Throughout history, horses have transcended their role as mere animals to become powerful symbols in various cultures. Nowhere is this transformation more evident than in the artistic traditions of Persian and Arab civilizations, where horses represent not just transportation or warfare capabilities, but embody deeper cultural values, spiritual beliefs, and societal ideals. The elegant curves of Arabian stallions and the majestic presence of Persian steeds have inspired artists for millennia, creating a rich visual language that connects pre-Islamic traditions with Islamic artistic developments. This symbolic relationship between horses and these cultures reveals fascinating insights into how societies express their deepest values through animal representation in art.

The Historical Significance of Horses in Persian and Arab Societies

Horses revolutionized Middle Eastern and Persian societies, transforming warfare, transportation, commerce, and social hierarchies in ways that would permanently shape cultural development. Archaeological evidence suggests that horse domestication in these regions dates back to approximately 4,000-3,000 BCE, gradually establishing these animals as indispensable companions to human civilization. For nomadic Arab tribes navigating vast desert expanses, horses became essential partners that enabled not only survival but prosperity through trade networks and military advantages. In Persian society, particularly during the Achaemenid and Sassanian empires, horses were so integrally connected to power that royal iconography almost invariably featured equestrian imagery, symbolizing the divine right to rule and martial prowess of kings.

Pre-Islamic Horse Imagery and Zoroastrian Influences

Before Islam’s emergence, horse symbolism in Persian art was deeply intertwined with Zoroastrian religious concepts, where horses often represented divine forces of light and good. Sassanian silver plates frequently depicted royal hunts with intricately detailed horses carrying kings in pursuit of symbolic prey, showcasing both artistic mastery and religious significance. In Zoroastrian cosmology, the sun god Mithra was associated with a chariot pulled by white horses, symbolizing the daily journey of light across the heavens. Archaeological discoveries at sites like Persepolis reveal horse imagery that transcended mere decoration, instead functioning as powerful statements about cosmic order and royal authority in the pre-Islamic Persian worldview. These early symbolic associations would later influence how horses were represented in Islamic-era Persian and Arab art, creating a complex visual tradition that merged ancient symbolism with new religious sensibilities.

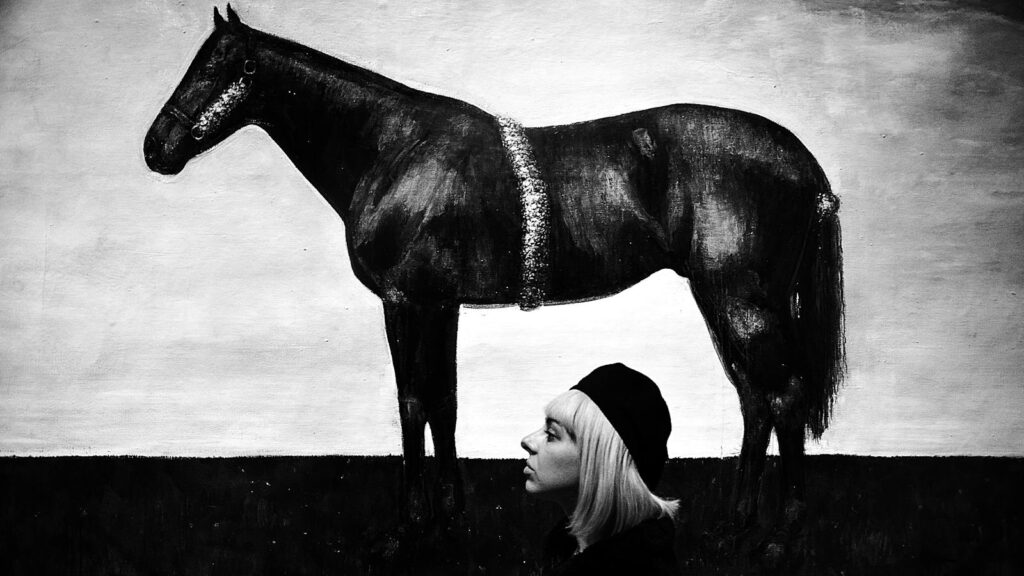

The Arabian Horse in Bedouin Tradition and Poetry

The Arabian horse held an unparalleled position in Bedouin culture, where the relationship between rider and mount often transcended practical considerations to become something akin to familial bonds. Bedouin oral poetry, later collected in works like the Mu’allaqat, frequently elevated horses to legendary status, describing their speed as comparable to natural forces and their loyalty as superior to human companions. The pre-Islamic poetic tradition of the qasida commonly opened with the nasib (elegiac prelude) that might reference a poet’s horse as witness to both conquests and heartbreaks, establishing the animal as memory-keeper of the tribe’s experiences. This poetic representation of horses established visual and symbolic language that would later influence how artists depicted these animals, creating a rich interplay between verbal and visual arts that continues to this day in contemporary Arab artistic expressions.

Horses in Islamic Calligraphy and Decorative Arts

With Islam’s emergence and subsequent prohibitions against figurative representation (varying by region and era), artists developed ingenious ways to incorporate horse symbolism into calligraphic and decorative traditions. Zoomorphic calligraphy evolved as a particularly striking art form, where skilled calligraphers shaped Arabic letters into horse silhouettes, creating dual meanings that satisfied both religious requirements and cultural appreciation for equine symbolism. In textile arts across the Islamic world, stylized horse motifs appeared in carpets, tapestries, and ceremonial fabrics, often with geometric abstraction that maintained the essence of horse symbolism while adhering to religious sensibilities. The horse’s graceful form with its curved neck and flowing tail provided natural inspiration for the curved lines central to Arabic script, creating a visual harmony between written language and equine representation that speaks to the deep cultural significance of both.

Royal Patronage and Equestrian Portraiture

Persian courts, particularly during the Safavid dynasty (1501-1736), commissioned extensive equestrian portraiture that elevated both ruler and mount to mythic proportions, creating visual propaganda that established divine right to rule. These royal equestrian portraits followed specific compositional formulas where the horse’s proportions, posture, and decorative trappings communicated clear messages about the rider’s status, military prowess, and spiritual authority. Court painters like Kamal al-Din Bihzad developed sophisticated techniques for rendering horses with anatomical precision while simultaneously imbuing them with symbolic qualities that reflected royal virtues. In these portraits, the relationship between ruler and horse became a metaphor for the ideal relationship between the sovereign and his kingdom—the perfect horse, responsive to the slightest command, represented a realm in harmony with its divinely appointed leader.

The Horse in Persian Miniature Painting

Persian miniature painting reached extraordinary heights in depicting horses, developing conventions that balanced naturalistic observation with symbolic meaning in manuscriptss like the Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Artists working in this tradition mastered the representation of horses in motion, capturing the dynamism of battle scenes, hunts, and polo matches with remarkable precision despite the small scale of their medium. The horse’s body in Persian miniatures often served as a canvas within a canvas, with decorative saddles, jeweled bridles, and ornate caparisons showcasing the painter’s ability to render intricate patterns while simultaneously conveying the animal’s physical power. Color symbolism played a crucial role in these depictions, with white horses often representing purity or divine connection, black horses suggesting mystery or power, and chestnut or bay horses implying royal authority or earthly vigor.

Buraq: The Celestial Horse in Islamic Mystical Art

The Buraq, the miraculous steed that carried Prophet Muhammad during the Night Journey (Isra and Mi’raj), represents one of the most distinctive equine symbols in Islamic art, blending horse imagery with mystical and angelic qualities. Artists typically depicted this celestial mount with a human face (usually female), wings, and a horse’s body, creating a composite creature that embodied spiritual transcendence and the bridge between earthly and divine realms. In Persian and Mughal miniature traditions, scenes of the Prophet’s Night Journey (usually showing the Prophet veiled or symbolically represented) feature elaborately decorated Buraq figures that communicate the miraculous nature of this spiritual journey. The Buraq image became particularly important in Shi’a visual culture, where it appeared not only in illustrated manuscripts but also on talismans, architectural elements, and ceremonial objects as a protective symbol connecting believers to prophetic blessings.

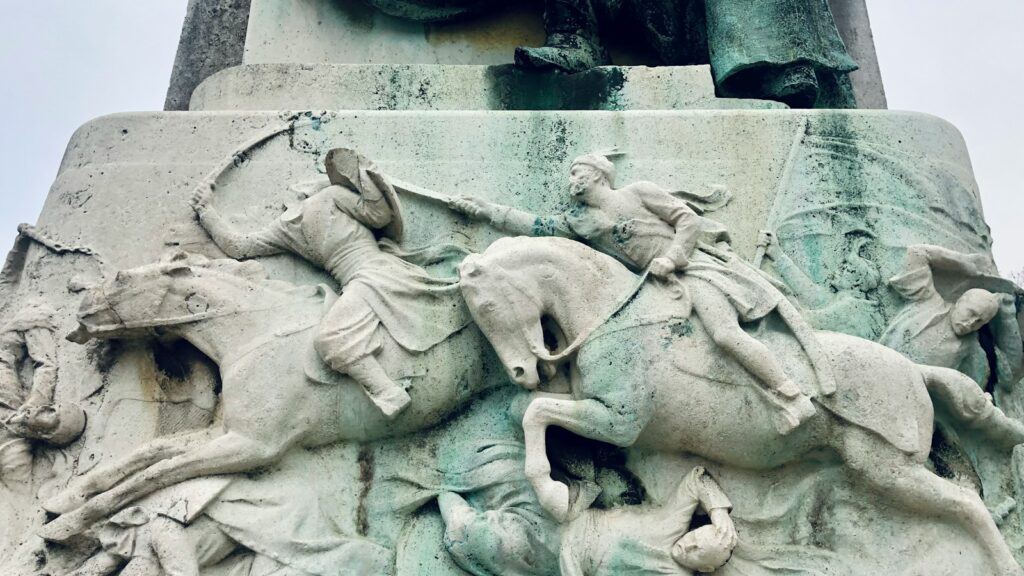

Horses in Battle Scenes and Epic Narratives

Battle scenes in Persian and Arab art elevated horses beyond mere transportation to become active participants in heroic narratives, with distinct personalities and emotional states that mirrored their riders’ experiences. The Shahnameh (Book of Kings), Persia’s national epic, contains numerous illustrated scenes where horses share in the glory and suffering of legendary heroes like Rostam, often depicted with exaggerated features that communicate their supernatural abilities. Artists developed sophisticated visual language to show horses in various battle conditions—rearing in victory, collapsing in defeat, or standing steadfast amid chaos—creating emotional resonance that enhanced the narrative impact. In these battle depictions, the bond between warrior and horse frequently represented ideal loyalty, with famous horse-rider pairs like Rostam and his stallion Rakhsh achieving iconic status comparable to the human heroes of these epics.

The Horse in Arab Scientific and Veterinary Texts

Arab scientific traditions produced remarkably detailed equine anatomical studies and veterinary texts that combined practical knowledge with artistic renderings of extraordinary precision. The 9th-century “Book of Horses” by Al-Jahiz and similar works contained anatomical illustrations that balanced scientific accuracy with aesthetic sensibilities, creating a unique genre that valued horses simultaneously as biological specimens and cultural treasures. These scientific manuscripts often included carefully observed illustrations of horse conformations, gaits, and markings that helped establish standardized terminology still used in evaluating Arabian horses today. The attention to detail in these works reveals the profound respect accorded to horses in Arab intellectual tradition, where understanding equine biology was considered worthy of the same scholarly rigor applied to mathematics, astronomy, or philosophy.

Horses in Religious and Mystical Symbolism

In Sufi mystical traditions, the horse frequently appears as a symbol of the spiritual journey, with different horses representing various stages of the soul’s progression toward divine understanding. Manuscript illustrations of mystical texts like Attar’s “Conference of the Birds” or Rumi’s “Masnavi” sometimes included horse imagery as metaphors for spiritual qualities like patience, endurance, or the controlled power needed to navigate the challenging path to enlightenment. The image of a bridled horse often represented the properly disciplined soul, with the reins symbolizing the restraint of base desires that allows spiritual elevation. In some mystical interpretations, the relationship between rider and horse paralleled the relationship between the rational mind and the physical body, with mastery of horsemanship serving as an allegory for mastery of one’s own nature.

Contemporary Interpretations and Artistic Legacy

Modern Arab and Persian artists continue to engage with equine symbolism, reinterpreting traditional motifs through contemporary artistic languages that speak to both cultural heritage and present-day concerns. Painters like Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli incorporate stylized horse forms into modernist compositions that reference ancient Sassanian imagery while exploring contemporary themes of national identity and cultural continuity. In the Arabian Peninsula, horse sculpture has experienced a renaissance with monumental public works that celebrate the Arabian horse as a symbol of cultural pride and historical connection. Digital artists across the Persian and Arab world now create works that blend traditional equine symbolism with new media, reaching global audiences while maintaining connections to artistic traditions thousands of years old.

Regional Variations in Equine Representation

Distinct regional styles developed across the Persian and Arab worlds, with Ottoman, Mughal, North African, and various Persian schools each developing characteristic approaches to equine representation. Ottoman art typically featured more robust, powerfully built horses that emphasized military might, while Persian Safavid paintings often showed more elegant, elongated proportions that highlighted grace and refinement. Mughal artists in India, influenced by both Persian traditions and local aesthetic sensibilities, created horse imagery that balanced naturalistic observation with symbolic decoration, often incorporating incredibly detailed floral patterns into horse trappings. These regional variations reveal how horse symbolism, while sharing common cultural roots, adapted to express specific local values, historical experiences, and aesthetic preferences throughout the vast geographic expanse of Persian and Arab cultural influence.

Conclusion

The horse in Persian and Arab art represents far more than an animal—it embodies cultural values, spiritual beliefs, and historical identities that continue to resonate in contemporary artistic expressions. From pre-Islamic religious symbolism to Islamic calligraphic innovations, from scientific illustration to mystical representation, horses have galloped through the artistic imagination of these cultures for millennia. This enduring relationship between artists and equine subjects reveals how deeply intertwined horses became with human expression, serving as vehicles not just for physical transportation but for communicating complex ideas about power, beauty, spirituality, and cultural identity. As modern artists continue to reference and reinvent this rich symbolic tradition, the horse remains a powerful emblem connecting contemporary creativity with ancient artistic wisdom.