Throughout human history, few animals have captured our imagination, served our needs, and inspired our artistic expression quite like the horse. From the earliest cave paintings to contemporary digital art, horses have maintained a special place in human culture and symbolism. This enduring relationship between humans and equines has been documented across millennia through various artistic mediums, reflecting changing societal values and human-animal relationships. As we trace the evolution of equine depictions in art, we uncover not just the changing styles and techniques of artistic expression, but also profound insights into human civilization itself—our beliefs, our social structures, our technological advances, and our emotional connections to these magnificent creatures.

Prehistoric Equine Art: The First Horse Depictions

The earliest known representations of horses in human art date back approximately 30,000 years to the Upper Paleolithic period, appearing prominently in cave paintings across Europe. The Lascaux and Chauvet caves in France and the Altamira cave in Spain showcase some of the most remarkable prehistoric horse imagery, rendered with surprising anatomical accuracy and dynamic movement. These ancient artists used natural pigments like ochre, hematite, and charcoal to create vivid depictions that have survived millennia. Interestingly, studies suggest these weren’t merely decorative works but likely held significant spiritual or practical importance, perhaps related to hunting rituals or early forms of animism. The predominance of horses in these early artistic endeavors indicates the species’ importance to our ancestors long before domestication.

Ancient Civilizations and the Symbolic Horse

As human societies developed into early civilizations, horses transitioned from being merely hunted animals to symbols of power, wealth, and divine connection. In ancient Egypt, horses were relatively late arrivals but quickly became associated with warfare and pharaonic power, appearing in relief carvings and tomb paintings pulling chariots. Mesopotamian cultures featured horses prominently in their art, particularly in royal hunt scenes and military victories that emphasized the king’s strength and authority. In ancient Persia, horses appeared in elaborate palace friezes symbolizing imperial might, while Greek and Roman art evolved sophisticated equine representations in sculpture, mosaics, and pottery, often portraying mythological scenes featuring centaurs or divine horses like Pegasus. These ancient civilizations established the horse as a multifaceted symbol that would influence artistic traditions for millennia to come.

Medieval Equestrian Imagery and Chivalric Ideals

The medieval period witnessed a significant evolution in horse symbolism as Christianity became the dominant religion across Europe, incorporating equine imagery into its iconography. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse became powerful symbolic figures in religious art, while saints like George and Martin were frequently depicted mounted on horses, emphasizing their nobility and divine mission. Secular art of this period glorified the mounted knight as the embodiment of chivalric ideals, with illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, and sculptures featuring heavily armored warhorses carrying equally armored knights. The Bayeux Tapestry, chronicling the Norman Conquest of England, dedicated considerable space to equestrian imagery, revealing the central role horses played in medieval warfare and aristocratic identity. Throughout this era, the accuracy of horse anatomy often took a backseat to symbolic representation, with artists focusing more on conveying status and moral qualities than realistic equine physiology.

Renaissance Mastery: Anatomical Accuracy and Equestrian Portraits

The Renaissance period marked a revolutionary shift in equine art as artists returned to careful observation of nature and applied new techniques of perspective and anatomical study. Leonardo da Vinci’s studies of horse anatomy and movement demonstrated unprecedented scientific curiosity about equine physiology, influencing generations of artists. Equestrian portraiture emerged as a distinct genre during this period, with works like Donatello’s “Gattamelata” and Verrocchio’s “Colleoni Monument” establishing conventions for depicting powerful leaders astride magnificent steeds. Northern Renaissance artists like Dürer created meticulously detailed engravings of horses that captured both their physical presence and inner vitality. This period also saw the publication of the first treatises on horsemanship, illustrated with detailed images that combined artistic beauty with practical instruction, reflecting the growing sophistication of Renaissance equestrian culture and its artistic expression.

Baroque Grandeur: The Horse as Symbol of Absolute Power

In the Baroque era, equestrian art reached new heights of dramatism and political symbolism, particularly in service to absolute monarchies. Velázquez’s royal equestrian portraits of Philip IV of Spain showcase the horse as an extension of royal power, with controlled movements signifying the king’s control over his realm. The famous equestrian portrait of Louis XIV by Charles Le Brun and the monumental sculptures at Versailles similarly used prancing, powerful horses to amplify the Sun King’s image of divine authority. Peter Paul Rubens brought unprecedented dynamism to equine imagery, with muscular, spirited horses often depicted in violent hunting scenes or battle compositions that emphasized their raw power and emotional expressiveness. The levade, courbette, and capriole—the “airs above ground” of classical dressage—became frequently depicted poses that demonstrated both equine training and human mastery, serving as metaphors for the ideal ordered state under absolute rule.

The Age of Enlightenment: Scientific Documentation and Sport

During the 18th century, the Enlightenment’s emphasis on scientific knowledge transformed equine art into a more systematic documentation of breeds, anatomy, and movement. George Stubbs, perhaps the most influential equine artist of this period, combined artistic genius with scientific investigation, dissecting horses to understand their musculature and skeletal structure before creating his masterpieces. His anatomical text “The Anatomy of the Horse” (1766) revolutionized equine illustration with its precision and detail. This era also saw the rise of sporting art as a major genre, particularly in Britain, where artists like James Seymour and John Wootton specialized in racing scenes and fox hunting compositions that celebrated rural aristocratic pastimes. The portraiture of prized racehorses became increasingly common, reflecting the growing importance of thoroughbred breeding and racing in elite culture. These detailed, naturalistic depictions marked a shift toward celebrating the horse as an athlete and companion rather than merely as a symbol of power.

Romanticism and the Wild Spirit: Horses in 19th Century Art

The Romantic movement of the 19th century embraced the horse as a symbol of untamed nature and emotional freedom, contrasting with the increasingly mechanized industrial world. Eugène Delacroix’s dramatic battle scenes featured horses in poses of extreme anguish or energy, their flowing manes and wild eyes embodying the Romantic fascination with intense emotion and sublime natural power. Théodore Géricault’s iconic “The Raft of the Medusa” included a spectral white horse as a symbol of hope, while his studies of racehorses captured their speed and grace with unprecedented dynamism. In America, the horse became central to the mythology of westward expansion, with artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell creating iconic images of cowboys, Native Americans, and wild mustangs that helped define American national identity. This period also saw growing interest in depicting working horses, reflecting romantic nostalgia for rural life as urbanization accelerated across Europe and North America.

Modernism’s Deconstruction: From Degas to Picasso

The modernist revolution in art profoundly transformed equine representation, beginning with Edgar Degas’s radical rethinking of the racehorse subject. Degas captured horses in unprecedented off-balance moments, using innovative cropping and unusual viewpoints that rejected the traditional heroic equestrian portrait. Post-impressionists like Toulouse-Lautrec brought new psychological insight to images of circus horses and racing subjects, often focusing on the relationship between humans and horses in entertainment contexts. The early 20th century saw even more dramatic experiments, with Franz Marc’s expressionist blue horses representing spiritual yearning through non-naturalistic color, while futurists like Umberto Boccioni used horses to explore concepts of speed and dynamism, breaking down forms into geometric patterns. Perhaps most radically, Pablo Picasso deconstructed and reimagined equine imagery throughout his career, from his rose period circus horses to the agonized equine figures in “Guernica,” using horse symbolism to express both personal and political concerns.

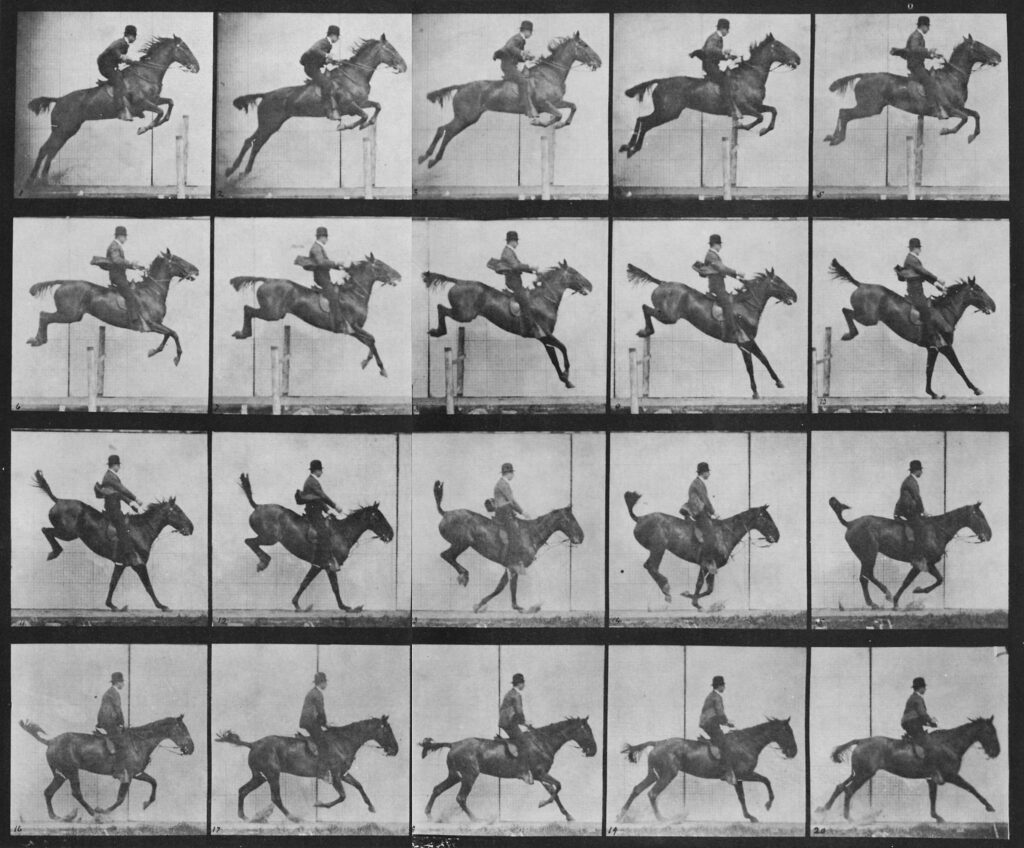

Photographic Revolution: Capturing Equine Movement

The development of photography in the 19th century dramatically influenced how artists understood and depicted horses, beginning with Eadweard Muybridge’s groundbreaking photographic studies of equine locomotion in the 1870s. His sequential photographs definitively settled the long-debated question of whether all four hooves leave the ground during a gallop, forever changing how artists rendered horses in motion. Early 20th-century photographers like Lartigue captured the drama of horse racing with new portable cameras, while others documented the declining role of working horses in increasingly mechanized societies. By mid-century, photographers like Robert Vavra specialized in artistic equine photography that emphasized the horse’s beauty and emotional expressiveness, creating iconic black and white images that influenced both fine art and popular culture. The photographic medium also proved essential for documenting vanishing horse cultures and traditions worldwide, preserving visual records of human-equine relationships that stretched back millennia.

Popular Culture and Commercialization: From Roy Rogers to Ferrari

The 20th century witnessed horses transitioning from working animals to symbols in mass media and commercial branding, reflecting their evolving place in society. Hollywood westerns created iconic imagery of heroic cowboys and their faithful steeds, with stars like Roy Rogers and his palomino Trigger becoming household names across America. Children’s literature and film embraced equine protagonists from “Black Beauty” to “National Velvet,” establishing lasting cultural archetypes of the noble horse companion. In advertising and branding, horses became powerful symbols of desirable qualities – from the Marlboro Man’s rugged independence to Ferrari’s prancing horse emblem suggesting speed and power. Greeting cards, posters, and mass-produced decorative art featuring romanticized horse imagery became common in middle-class homes, keeping equine symbolism present in everyday life even as actual horses disappeared from urban environments. These commercial adaptations of horse imagery both reinforced traditional symbolic associations and created new meanings suited to consumer culture.

Digital Age Transformations: Virtual Horses and New Media

The digital revolution has created entirely new contexts for equine representation, from sophisticated 3D animations in film to virtual horses in gaming environments. Movies like “War Horse” and “Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron” use cutting-edge technology to create emotionally resonant equine characters that would have been impossible to realize with live animals. The booming industry of equine-themed video games, from racing simulations to horse-care games aimed at young girls, creates interactive relationships with virtual horses that reflect changing human-animal relationships in the digital age. Social media platforms have become showcases for both traditional and digital equine art, with specialized communities sharing millions of horse images daily across platforms like Instagram and Pinterest. Digital manipulation techniques also allow contemporary artists to create surreal and fantastical horse imagery that explores new symbolic territory while referencing historical traditions, demonstrating how this ancient subject continues to evolve with new technological possibilities.

Contemporary Fine Art: Reinterpreting Equine Symbolism

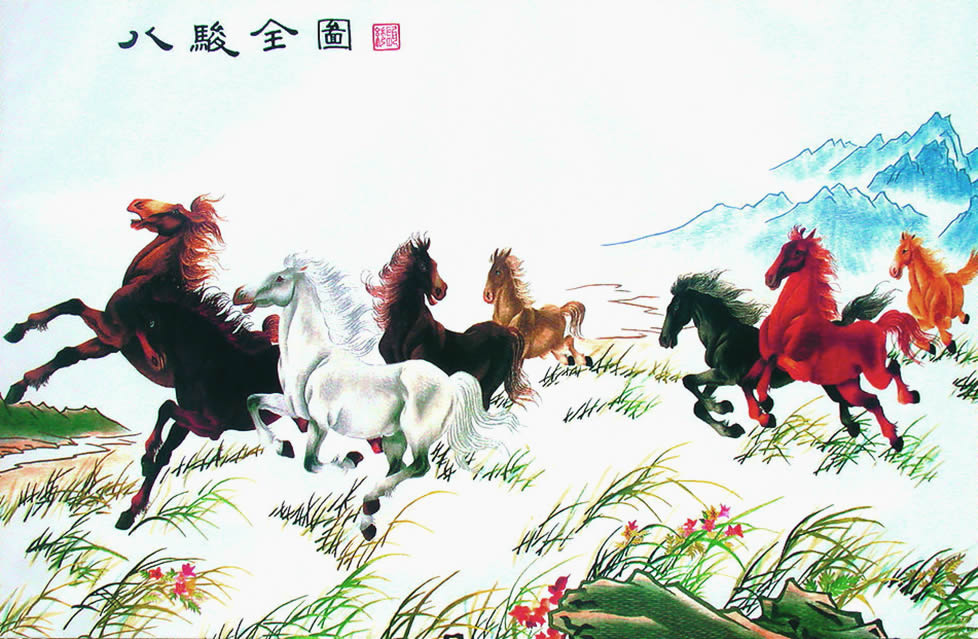

In contemporary fine art, horses continue to inspire significant works that reexamine and reimagine traditional equine symbolism through modern perspectives. Artists like Deborah Butterfield create sculptural horses from found materials like driftwood and scrap metal, commenting on environmental concerns while celebrating equine form. Painters such as Susan Rothenberg gained recognition for neo-expressionist horse imagery that explores psychological and feminist themes, deliberately rejecting the male-dominated traditions of equestrian art. In China, Xu Beihong’s ink-painted horses became symbols of national strength during political upheaval, while contemporary Chinese artists continue this tradition with new interpretations reflecting rapid social change. Native American artists like James Lavadour incorporate horse imagery that reclaims indigenous perspectives on these animals that transformed their cultures. These diverse approaches demonstrate how horses remain potent symbols capable of expressing complex contemporary issues from environmental concerns to cultural identity, proving the remarkable adaptability and enduring power of equine imagery across cultural boundaries and historical periods.

Cultural Preservation: Documenting Traditional Horse Cultures

As traditional horse cultures face pressures from globalization and modernization, documentarians and artists play crucial roles in preserving these vanishing ways of life through visual media. Photographers like Hamid Sardar-Afkhami capture nomadic horse peoples of Mongolia in striking images that record traditional practices dating back to Genghis Khan. Artists from gaucho communities in South America create works celebrating their distinctive horse culture and craftsmanship, from silver-adorned tack to narrative paintings of traditional cattle work. In Central Asia, efforts to document and preserve the ancient sport of buzkashi through film and photography help maintain cultural heritage even as lifestyles change dramatically. European artists document traditional horse fairs and festivals from Appleby to Seville, creating records of customs that connect contemporary communities to centuries-old traditions. These preservation efforts recognize that equine imagery carries not just aesthetic value but serves as an essential repository of cultural memory and identity for communities worldwide whose history has been intertwined with horses for countless generations.

The journey of horses through human art and symbolism reveals much more than changing artistic styles—it tells the story of our evolving relationship with these remarkable animals and with the natural world itself. From sacred beings in prehistoric caves to digital avatars in virtual worlds, horses have adapted to our changing needs for symbols, companions, and inspirations. This remarkable continuity across thousands of years and countless cultures speaks to something fundamental in the human experience—our enduring fascination with these creatures that have walked beside us throughout history. As we continue to reimagine and reinterpret equine imagery in contemporary contexts, we participate in one of humanity’s oldest ongoing artistic conversations, adding new chapters to a visual relationship that has helped define what it means to be human in relation to the natural world and the animals with whom we share it.