechanization rendered them largely obsolete on the battlefield. The war’s aftermath accelerated the transition from horse power to motor power across civilian sectors as well, as millions of surplus military vehicles became available for peacetime conversion. The specialized knowledge developed for horse care during the war transferred to civilian veterinary practice, improving treatment for working animals worldwide. Perhaps most significantly, the visible suffering of horses during the conflict contributed to evolving attitudes regarding animal welfare, with several influential animal protection organizations tracing their founding motivations to the treatment of war horses. The stark contrast between the romanticized pre-war vision of cavalry charges and the grim reality of horses struggling through mud under artillery fire became a powerful metaphor for the war’s broader disillusionment, marking the end of one historical era and the beginning of another.

In the century since the guns of the Western Front fell silent, our understanding of World War I’s complexity continues to evolve. The contribution of horses to this watershed conflict reminds us that history’s currents are shaped not only by human decisions but also by the capacities and limitations of the animals that have shared our journey. As technological warfare has largely eliminated horses from modern battlefields, the eight million equine casualties of World War I stand as silent witnesses to an ancient partnership between species tested in the crucible of industrial warfare. Their legacy lives on not only in memorials of stone and bronze but in our continuing obligation to remember that in the tragedy of war, suffering transcends the boundaries of species. The horse heroes of World War I, pressed into service without choice or understanding, deserve their place in our collective memory of a conflict that transformed the world they helped to shape.