The relationship between horses and the timber industry represents one of history’s most significant partnerships between humans and animals in a working environment. Before mechanization transformed logging operations, horses provided the crucial muscle power that enabled the harvesting of forests across North America, Europe, and beyond. These magnificent animals dragged massive logs from dense woodlands, traversed difficult terrain, and formed deep bonds with the lumberjacks who depended on them daily. Their contribution to building nations cannot be overstated—the lumber they helped harvest built cities, railroads, and industries during periods of explosive growth and westward expansion. The story of logging horses combines impressive feats of animal strength, specialized breeding programs, innovative equipment development, and the evolution of sustainable forestry practices—a fascinating chapter in our shared history that deserves recognition and remembrance.

The Rise of Horse-Powered Logging

The integration of horses into commercial logging operations gained significant momentum in the early 19th century as demand for timber exploded with growing populations and industrialization. Prior to this period, human muscle power and waterways were the primary means of moving timber, severely limiting the scope and scale of logging operations. Horses dramatically expanded logging capabilities by allowing lumbermen to access inland forests previously considered too remote for commercial harvesting. Their ability to navigate varied terrain while providing reliable, mobile power transformed the industry, enabling a boom in timber production that supported massive infrastructure development across North America and Europe. This revolution in logging methodology created entire communities centered around timber production, with horses serving as the essential link between forest and sawmill.

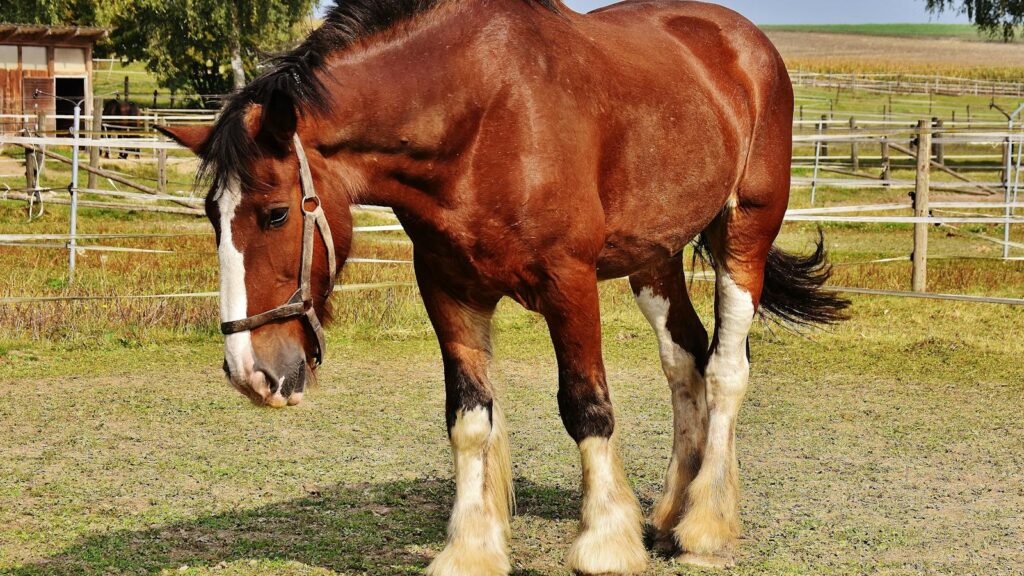

Breeds Preferred for Logging Work

Draft horses, specifically bred for their strength, stamina, and temperament, dominated the logging industry with several breeds rising to prominence based on regional preferences and availability. The massive Percherons, originating from France, became favorites in many operations due to their combination of power and relatively light bone structure that allowed them to maneuver through forest settings. Belgian draft horses earned their reputation through exceptional strength and a willing temperament that made them ideal partners in the dangerous work of skidding logs. The Suffolk Punch, with its shorter, more compact build, excelled in areas where lower center of gravity provided advantages on steep terrain. In North America, the Clydesdale also found its place in logging camps, particularly in regions with Scottish immigration influence, where their combination of strength and “feathered” feet (which provided protection in rough conditions) made them valuable workers in the woods.

Special Equipment and Harnesses

Logging horses required specialized equipment that balanced efficiency with animal welfare considerations, resulting in innovative harness designs specific to forest work. The collar harness, carefully fitted to each horse’s unique shoulder structure, distributed weight evenly to prevent injury during the tremendous pulling efforts required to move massive logs. Specialized britching (the posterior portion of the harness) allowed horses to hold back heavy loads when descending slopes—a critical safety feature in hilly terrain. Log chains, tongs, and specialized hooks connected harnesses to timber, with designs evolving over decades to maximize mechanical advantage while minimizing injury risk to the animals. Perhaps most distinctive was the development of specialized logging sleds, bobsleds, and “big wheels”—massive wooden wheels sometimes exceeding seven feet in diameter—that elevated the leading edge of logs to reduce drag and make previously impossible loads manageable for a well-trained team.

The Daily Life of a Logging Horse

The working life of a logging horse followed a regimented schedule that acknowledged both the demanding nature of the work and the valuable status of these animals within the operation. Days typically began before dawn with feeding and grooming sessions that maintained health and allowed teamsters to check for any injuries or issues requiring attention. During peak operations, horses might work 10-12 hour days pulling massive logs from cutting sites to landings or waterways, with rest periods built into the schedule to prevent exhaustion. Evening care routines were comprehensive and methodical—harnesses removed and cleaned, coats brushed to remove sweat and debris, hooves checked for injuries or lodged objects, and nutritionally-dense feed provided to restore energy. In winter camps, heated stables were often better constructed than the men’s quarters, reflecting the economic value and genuine affection these animals represented to logging operations that depended entirely on their wellbeing and performance.

Teamster Skills and Horse Management

The teamsters who worked with logging horses possessed specialized skills that combined animal psychology, mechanical knowledge, and wilderness experience in ways few other professions demanded. These men (almost exclusively male in historical operations) developed deep understanding of each animal’s personality, strengths, and limitations—knowledge that prevented accidents and maximized efficiency in dangerous conditions. Communication between teamster and horse relied on voice commands, precise rein signals, and body language that evolved into sophisticated systems allowing nuanced control over tremendous power. Proper feeding regimens became a science unto itself, with teamsters calculating precise nutritional requirements based on work intensity, weather conditions, and individual metabolism. The best teamsters gained legendary status in logging communities based on their ability to move impossible loads with minimal strain on their animals, demonstrating the deep partnership that developed between these skilled workers and the horses that responded to their guidance.

Skidding Techniques and Strategies

Log skidding—dragging felled timber from cutting site to collection points—required sophisticated techniques that evolved through generations of practical experience in diverse forest conditions. In flat terrain, straightforward ground skidding techniques prevailed, with horses pulling logs directly on soil or snow, sometimes using “skid pans” (curved metal plates) attached to log ends to reduce friction. For uphill extractions, block and tackle systems created mechanical advantage, allowing teams to move logs that would otherwise exceed their pulling capacity. In areas with deep snow, teamsters utilized “ice roads”—pathways deliberately flooded and frozen to create slick surfaces that dramatically reduced friction and allowed small teams to move surprisingly large loads. Perhaps most impressive were the “traverse skidding” techniques developed for sidehills, where horses moved laterally across slopes while controlling descending logs—work requiring exceptional training and coordination between animal and teamster to prevent dangerous runaways that could injure or kill both horse and handler.

Winter Logging Operations

Winter transformed logging operations, with snow and ice creating conditions that paradoxically made horse-powered timber extraction more efficient despite the harsh working environment. Frozen ground protected forest floors and root systems from damage that summer operations might cause, while providing solid footing where muddy conditions would otherwise make work impossible. Snow-packed roads allowed sleds to replace wheeled vehicles, dramatically reducing friction and enabling smaller teams to move larger loads than possible in warmer months. The preservation qualities of cold weather also benefited the horses themselves, eliminating the biting insects that tormented them during summer operations and reducing overheating risks during strenuous pulling efforts. Winter camps operated as nearly self-contained communities, with elaborate stable facilities, hay storage, and farrier shops ensuring horses remained healthy and productive during the critical high-production months when frozen conditions created peak efficiency for animal-powered logging.

River Drives and Horse Contributions

The spectacular river drives that moved timber to distant mills relied heavily on horse power during crucial preparation phases that determined the operation’s ultimate success. Horses dragged logs to riverbanks during winter months, creating massive piles strategically positioned for release when spring thaws raised water levels. Teams pulled logs across frozen waterways to create landing areas that would become launch points once ice melted in the spring thaw. When rivers began flowing, horses operated the mechanical winches and boom systems that controlled the flow of logs into waterways, preventing dangerous log jams that could halt entire operations. In smaller tributary streams where water volume proved insufficient for floating logs, horses would drag timber directly in stream beds, creating artificial “mini-drives” to reach main waterways—work that required horses to stand for hours in cold water, demonstrating their remarkable adaptability to challenging conditions.

The Transition to Mechanization

The gradual replacement of horse power with mechanized equipment began in earnest during the 1920s, though the transition occurred unevenly across different regions and operation types. Early tractors offered impressive power but lacked the maneuverability and adaptability that horses provided in challenging forest terrain, limiting their initial adoption to operations with relatively flat, open conditions. The economic pressures of the Great Depression ironically extended the era of horse logging in many regions, as cash-strapped operations couldn’t afford to invest in expensive machinery and maintenance. World War II accelerated mechanization by simultaneously creating labor shortages and driving technological development, making machinery more capable and horses less economically competitive. In remote areas with smaller operations, horses maintained their presence well into the 1960s, with some specialty logging and selective harvesting operations still utilizing horse power today for environmental sensitivity in delicate ecosystems where heavy machinery would cause unacceptable damage.

Notable Logging Horse Legends

The cultural history of logging contains remarkable stories of individual horses whose feats became legendary within timber communities. Perhaps most famous was “King,” a Percheron working in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula who reportedly pulled a load exceeding 50 tons on ice—a record that inspired debates and competitions throughout the northern forests. In Washington state, a Belgian named “Major” gained fame for his intelligence in navigating treacherous mountain slopes without direct guidance, seemingly understanding the physics of log movement better than some human workers. The tragic story of “Old Smokey,” a horse who died saving his teamster from a runaway log by pushing the man to safety, inspired poetry and songs still performed at logging heritage events today. These stories weren’t mere tall tales but represented the genuine admiration and emotional connections formed between loggers and the powerful animals whose partnership made their dangerous work possible, creating a rich folklore tradition that preserved the memory of these remarkable working animals.

The Economics of Horse Logging

The financial calculations surrounding horse-powered logging operations reflected complex considerations beyond simple comparisons of horsepower or fuel consumption. A working draft horse represented a substantial capital investment—equivalent to a skilled worker’s annual salary—yet offered 8-10 productive years when properly maintained, with residual value afterward for less demanding agricultural work. Daily operating costs included specialized feed requirements of 20-30 pounds of hay plus grain supplements, regular farrier service, veterinary care, and harness maintenance, all representing ongoing expenses that mechanized equipment would eventually replace with fuel and parts costs. While a single horse provided less raw power than early tractors, their maneuverability, self-maintenance capacity, and ability to reproduce represented advantages that kept them economically competitive surprisingly late into the industrial era. The calculation ultimately shifted when increasing labor costs and decreasing equipment prices reached a tipping point that varied by region, operation size, and terrain characteristics—explaining the uneven transition away from horse power that characterized the industry’s evolution.

Modern Horse Logging Revival

A remarkable resurgence in horse-powered logging has emerged since the 1990s, driven by environmental considerations, specialty timber markets, and cultural heritage preservation efforts. Modern horse logging operations specialize in low-impact selective harvesting where minimal ground disturbance preserves forest ecosystems, prevents erosion, and protects waterways—advantages that command premium prices from environmentally-conscious timber buyers. The refined techniques employed today combine traditional knowledge with modern forestry science, allowing precision extraction of high-value specimens while leaving surrounding trees undamaged. Educational programs have developed around this revival, with apprenticeship opportunities teaching both historical methods and contemporary adaptations that meet current forest management standards. Beyond practical applications, demonstration teams now appear at forestry exhibitions worldwide, preserving historical techniques while educating the public about sustainable timber harvesting alternatives to industrial clear-cutting approaches that dominated much of the 20th century.

Cultural Impact and Logging Heritage

The partnership between horses and loggers left an indelible mark on cultural heritage across timber regions, creating traditions, folklore, and community identities that persist long after the work itself has transformed. Logging horse competitions evolved from practical workday challenges into formalized events at agricultural fairs and timber festivals, where modern teamsters demonstrate historical skills to appreciative audiences. Museums dedicated to forest history prominently feature the role of horses, preserving harnesses, equipment, and photographs that document this crucial chapter in industrial development. The vocabulary of horse logging infused regional dialects with specialized terminology that appears in literature, music, and local expressions, preserving linguistic evidence of these working relationships. Perhaps most significantly, the ethical relationship between loggers and their horses—based on mutual dependence, respect, and care despite demanding conditions—established cultural values regarding animal welfare and proper stewardship that continue influencing attitudes toward working animals in modern society.

Horses and logging share an intertwined history that spans centuries and helped build nations through the harvest of forest resources. These magnificent draft animals provided the muscle that moved timber from remote forests to growing communities during crucial developmental periods, creating an irreplaceable legacy in both practical forestry techniques and cultural heritage. Though largely replaced by mechanization in commercial operations, the knowledge, equipment designs, and working relationships developed during the horse logging era continue influencing modern forestry practices. The revival of horse logging for specialized applications demonstrates the enduring value of these techniques in an era increasingly concerned with sustainable resource management. As we consider the environmental impacts of modern mechanized logging, the careful, selective approaches developed during the horse-powered era offer valuable lessons in balancing resource extraction with ecosystem preservation—a timeless wisdom born from the remarkable partnership between humans, horses, and forests.