In the sun-drenched landscapes of ancient Greece, few animals held as much reverence and practical significance as the horse. From the thundering hooves of battlefield chargers to the elegant steeds of Olympian athletes, horses were deeply woven into the fabric of Greek civilization. Their presence transcended mere utility, becoming embedded in mythology, art, warfare, sport, and social hierarchy. The relationship between Greeks and horses reflects a profound cultural partnership that helped shape one of history’s most influential civilizations. Through examining this equine legacy, we gain insight not only into the practical aspects of Greek life but also into the values, beliefs, and aesthetic sensibilities that continue to influence Western culture to this day.

The Divine Connection: Horses in Greek Mythology

Greek mythology abounds with equine figures that demonstrate the divine significance attributed to horses. Poseidon, god of the sea, was also known as “Earth-Shaker” and “Horse-Tamer,” believed to have created the first horse by striking his trident upon the ground. The winged horse Pegasus, born from the blood of Medusa after Perseus beheaded her, became one of mythology’s most enduring symbols, representing divine inspiration and artistic creation. Centaurs—half-human, half-horse beings—embodied the duality between human intellect and animal instinct, often featuring in tales warning of unbridled passion and the dangers of excess. The chariot of Helios, the sun god, was pulled by four horses as it traversed the sky each day, showing how Greeks viewed horses as connectors between the earthly and divine realms.

Horses as Status Symbols in Ancient Greek Society

Owning horses in ancient Greece was a clear declaration of wealth and social prominence, as the costs of purchasing, maintaining, and training quality horses put them beyond the reach of common citizens. The hippeis, or cavalry class in Athens, comprised the second-highest tier in the social hierarchy, illustrating how equestrian ability conferred political standing. Aristocratic families often adopted horse-related surnames or emblems on their coats of arms to emphasize their equestrian connections and, by extension, their noble lineage. The term hippotrophia—the breeding and maintenance of horses—was recognized as both a public service and a display of elite status, with wealthy citizens expected to provide horses for military and ceremonial purposes as part of their civic duty to the polis.

The Evolution of Greek Horsemanship

Greek horsemanship developed considerably over the centuries, evolving from rudimentary riding skills to sophisticated techniques that influenced equestrian traditions across the Mediterranean. Early Greeks initially rode bareback or used simple cloth pads, gradually adopting more advanced tack, including primitive saddles and bridles with metal bits by the 5th century BCE. The influential text On Horsemanship by Xenophon, written around 350 BCE, provided the first comprehensive guide to horse training, care, and riding, establishing principles that remained relevant for millennia. Archaeological evidence from vase paintings and reliefs shows the progression of riding styles, from the earliest depictions of awkward postures to the confident, balanced seat that would later influence Roman cavalry techniques.

Horses in Greek Warfare

The military application of horses transformed Greek warfare, though not in the way commonly depicted in popular culture. Unlike later cavalry traditions, Greek forces primarily used horses to transport hoplites (infantry soldiers) to battle rather than as direct fighting mounts until the Hellenistic period. The chariot, while featured prominently in Homeric epics like The Iliad, had largely been replaced by mounted cavalry by the Classical period, with specialized hippeis units becoming increasingly important in military strategy. Philip II of Macedon revolutionized Greek military techniques by developing a formidable cavalry force that his son Alexander the Great would later use to stunning effect in his conquests across Asia. The Thessalian cavalry was particularly renowned throughout Greece, employing the rhomboid formation that allowed for rapid changes in direction and effective flanking maneuvers against infantry formations.

Olympic Equestrian Events

Horse racing constituted some of the most prestigious and spectacular events in the ancient Olympic Games, with competitions including the tethrippon (four-horse chariot race) and the keles (mounted horse race) drawing massive crowds. Unlike modern Olympic traditions, the owner of the horse rather than the rider or charioteer received the victory crown, emphasizing how these contests served as displays of elite wealth and breeding acumen. The hippodrome at Olympia, measuring approximately 780 meters long and 320 meters wide, accommodated the thundering charge of competing teams while spectators gathered on surrounding hillsides to witness these dangerous and thrilling contests. Historical records note famous victories such as that of Cimon of Athens, who won the Olympic chariot race three consecutive times, and Alcibiades, who once entered seven chariots in a single Olympic competition, taking first, second, and fourth places.

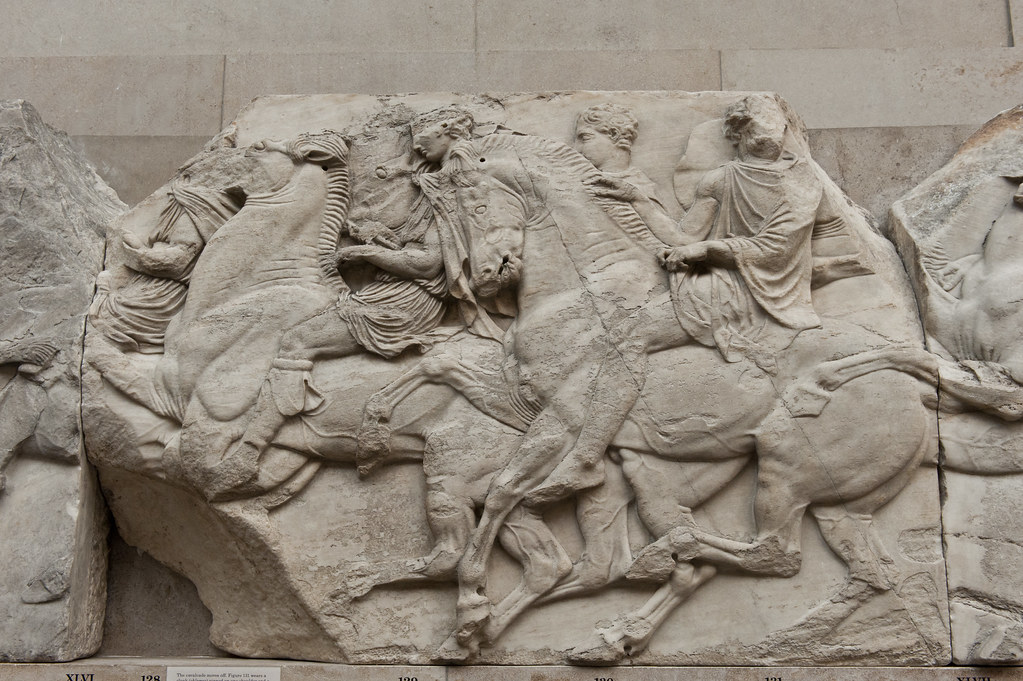

The Parthenon Frieze: Horses in Greek Art

Perhaps no artistic work better exemplifies the Greek reverence for horses than the magnificent Parthenon frieze, which features over 200 figures, with horses represented in extraordinary detail and grace throughout its 160-meter length. Sculptors of the frieze, created under the direction of Phidias in the 5th century BCE, portrayed horses with remarkable anatomical accuracy while simultaneously imbuing them with idealized beauty reflecting Greek aesthetic principles. The Panathenaic procession depicted in the frieze prominently features the Apobates contest, where athletic riders would leap on and off moving horses, demonstrating both equestrian skill and physical prowess. Art historians have noted that horses on the frieze are depicted with individual personalities and expressions, suggesting that Greeks recognized and celebrated the unique character of horses rather than viewing them as mere beasts of burden.

Horse Breeds and Physical Characteristics in Ancient Greece

The horses of ancient Greece were considerably smaller than modern breeds, typically standing 13–14 hands high (approximately 52–56 inches at the shoulder), closer in size to what we would now classify as ponies. Greek texts and artistic depictions suggest several distinct types were recognized, including the sturdy Thessalian horses prized for warfare and the lighter, faster Sicilian breed favored for racing competitions. Archaeological evidence from skeletal remains indicates these animals possessed strong bone structure despite their smaller stature, enabling them to carry adult riders effectively over varied terrain. Greek horse breeders selectively developed traits such as rounded haunches, broad chests, and proportionally large heads—characteristics still visible in some Mediterranean breeds like the modern Skyrian pony of Greece, believed to be descended from ancient stock.

The Greek Hippiatrika: Ancient Veterinary Practices

Greek concern for equine health produced some of the earliest veterinary texts in Western civilization, collectively known as the Hippiatrika, which compiled knowledge about horse diseases, treatments, and preventative care. These manuscripts described detailed anatomical observations and prescribed specific remedies for common ailments, from herbal poultices for leg swelling to surgical interventions for certain injuries. Writers like Aristotle included significant sections on equine biology in their natural philosophy works, noting behavioral patterns, reproductive cycles, and growth rates with remarkable accuracy for their time. Archaeological discoveries of specialized tools at certain sites suggest the existence of dedicated horse doctors or hippiatroi who treated valuable animals using methods derived from both practical experience and philosophical theories about bodily humors.

Mythical Horse Figures: Centaurs and Pegasus

The centaur—half-human, half-horse—represented a complex symbolic figure in Greek mythology, embodying the tension between civilization and wilderness, rationality and instinct. While most centaurs were depicted as wild and unruly creatures given to violence and excess, exceptions like the wise Chiron—tutor to heroes including Achilles, Jason, and Asclepius—showed how horse-human hybridity could also represent the highest integration of physical strength and intellectual wisdom. Pegasus, the winged horse born from Medusa’s blood, came to symbolize poetry and artistic inspiration, with the myth of his hoof creating the Hippocrene spring (whose waters conferred poetic ability) establishing a direct connection between horses and creative expression. These mythological equines appeared consistently across different art forms, from monumental sculpture to household items like painted vases, demonstrating their deep integration into Greek cultural consciousness.

Horse Taming and Training Techniques

Xenophon’s influential treatise On Horsemanship provides our most detailed account of Greek horse training methods, emphasizing gentle handling over harsh, dominance-based approaches that were common in some contemporary cultures. Greek trainers developed systematic desensitization techniques to accustom horses to battlefield conditions, gradually introducing them to fluttering fabrics, sudden movements, and loud noises to prevent panic during combat situations. The concept of working with a horse’s natural temperament rather than against it appears repeatedly in Greek writings, revealing a surprisingly modern understanding of equine psychology and learning patterns. Archaeological findings of specialized training equipment, including various bits designed for different training stages, confirm the sophisticated nature of Greek horsemanship and their investment in proper equine education.

Horses in Greek Literature and Poetry

From Homer’s epic descriptions to Pindar’s victory odes, horses gallop through Greek literature as symbols of nobility, divine favor, and the dynamic power of nature. The Iliad contains over 30 specific references to horses, including detailed passages about their lineage, appearance, and emotional states—such as the famous scene where Achilles’ immortal horses weep at Patroclus’ death. Sophocles’ tragedy Electra uses the false tale of Orestes dying in a chariot race accident as a pivotal plot device, with the vivid description of the disaster highlighting the dangerous yet glorious nature of equestrian competition. Lyric poets frequently employed horse imagery as metaphors for human experiences, with Anacreon comparing love to a powerful Thracian steed that requires skillful handling, and Sappho describing the bride in a wedding procession as a prized mare.

The Legacy of Greek Equestrian Culture

The Greek approach to horsemanship created ripple effects across subsequent civilizations, particularly influencing Roman cavalry tactics and breeding programs as the empire expanded eastward. Xenophon’s equestrian writings were preserved and studied throughout the medieval period and Renaissance, forming the foundation of classical dressage principles still practiced in elite riding academies today. Greek artistic conventions for depicting horses—particularly the distinctive “flying gallop” pose with all four legs extended—spread throughout the ancient world and continued to influence equine art for centuries, even appearing in early photographic studies of horse movement. Perhaps most enduringly, the Greek integration of horses into cultural, athletic, and military spheres established a model for human-equine partnership that transcended mere utility, recognizing these animals as collaborators worthy of care, study, and admiration—a perspective that continues to inform modern horsemanship philosophy.

The legacy of horses in ancient Greece extends far beyond their practical applications, representing a multifaceted relationship that touched every aspect of Greek civilization. From the divine realms of Olympus to the dust of the hippodrome, from battlefield formations to artistic masterpieces, horses galloped through Greek life as partners, symbols, and cultural touchstones. The sophistication of Greek horsemanship, their veterinary knowledge, and their artistic celebration of equine beauty all speak to a civilization that recognized something profound in their relationship with these animals. As we continue to study the artifacts, texts, and traditions they left behind, we discover that the hoofprints of Greek horses have left an indelible mark on Western culture, carrying forward ancient wisdom about the special bond between humans and these magnificent creatures.