The relationship between humans and horses spans thousands of years, evolving from one of predator and prey into a partnership that would shape the course of human civilization. Long before horses pulled plows or carried knights into battle, they transformed how early societies functioned, communicated, and expanded. The domestication of horses around 3500 BCE in the Eurasian steppes set in motion a cascade of developments that enabled the rise of the world’s first sprawling empires. These majestic animals became more than mere beasts of burden—they served as catalysts for technological innovation, military dominance, trade expansion, and cultural exchange. The story of early empire-building is, in many ways, inseparable from the story of how humans harnessed the power, speed, and endurance of the horse.

The Domestication Revolution

Archaeological evidence suggests that horses were first domesticated by the Botai culture in northern Kazakhstan around 3500 BCE, though some evidence points to even earlier domestication by other steppe peoples. This momentous achievement did not happen overnight but was the culmination of generations of interaction between humans and wild equines. Initially, horses were likely domesticated for their meat and milk, providing a reliable protein source for nomadic populations. Evidence of bit wear on teeth and the presence of horse milk residue in ancient pottery confirms this early relationship. The transition from using horses as food to utilizing them for transportation represented one of humanity’s most significant technological leaps, comparable in importance to the harnessing of fire or the invention of agriculture.

Mobility and the Expansion of Territory

The horse dramatically transformed human mobility, enabling people to travel distances that were previously unimaginable. While humans can typically walk about 20 miles per day, a horse and rider could cover 40 to 60 miles, effectively tripling the area that could be governed by a single political entity. This expanded range allowed early rulers to control larger territories, communicate more efficiently with distant regions, and respond more swiftly to border threats or internal rebellions. The Achaemenid Empire, for example, established a sophisticated relay system known as the Royal Road, where fresh horses and riders could carry messages across the 1,600-mile empire in just seven days—a journey that would have taken months on foot. This newfound mobility fundamentally changed the scale at which human societies could function, laying the foundation for imperial expansion.

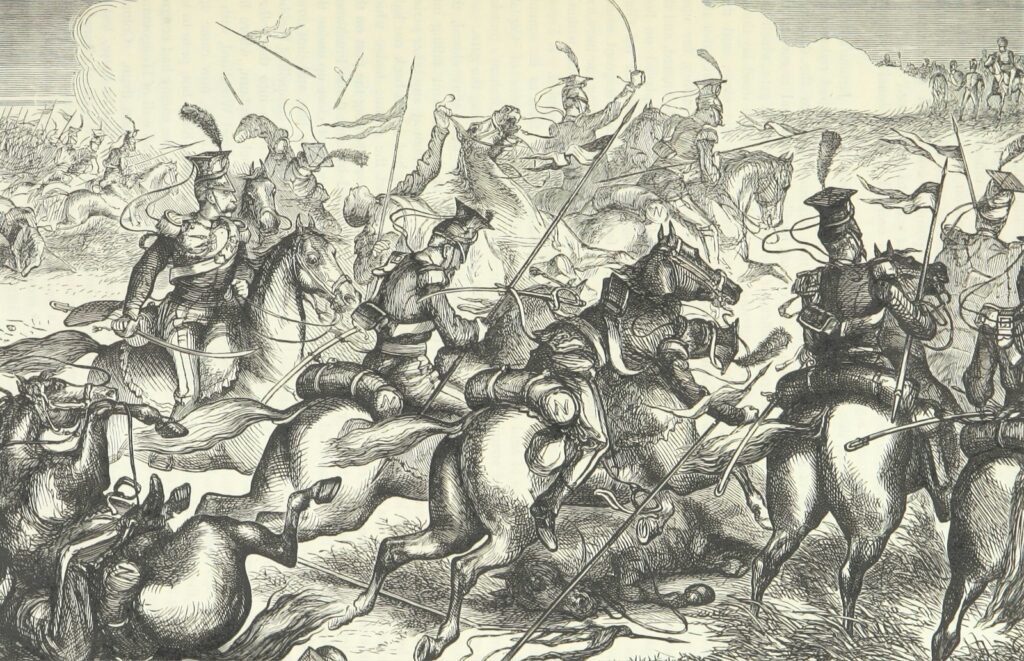

The Military Advantage of Mounted Warriors

Perhaps no aspect of horse domestication was more revolutionary for empire-building than the military advantage conferred by mounted warriors. Cavalry forces could move swiftly across diverse terrain, launch surprise attacks, and retreat quickly when necessary. The Scythians, nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppe, developed mounted archery to devastating effect, allowing them to release arrows while riding at full gallop. This combination of mobility and firepower made them formidable opponents and enabled them to dominate vast territories. Later, the Assyrians, Persians, and Macedonians incorporated cavalry as essential components of their military strategies, using mounted units to outflank infantry, pursue retreating enemies, and secure rapid victories. Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Persian Empire might not have been possible without his skilled cavalry, which often turned the tide in crucial battles like Gaugamela

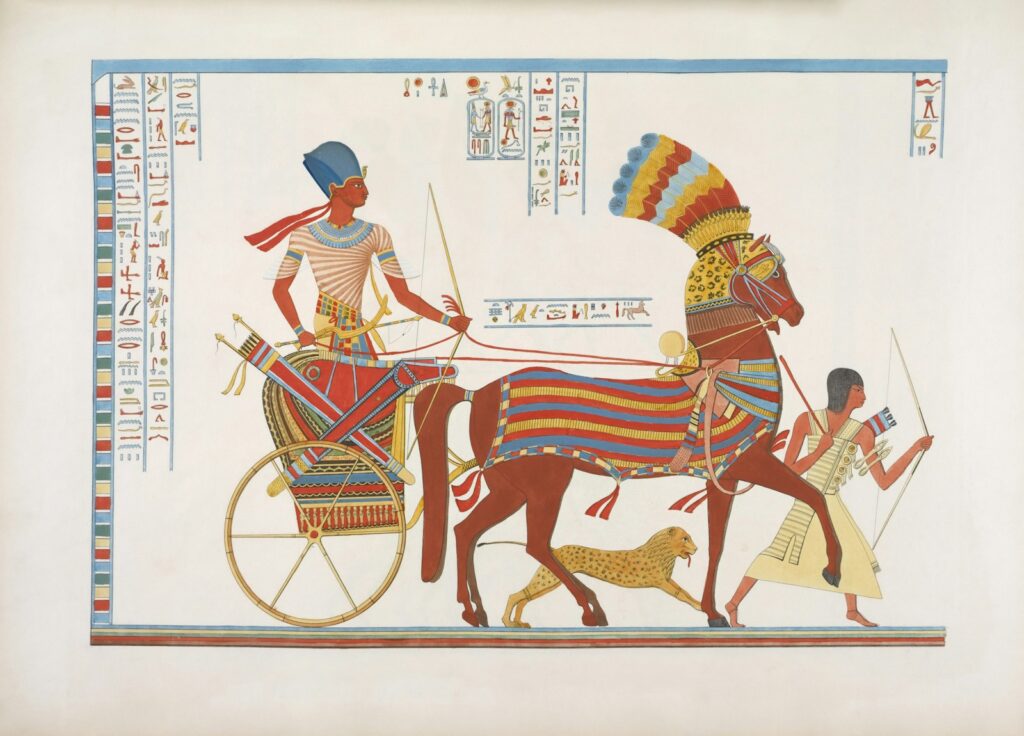

The Chariot Revolution

Before mounted cavalry became widespread, the invention of the horse-drawn chariot around 2000 BCE revolutionized warfare and helped lay the foundation for some of the earliest empires. The chariot combined the speed of horses with a stable platform from which archers could shoot creating a powerful mobile weapons system. The Hittite Empire in Anatolia mastered chariot warfare and used this technology to dominate much of the Near East during the Late Bronze Age. Similarly, the Egyptian New Kingdom expanded its borders significantly after adopting and refining chariot technology. In China, the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) employed chariots as symbols of royal power and military strength, with archaeological evidence revealing elaborate burial practices where chariots accompanied elite warriors into the afterlife. The specialized training, upkeep, and resources required for chariot forces also deepened social divisions, reinforcing the hierarchical structures that supported early imperial rule.

Transportation of Goods and Imperial Trade Networks

Horses dramatically expanded the trade capabilities of ancient civilizations, enabling the transport of goods across vast distances. Pack horses could carry up to 200 pounds of merchandise over rugged terrain where wheeled vehicles couldn’t travel, opening new trade routes that connected distant regions. The network of paths that would eventually become the Silk Road began with horse caravans linking China to the Mediterranean world. This growing trade generated wealth that could be taxed, fueling imperial treasuries and supporting further expansion. The Han Dynasty in China invested heavily in horse breeding and trade to acquire superior horses from Central Asia, recognizing their value for both military and commercial purposes. Imperial control over horse-driven trade routes became a major source of power, with empires establishing outposts, caravanserais, and garrison towns to protect these vital economic lifelines.

Horses and Communication Networks

The ability to rapidly transmit information across vast distances was crucial for maintaining imperial control—and horses made this possible. The Persian Empire under Darius I established the world’s first sophisticated postal system, with horseback couriers carrying messages along carefully maintained royal roads. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, these messengers followed the principle that “neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor darkness of night” would prevent them from completing their appointed rounds—a motto later adopted by the United States Postal Service. The Roman cursus publicus (imperial post) further refined this system, with way stations placed roughly 25 miles apart—the distance a horse could travel before needing rest. These communication networks allowed imperial decrees to be delivered quickly, intelligence to be reported promptly, and administrative control to be maintained over distant provinces.

The Steppe Connection: Nomadic Horsemen and Empire Building

The greatest horsemasters of the ancient world were the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppe, who lived in close symbiosis with their mounts. These groups—including the Scythians, Sarmatians, Xiongnu, and later the Huns and Mongols—developed riding techniques and technologies that made them nearly unbeatable in their environment. Many established empires were forced to devote enormous resources to defending against these mounted nomads, with China constructing the Great Wall in part as a response to the threat they posed. Paradoxically, these same nomadic horse cultures also contributed to empire-building, as settled states adopted their cavalry tactics or employed them as mercenaries. The relationship between steppe nomads and agricultural empires was complex, shaped by trade, warfare, cultural exchange, and occasional conquest—as when the nomadic Yuezhi were displaced by the Xiongnu, triggering a chain reaction that contributed to the fall of Greco-Bactria and the rise of the Kushan Empire in northern India.

Horse Breeding and Imperial Resources

As horses became central to imperial power, managing their breeding and supply grew into a matter of state importance. The Hittites produced one of the earliest known texts on horse training, offering detailed instructions for the care of chariot horses. Neo-Assyrian kings established royal studs to ensure a steady supply of quality mounts for their military campaigns. In China, during the Zhou Dynasty, the office of the Master of Horses became one of the highest-ranking positions in the imperial administration, overseeing breeding programs and maintaining cavalry readiness. The resource demands of sustaining large horse populations—including extensive grazing lands, skilled personnel, and storage for fodder—shaped imperial policies on land use and agriculture. Though the infrastructure for horse breeding required significant investment, it paid dividends in military strength and administrative control.

Horses and Social Stratification in Empires

The possession of horses contributed significantly to social stratification within early empires, both creating and reinforcing elite status. The cost of acquiring and maintaining horses meant that mounted warriors typically came from wealthy backgrounds, forming a military aristocracy in many societies. In the Roman Empire, the equestrian order (ordo equester) became a formal social class—ranked below senators but above common citizens—with property requirements tied to the ability to support a horse. In China, horse ownership was restricted by law at various times, with penalties for commoners who rode without authorization. In Persia, nobility was partly defined by horsemanship, with young aristocrats taught to “ride, draw the bow, and speak the truth,” as noted by Herodotus. This horse-based social structure gave early empires a ready-made officer class for their armies and a pool of administrators loyal to the system that elevated their status.

Technological Innovations Driven by Horsemanship

The integration of horses into human societies spurred a wave of technological innovations that supported imperial administration and expansion. The invention of the saddle around 800 BCE improved rider stability and comfort, while the later adoption of stirrups (between 200–400 CE) revolutionized mounted combat by allowing riders to stand in the saddle and deliver more powerful blows. Advances in metallurgy were partly driven by the need for stronger bits, bridles, and horseshoes—techniques that were later applied to other areas. Road systems built to support horse traffic required engineering solutions for drainage, surfacing, and bridge construction, with the Roman road network standing as one of the most remarkable examples. These developments, initially motivated by the needs of mounted forces, left behind infrastructure that facilitated trade, communication, and administrative control—key elements in maintaining imperial power.

Horses in Imperial Iconography and Legitimacy

Horses featured prominently in the symbolism and propaganda of ancient empires, helping to legitimize imperial rule. Persian kings were often depicted as masterful horsemen, with the famous reliefs at Persepolis showing royal horses in elaborate harnesses. Alexander the Great’s beloved horse, Bucephalus, became almost as legendary as the conqueror himself, appearing in numerous artistic depictions. In China, imperial tombs included terracotta horses alongside warrior figures, most famously in the mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huang. The Roman equestrian statue—depicting the emperor on horseback—emerged as a powerful symbol of leadership, with the bronze statue of Marcus Aurelius standing as one of the few to survive from antiquity. These visual representations linked imperial authority with mastery over the powerful and prestigious horse, implying that those who could command such animals were naturally fit to govern people as well.

Cultural Exchange Via Horseback

Horses facilitated unprecedented cultural exchange between distant regions, contributing to the cosmopolitan nature of many ancient empires. Mounted messengers, traders, and diplomats carried not only material goods but also ideas, technologies, and beliefs across vast distances. The spread of Buddhism from India to Central Asia and eventually to China was aided by horse-riding merchants and missionaries traveling along early Silk Road routes. Persian religious concepts reached the Mediterranean world in part due to the mobility offered by horseback travel. Languages evolved and spread along these horse-enabled trade routes, with loanwords related to horses often passing between cultures—the English word “horse” shares roots with terms found in Celtic, Slavic, and other language families. This cultural cross-pollination enriched imperial societies and introduced new technologies and ideas that could be adapted to strengthen state power.

The Legacy of Horse-Powered Empires

The influence of horses on early empire-building extended far beyond the ancient world, shaping systems of governance, military organization, and transportation networks that endured for millennia. Roman cavalry techniques influenced Byzantine military strategies, which in turn shaped medieval European warfare. The postal systems created by ancient empires evolved into communication networks that later supported colonial expansion. Even with the rise of mechanized transport in the modern era, many military units retained horse cavalry into the 20th century, with the last major cavalry charge occurring during World War II. Today’s road networks often trace ancient routes first established for horse travel, and “horsepower” remains the standard for measuring engine strength—a linguistic echo of how essential these animals once were to human progress. The partnership between horses and empire-building is one of history’s most influential, transforming societies and leaving a lasting imprint on our political, military, and cultural development.

The story of early empires cannot be told without recognizing the transformative role of the horse. From the steppes of Central Asia to the Mediterranean basin, from China to Mesoamerica, horses changed the very calculus of power, distance, and communication. They offered the mobility that enabled rulers to govern vast territories, the military edge that secured conquests, and the transportation systems that kept imperial economies running. The bond between humans and horses laid the foundation for the rise of the world’s first great empires, influencing the course of civilization for thousands of years. While steam, combustion, and electricity eventually replaced horsepower, the patterns forged during that early partnership still shape our world—reminding us that some of humanity’s most profound revolutions were made possible not by invention alone, but by our enduring connection to the animals beside us.