The vast grasslands of Central Asia have witnessed one of humanity’s most profound partnerships—the relationship between nomadic peoples and their horses. This bond transcended mere utility, becoming the cornerstone of civilizations that stretched from the Caspian Sea to Mongolia’s eastern steppes. For thousands of years, horses enabled these mobile societies to thrive in harsh environments where settled agriculture proved challenging. The horse transformed every aspect of nomadic existence—from warfare and transportation to social structures and spiritual beliefs. This symbiotic relationship created distinct cultural identities that would ultimately shape world history through migrations, conquests, and trade. The story of Central Asian nomads and their equine companions represents one of humanity’s most successful adaptive strategies, allowing relatively small populations to project influence across continents and establish empires of unprecedented size.

The Origins of Horse Domestication in Central Asia

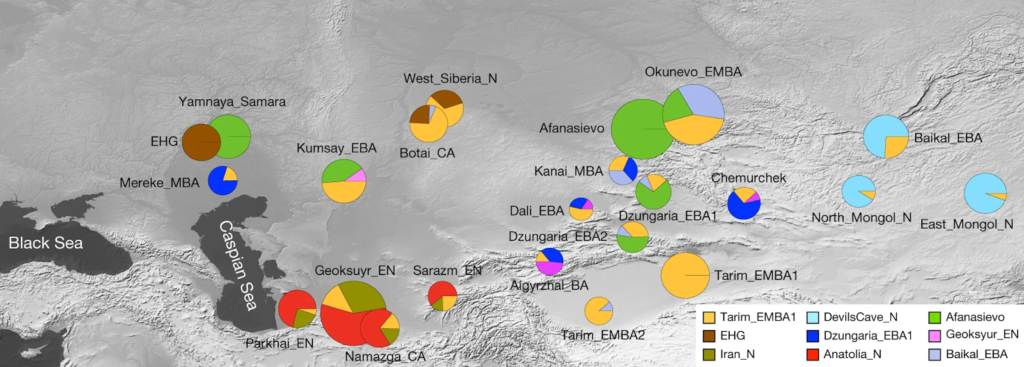

Archaeological evidence suggests that horse domestication first occurred in the Central Asian steppes around 3500-3000 BCE, with the earliest confirmed evidence coming from Kazakhstan’s Botai culture. Unlike other domesticated animals, horses weren’t initially valued primarily for meat or milk, but for their unprecedented mobility advantages. The Botai people left behind bits, bridles, and pottery with traces of mare’s milk, providing tangible evidence of this pivotal relationship forming. The domestication process likely began with horses being hunted for food, then managed in loose herds, and finally becoming fully integrated partners in human society. This transition fundamentally altered human capabilities in the region, enabling populations to cover vast territories and manage larger herds of other livestock than previously possible.

Mobility Revolution: How Horses Transformed Nomadic Life

Before horse domestication, human communities in Central Asia were relatively sedentary despite practicing animal husbandry with sheep, goats, and cattle. The introduction of riding horses dramatically expanded the territory a single group could effectively utilize, increasing their resource base exponentially. A mounted herder could cover five times the distance of someone on foot, monitor animals across widely dispersed pastures, and rapidly respond to threats or changing conditions. This mobility revolution enabled true nomadism to emerge as a viable and highly adaptive lifestyle specifically suited to the region’s vast steppes with their seasonal rainfall patterns. Perhaps most significantly, horses allowed nomadic groups to maintain cultural cohesion despite being spread across enormous territories, as riders could travel between distant camps in days rather than weeks, maintaining communication networks crucial for social and political organization.

Warfare and Empire Building: The Horse as Military Technology

The mounted warrior represented one of history’s most significant military innovations, completely reshaping power dynamics across Eurasia. Central Asian horsemen developed composite bows that could be effectively used from horseback, creating the world’s first mobile artillery platform capable of rapid strikes and equally rapid retreats. The Scythians, Xiongnu, Huns, Turks, and Mongols all leveraged this military advantage to establish vast empires despite their relatively small populations compared to the agricultural societies they conquered. Genghis Khan’s campaigns represent the pinnacle of this horse-based military tradition, with Mongol cavalry units capable of covering 100 miles in a single day during critical campaigns. These mounted forces couldn’t have existed without specialized breeding programs that developed horses with the endurance, temperament, and physical capabilities required for warfare, with each warrior typically maintaining a string of multiple mounts to maintain mobility during campaigns.

The Specialized Breeds of Central Asia

Central Asian nomads developed distinct horse breeds specifically adapted to their harsh environment and varied needs, creating bloodlines prized for different qualities. The Akhal-Teke, one of the world’s oldest surviving horse breeds originating in modern Turkmenistan, was renowned for its speed, endurance, and distinctive metallic coat sheen, making it both practically valuable and symbolically important. The Mongolian horse, smaller but incredibly hardy, could survive temperatures ranging from -40°F to 86°F while requiring minimal care, foraging beneath snow in winter without supplemental feeding. The Kazakh horse developed exceptional cold tolerance and the ability to maintain condition on sparse vegetation, while the Ferghana horse (the “heavenly horse” sought by Chinese emperors) combined beauty with performance. These specialized breeds represented thousands of years of selective breeding, each adapted to specific ecological niches within the broader steppe environment.

The Horse in Nomadic Material Culture

The central importance of horses in nomadic life is abundantly reflected in the material culture excavated from archaeological sites across Central Asia. Elaborate horse gear—including ornate bridles, saddles, and decorative trappings crafted from leather, felt, wood, and precious metals—demonstrates both the practical importance and symbolic significance of equine companions. The Pazyryk frozen tombs in the Altai Mountains preserved extraordinary examples of horse equipment, including a remarkable felt saddle cover with intricate appliqué designs dating to the 4th-3rd centuries BCE. The importance of horses is further reflected in portable art depicting equine themes, ranging from small gold plaques to elaborate tattoos preserved on frozen bodies, showing horses in various contexts from hunting scenes to mythological narratives. Archaeological evidence also reveals specialized tools for horse care, horse-related structures at campsites, and ritualized horse burials accompanying elite human interments, all testifying to the animal’s central position in daily life.

Horses and Nomadic Economic Systems

Horses functioned as the engine of nomadic economic systems, enabling a pastoral lifestyle that would have been impossible without equine mobility. Beyond their transportation value, horses represented significant wealth in themselves, with herd sizes directly correlating to a family’s prosperity and social standing. A sophisticated understanding of horse breeding created economic specialization, with some groups becoming renowned for producing superior animals that commanded premium prices in trade networks. The ability to rapidly move camps allowed nomads to efficiently follow seasonal pasture cycles, maximizing productivity from lands that couldn’t support fixed agriculture. Notably, horses also facilitated long-distance trade, with nomadic groups controlling vital segments of the Silk Road and other trade networks, collecting tolls, providing protection, and offering remount services to caravans traversing their territories—creating wealth without needing to engage directly in agricultural production.

Spiritual Significance and Horse Sacrifice

Horses occupied a unique position in the spiritual worldview of Central Asian nomads, often serving as intermediaries between human and divine realms. Many origin myths featured horses prominently, and celestial horses were believed to carry shamans between worlds during spiritual journeys. The ritual sacrifice of horses at important ceremonies and burials was widespread across different nomadic cultures, reflecting the animal’s immense value and perceived spiritual power. The Altai burial mounds contained elaborately prepared horses with facial masks, decorative antlers, and intricate trappings—preparations for their continued service in the afterlife. Even after the adoption of world religions like Buddhism and Islam, horse symbolism remained deeply embedded in folk practices and cultural expressions. Horse milk (kumis) held ritual significance beyond its nutritional value, featuring prominently in ceremonies where it was offered to spirits and shared among community members to reinforce social bonds.

Social Structures and Horse Ownership

Horse ownership patterns fundamentally shaped social hierarchies within nomadic societies, with leadership positions typically held by those who possessed the largest or finest herds. The distribution of horses within clans reflected and reinforced existing power structures, with elite warriors maintaining strings of specialized mounts while ordinary herders might have access to fewer or less prestigious animals. Children began riding at extraordinarily young ages—often by age three—with riding skill development being a central aspect of education and social integration. Horses also featured prominently in marriage negotiations, frequently constituting a significant portion of bride prices and determining a family’s ability to form advantageous alliances. The collaborative nature of horse herding necessitated cooperative social structures extending beyond immediate family units, creating complex networks of obligation and reciprocity that defined nomadic social organization and leadership patterns.

Horse Milk and Meat in Nomadic Diet

Horse products formed a crucial component of the nomadic diet, providing essential nutrition in environments where agricultural options were limited. Mare’s milk, fermented into mildly alcoholic kumis (also called airag), offered a portable, storable source of vitamins and calories that could sustain communities through harsh winters. This nutritional strategy represented an ingenious adaptation, as horses could efficiently convert steppe grasses inedible to humans into highly nutritious milk and meat that sustained their human partners. Horse meat, preserved through traditional methods of drying and smoking, provided high-protein reserves for winter months when other food sources were scarce. The importance of these horse-derived foods extended beyond mere sustenance, as the shared consumption of kumis and horsemeat at gatherings reinforced social bonds and cultural identity, with specific distribution patterns reflecting social hierarchies within the group.

Differences in Horse Usage Across Steppe Cultures

While horses were universally important across Central Asian nomadic societies, distinctive regional variations emerged in how different groups incorporated equines into their cultural practices. The Scythians of the western steppes developed elaborate horse burials with chariots and teams of sacrificed horses, reflecting their particular cosmological beliefs and social structures. Mongol horsemen perfected a distinctive riding style featuring short stirrups and specific bow designs optimized for mounted archery, contrasting with the longer stirrups seen in more westerly Turkic groups. Cultural differences also appeared in training methods, with some groups like the Kyrgyz valuing games that showcased mounted combat skills, while others emphasized endurance or speed qualities. Variations in horse equipment, decoration styles, and preferred coat colors all helped define cultural identities among groups that might otherwise share many practices, creating visual markers that signaled affiliation visible across vast distances.

Cultural Exchange and Horse Diplomacy

Prized Central Asian horses became important diplomatic currency, exchanged as prestigious gifts that cemented alliances and signaled respect between political entities. The famous “blood-sweating” Ferghana horses were so coveted by Han Dynasty China that Emperor Wu launched military campaigns specifically to acquire them, demonstrating their extraordinary value as diplomatic assets. Horse-trading networks facilitated cultural exchange across vast distances, introducing new technologies, artistic motifs, and religious ideas alongside the animals themselves. Specialized knowledge about horse breeding, training, and care traveled with the animals, creating lasting cultural impacts in recipient regions where these practices were adapted to local conditions. The horse’s capacity to rapidly transport people made it the primary vehicle for diplomatic missions between distant powers, facilitating negotiation and information exchange that would have been impossible in the pre-horse era.

Modern Legacy of the Horse-Nomad Relationship

The ancient relationship between Central Asian peoples and their horses continues to shape cultural identities and practices in the region today, despite significant modernization. Traditional horse games remain important cultural touchstones, with events like kokpar (a mounted tug-of-war using a goat carcass) and kyz kuu (a horseback “chase the girl” race) attracting participants and spectators who connect to their nomadic heritage through these demonstrations of riding skill. Contemporary breeding programs work to preserve indigenous horse types that face dilution from crossbreeding with imported breeds, recognizing these animals as living cultural heritage. The symbolic importance of horses persists in national identities across Central Asia, appearing prominently in state emblems, currency, and public monuments from Kazakhstan to Kyrgyzstan. Even as motorized transportation has replaced horses for many practical purposes, ceremonial and recreational riding traditions maintain cultural knowledge that stretches back millennia, preserving the essence of this profound human-animal partnership for future generations.

The relationship between Central Asian nomads and their horses represents one of history’s most successful adaptive strategies—a partnership that transformed vast, challenging landscapes into the foundation for distinctive civilizations with global impact. This equine revolution enabled relatively small populations to establish empires that connected East and West, facilitating unprecedented cultural and technological exchange across continents. The material culture, social structures, warfare techniques, and spiritual traditions that developed from this relationship continue to influence modern Central Asian identities long after the practical necessity of horse nomadism has faded. As contemporary nations in the region navigate their place in the global community, the horse remains a powerful symbol connecting present to past, urban to rural, and innovation to tradition—a living legacy of one of humanity’s most transformative interspecies relationships.