Throughout history, horses have captivated human imagination, leading to the creation of legendary equine figures that transcend reality. From Pegasus to Sleipnir, mythical horses have populated stories across civilizations, embodying supernatural powers and divine connections. The concept of mythical mares—female horses with extraordinary abilities—has particular significance in folklore worldwide. These legendary equines challenge our understanding of what separates historical fact from fantastical fiction, raising the question: what might be the most mythical mare ever conceived in human storytelling? This article explores famous mythical mares across cultures, their significance, and what might earn the title of “most mythical” among these legendary equines.

The Enduring Appeal of Mythical Horses

Humans have shared a profound connection with horses for thousands of years, developing relationships that transcend mere domestication. This special bond has elevated horses to symbolic status in myths and legends worldwide, representing freedom, power, and transcendence. Mythical horses often embody the qualities humans admire most—speed, strength, loyalty, and wisdom—while adding supernatural elements that reflect our desire to transcend ordinary limitations. Unlike other mythological creatures that are completely fabricated, mythical horses often begin with the familiar form of an actual horse before supernatural abilities are added, creating a bridge between the everyday world and the realm of the extraordinary. This familiar-yet-fantastical nature helps explain why horse mythology remains relevant across cultures and throughout time, even in our modern world.

Epona: The Celtic Divine Mare

Among the most revered mythical mares in ancient European tradition stands Epona, the Celtic horse goddess whose worship spread throughout the Roman Empire. As the only Celtic deity officially recognized in Rome, Epona was particularly venerated by cavalry units, reflecting her association with horses, sovereignty, and fertility. Depicted as either riding a mare or as a mare herself, Epona protected horses, their riders, and fostered abundance in agricultural communities. Archaeological evidence shows her cult was especially strong in Gaul (modern France) and parts of Britain, with numerous stone carvings and temples dedicated to her worship. Her association with fertility extended beyond horses to include crop success and human reproduction, making her a multifaceted protective force in ancient Celtic society.

Al-Buraq: The Lightning Mare of Islamic Tradition

In Islamic tradition, Al-Buraq stands as perhaps one of the most extraordinary mythical mares ever described. This magnificent creature, smaller than a mule but larger than a donkey, is typically depicted with a woman’s face, peacock’s tail, and wings. According to Islamic belief, Al-Buraq transported the Prophet Muhammad during the miraculous Night Journey (Isra and Mi’raj) from Mecca to Jerusalem and then through the seven heavens. What makes Al-Buraq particularly remarkable is her speed—her name derives from the Arabic word for lightning, as she could place her hooves at the farthest boundary of her sight with each stride, essentially traveling at the speed of light. This transcendent mare serves as the ultimate example of a mythical horse connecting the earthly and divine realms, making her a strong contender for the most mythical mare in religious traditions.

Macha’s Twins: The Curse of the Ulster Men

In Irish mythology, one of the most poignant tales involves the goddess Macha, who was forced to race against King Conchobar’s horses while heavily pregnant. Despite her condition, Macha—in human form—defeated the king’s finest steeds before collapsing and giving birth to twins. With her dying breath, she cursed the men of Ulster to experience the pains of childbirth in times of greatest peril, a curse that would last for nine generations. Though not mythical horses themselves, Macha’s twin offspring were said to transform into exceptional horses that possessed supernatural speed and endurance inherited from their divine mother. These twins represent the complex relationship between femininity, equine power, and divine punishment in Celtic mythology, demonstrating how mythical horses often serve as vehicles for moral lessons about human hubris and divine justice.

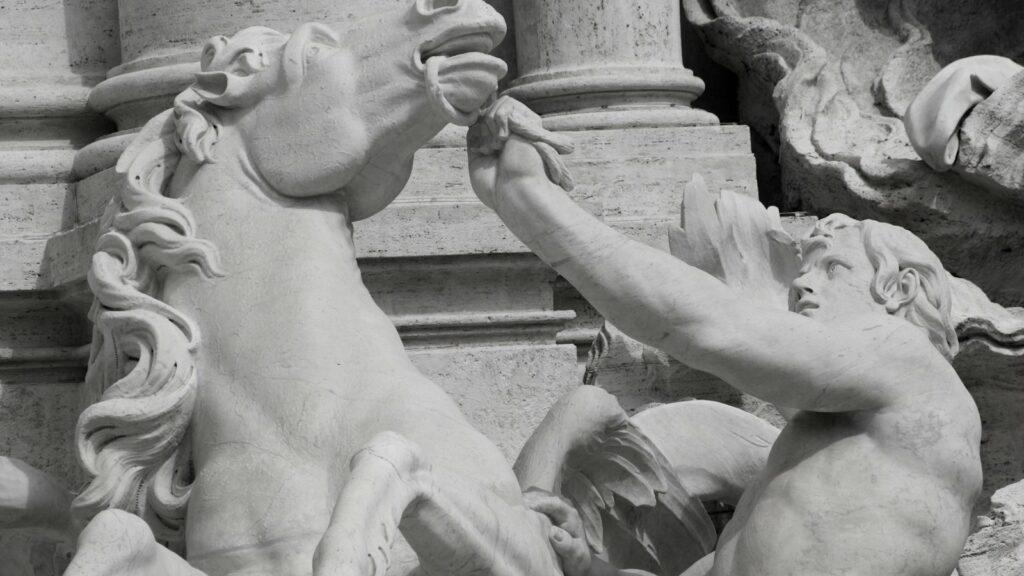

Xanthos and Balios: The Immortal Mares of Achilles

Greek mythology presents us with Xanthos and Balios, immortal mares gifted to Peleus (Achilles’ father) by the gods and later used by Achilles in the Trojan War. These extraordinary mares were the offspring of Zephyrus, the West Wind, and the harpy Podarge, giving them divine parentage and supernatural abilities. Homer’s Iliad describes how these mares could run as swiftly as the wind and even possessed the power of speech, famously prophesying Achilles’ death. Their divine nature is emphasized when they weep at Patroclus’ death, showing emotional depth rarely attributed to animals in ancient literature. As immortal beings with prophetic abilities and divine lineage, these mares represent the Greek concept of horses as liminal creatures—existing between the mortal and divine realms—making them among the most profound mythical mares in classical literature.

Sleipnir’s Mother: Loki as a Mare

One of the most bizarre and fascinating mythical mare stories comes from Norse mythology, where the trickster god Loki transformed himself into a mare to distract the stallion Svaðilfari. This extraordinary situation arose when the gods hired a builder to construct Asgard’s walls, promising the sun, moon, and goddess Freya as payment if completed within an impossible timeframe. When the builder and his powerful stallion Svaðilfari seemed likely to succeed, Loki transformed into a mare in heat to lure the stallion away, preventing the work’s completion. This deception led to Loki—while in mare form—becoming pregnant and later giving birth to Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse that became Odin’s steed. This tale presents perhaps the most unusual mythical mare, as Loki’s temporary transformation resulted in mothering the greatest mythical horse in Norse tradition, creating an unparalleled example of boundary-crossing in mythological narratives.

The Mares of Diomedes: Flesh-Eating Equines

Greek mythology contains some of the most terrifying mythical mares in the form of the man-eating Mares of Diomedes. These four savage horses—Podargos, Lampon, Xanthos, and Deinos—belonged to Diomedes, the king of Thrace, who fed them human flesh to make them wild and untamable. As part of his eighth labor, Heracles was tasked with capturing these murderous mares and bringing them to King Eurystheus. Various versions of the myth describe how Heracles succeeded, either by feeding Diomedes to his own horses to satisfy their hunger or by defeating the Bistones who guarded the mares. These flesh-eating mares represent the dangerous and untamed aspects of horse nature that ancient Greeks feared, standing in stark contrast to the noble, divine horses like those of Apollo or Poseidon. Their man-eating habits and connection to a laborious challenge for a demigod elevate them to particularly mythical status among equine legends.

Kanthaka: Buddha’s Faithful Mare

In Buddhist tradition, Prince Siddhartha Gautama (who would become the Buddha) had a loyal horse named Kanthaka, sometimes described as a mare in certain traditions. When Siddhartha decided to renounce his royal life to seek enlightenment, Kanthaka carried him away from the palace in the middle of the night, with the gods muffling the sound of hoofbeats. According to legend, this remarkable horse understood the significance of the prince’s journey and leaped over the city walls—a distance of immense proportions—to help Siddhartha escape. Upon realizing that her master would continue his spiritual journey on foot, Kanthaka was said to have died of heartbreak, demonstrating profound emotional connection and awareness uncommon in animals. Kanthaka was subsequently reborn in Tāvatiṃsa heaven as a reward for this service to the future Buddha, making this loyal mare a central figure in one of the world’s major religious traditions.

The Kelpie: Scotland’s Shapeshifting Water Mare

Scottish folklore brings us the kelpie, a shapeshifting water spirit that often appears as a beautiful horse near bodies of water, particularly appealing to children. Despite its enchanting appearance, the kelpie harbors sinister intentions—its skin is adhesive, trapping anyone who touches it, whereupon the creature drags its victims underwater to devour them. Female kelpies, or water mares, were said to be particularly dangerous during storms, when they would emerge from lochs to feign distress and lure compassionate humans to their doom. Some legends claim that capturing a kelpie’s bridle gives power over the creature, forcing it to grant wishes or perform labor. The kelpie represents the dangerous allure of unknown waters and the unpredictable nature of horses, combining beauty and terror in a way that exemplifies humanity’s ambivalent relationship with the natural world.

Rhiannon’s White Mare: The False Accusation

Welsh mythology presents Rhiannon, a powerful figure associated with horses who first appears riding a magnificent white mare that no one can catch despite its apparently slow pace. After marrying Pwyll, Rhiannon gives birth to a son who mysteriously disappears, leading her maids to falsely accuse her of killing the child. As punishment, Rhiannon must sit by the castle gate for seven years, telling her story to travelers and offering to carry them on her back like a horse. This punishment connects Rhiannon directly to equine identity, reflecting her original appearance on the supernatural white mare. Some scholars believe Rhiannon was originally a horse goddess similar to Epona, with her tale representing the diminishment of older goddess worship. The white mare that cannot be caught represents divine power beyond human control, making it one of the more subtle yet profound mythical mares in Celtic tradition.

The Mares of the Sun and Moon

In various mythological traditions, the sun and moon were believed to be pulled across the sky by divine horses or mares. In Greek mythology, Helios drove a chariot pulled by four horses (sometimes identified as mares) named Pyrois, Aeos, Aethon, and Phlegon, whose fiery nature reflected the sun’s burning power. Similarly, Selene, goddess of the moon, rode across the night sky in a chariot pulled by luminous white horses or mares whose coats reflected moonlight. Hindu mythology describes seven horses drawing Surya’s sun chariot, representing the seven days of the week and the seven colors of the rainbow. These celestial mares occupy a special category of mythical horses, as they perform the essential cosmic function of ensuring the sun and moon’s regular passage through the heavens. Their divine role in maintaining cosmic order places them among the most important mythical mares in religious traditions worldwide.

Mare of the Night: Nightmare Origins

The etymology of the word “nightmare” reveals a fascinating connection to mythical mares in European folklore. The term derives from the Old English “mare,” a malevolent female spirit that sat upon sleepers’ chests at night, causing terrifying dreams and sleep paralysis. This mare was often envisioned as having equine characteristics or associations, tying sleep disturbances to the image of a supernatural horse crushing the breath from sleepers. In Scandinavian and Germanic folklore, the “mara” or “mare” would ride humans during sleep, leaving them exhausted by morning, much as an overridden horse might be tired. Folk remedies against this night mare included placing horseshoes above beds—ironically using horse symbolism to ward off the equine nightmare spirit. This linguistic and folkloric connection between disturbing dreams and supernatural mares demonstrates how deeply horse imagery penetrated the human psyche in expressing primal fears.

Could the Most Mythical Mare Be Yet to Come?

While ancient mythical mares dominated traditional folklore, modern incarnations continue to evolve in contemporary media, suggesting the most mythical mare might still be emerging. Fantasy literature and films have revitalized equine mythology through characters like Shadowfax in Lord of the Rings, the Unicorns of The Last Unicorn, or the Black Stallion’s almost supernatural abilities in Walter Farley’s novels. Modern scientific understanding of horses combined with fantasy elements allows creators to develop increasingly complex mythical equines that incorporate both ancient symbolism and contemporary concerns. The digital age has also spawned new forms of mythical horses in games and virtual worlds, where they often possess abilities beyond any historical precedent. This continuous reinvention suggests that the concept of the mythical mare remains vital to human imagination, with each generation creating its own equine legends that build upon centuries of horse mythology.

Conclusion: The Immortal Appeal of Mythical Mares

When considering the question of the “most mythical mare,” we find no definitive answer but rather a tapestry of extraordinary equine figures that reflect human hopes, fears, and spiritual aspirations across cultures. From Al-Buraq’s lightning speed connecting earth and heaven to Loki’s mare form giving birth to an eight-legged wonder, these legendary horses transcend ordinary equine limitations while maintaining the essential qualities that make horses so compelling to humans. Perhaps the most mythical mare is not a single figure but the collective archetype itself—the divine feminine equine that appears across cultures as vehicle, companion, threat, and miracle-worker. As long as horses continue to captivate human imagination, mythical mares will gallop through our stories, dreams, and cultural consciousness, embodying the mysterious connection between humans and these magnificent animals that has endured throughout history.