Throughout human history, the theft of horses has represented more than simple property crime. Horses were vital for transportation, warfare, agriculture, and status—making them prime targets for thieves. From Wild West outlaws to military campaigns, the annals of history are filled with daring horse thefts that changed fortunes, influenced battles, and sometimes even altered the course of history itself. These notorious tales of equine larceny reveal not just criminal audacity but also the immense cultural and economic value placed on these magnificent animals across civilizations and centuries.

The Wild West Horse Thieves: A Hanging Offense

In the American frontier during the 19th century, few crimes were considered more severe than horse theft, often resulting in immediate execution without trial. The theft of a horse could leave a family without transportation, livelihood, or means of survival in the harsh western territories. Famous outlaws like the James-Younger Gang frequently incorporated horse theft into their criminal repertoire, understanding that mobility was essential to evading capture. The notorious hanging trees of places like Horse Thief Canyon in California stand as grim reminders of frontier justice, where suspected horse thieves would be strung up as warnings to others. This era established horse theft as one of the most serious crimes in American history, reflecting the animal’s essential role in western expansion and settlement.

Phar Lap: The Suspected Poisoning of a Racing Legend

While not a traditional theft, the suspected poisoning of champion racehorse Phar Lap in 1932 represents one of history’s most infamous attempts to “steal” a horse’s potential. This Australian racing sensation had won 37 of his 51 races, becoming a national icon during the Great Depression and frustrating many competing horse owners and gamblers. After traveling to compete in America, Phar Lap died suddenly under mysterious circumstances, with forensic analysis decades later suggesting arsenic poisoning. Many believed organized crime figures orchestrated his death to prevent him from dominating American races as he had in Australia. Though no physical theft occurred, Phar Lap’s case represents the extreme measures some would take to eliminate valuable equine competition, effectively stealing his future victories and earning potential.

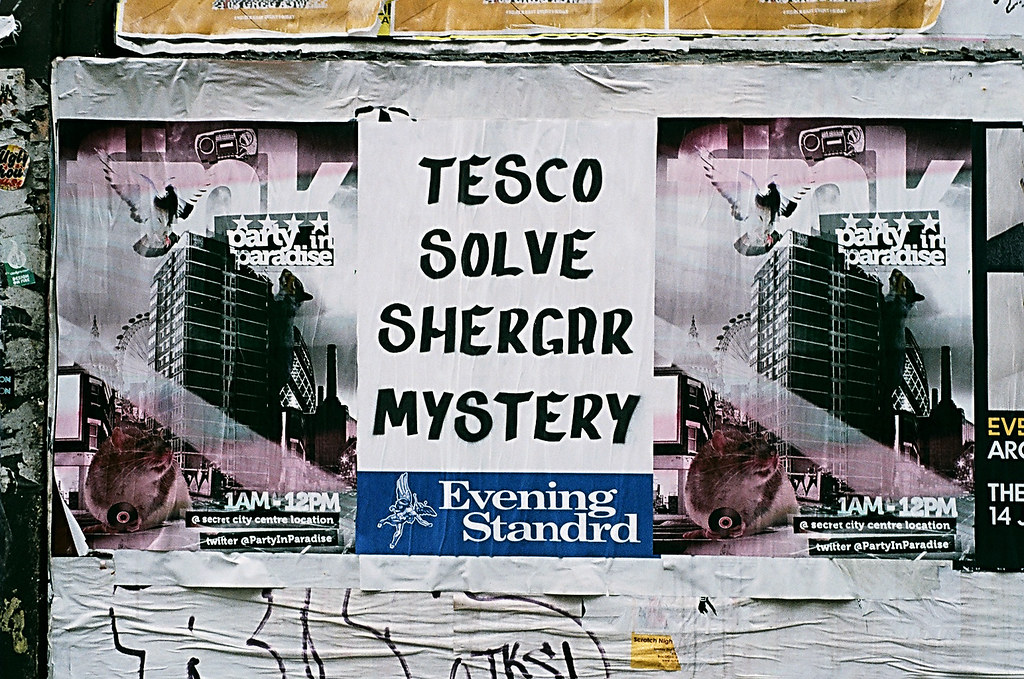

Shergar: The Kidnapping That Remains Unsolved

Perhaps the most famous horse theft in modern history is the 1983 kidnapping of Shergar, a champion thoroughbred valued at over $13.5 million. On February 8, 1983, armed men broke into Ballymany Stud Farm in County Kildare, Ireland, forcing Shergar’s groom to load the horse into a trailer before taking both captive. Though the groom was later released, Shergar was never found, with investigations pointing to the involvement of the Irish Republican Army seeking funds for their paramilitary activities. The kidnappers reportedly demanded a ransom of £2 million, but negotiations fell apart due to complications in the horse’s shared ownership structure. Despite extensive investigations, Shergar’s fate remains unknown, though most believe the horse was killed shortly after the abduction when the thieves realized they couldn’t manage such a recognizable animal.

Alexander the Great and Bucephalus: The Taming of the Untamable

While not exactly theft in the criminal sense, Alexander the Great’s acquisition of his legendary horse Bucephalus contains elements of appropriation that made it legendary. According to historical accounts, when Alexander was a young prince, he witnessed his father King Philip II of Macedon rejecting an extremely wild and seemingly untamable black stallion. Recognizing that the horse was afraid of its own shadow, the 12-year-old Alexander bet his father he could tame the beast, positioning the horse toward the sun so its shadow fell behind it. Successfully mounting and riding Bucephalus, Alexander effectively claimed a horse others couldn’t handle, “stealing” a prize from under the noses of more experienced horsemen. This horse became Alexander’s trusted mount during his conquest of the known world, carrying him through major battles until its death in 326 BCE, demonstrating how a single horse could shape history.

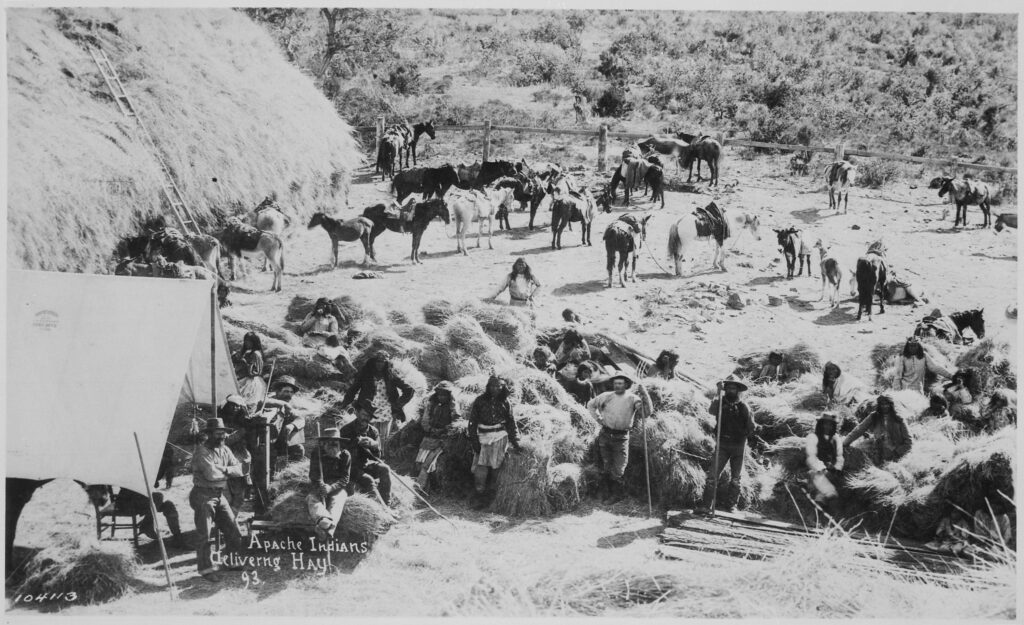

The Apache Horse Raids: Masters of Equine Strategy

The Apache tribes of the American Southwest developed some of history’s most effective horse theft techniques, elevating the practice to a strategic art form. After Spanish colonizers introduced horses to North America, Apache warriors conducted sophisticated raids on Spanish, Mexican, and later American settlements, specifically targeting horse herds. These weren’t simple smash-and-grab operations—Apache raiders studied their targets for days, used diversionary tactics, and could silently remove dozens or even hundreds of horses without alerting guards. The stolen horses transformed Apache mobility and military capability, allowing them to resist colonial encroachment for generations longer than might have otherwise been possible. Chief Victorio, one of the most successful Apache leaders of the late 19th century, was particularly known for his horse-stealing abilities, once reportedly taking over 100 horses from a cavalry post without a single shot being fired.

The Confederate Raid on Holly Springs: Cutting Grant’s Supply Line

During the American Civil War, one of the most consequential horse thefts occurred on December 20, 1862, when Confederate General Earl Van Dorn led a daring raid on Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s supply base at Holly Springs, Mississippi. The Confederate cavalry captured or destroyed millions of dollars worth of Union supplies and, critically, seized or disabled approximately 1,500 horses and mules essential to Grant’s campaign toward Vicksburg. This massive theft of equine resources forced Grant to abandon his initial strategy for capturing the vital Mississippi River stronghold, delaying the campaign by months. The Holly Springs raid demonstrated how targeted horse theft could disrupt major military operations, as armies of this era remained entirely dependent on horses for mobility, artillery transport, and supply chains. Van Dorn’s raid stands as perhaps the most strategically significant horse theft in American military history.

Frank Abagnale’s Horse Racing Con

The infamous impostor and con artist Frank Abagnale Jr., whose life story inspired the film “Catch Me If You Can,” pulled off an audacious horse-related theft in France during the 1960s. Rather than stealing physical horses, Abagnale conceived a scheme to steal their value by impersonating a horse owner and falsifying thoroughbred pedigree documents. By creating elaborate forgeries and gaining access to prestigious French racing circles, he managed to sell partial ownership shares in horses that either didn’t exist or weren’t as valuable as claimed. When authorities began closing in, Abagnale disappeared with hundreds of thousands of dollars, leaving numerous wealthy investors with worthless papers. This sophisticated scam demonstrated how horse theft had evolved from physical stealing to complex fraud operations targeting the immense financial ecosystem surrounding thoroughbred racing.

Rustling During the Texas-Mexico Border Conflicts

The borderlands between Texas and Mexico became notorious for cross-border horse theft operations throughout the 19th century, creating international tensions that sometimes escalated to armed conflict. Mexican bandits led by figures like Juan Cortina conducted large-scale raids into Texas, while Texas Rangers and vigilante groups responded with equally aggressive counter-raids into Mexican territory. These horse-rustling operations often targeted ranches owned by political or ethnic rivals, blurring the line between crime and unofficial warfare. The infamous “Skinning War” of the 1870s began with accusations of horse theft and escalated into a bloody conflict between Anglo ranchers and Mexican-American communities in South Texas. These border conflicts established patterns of retribution and cross-border tensions that would continue well into the 20th century, with stolen horses serving as both economic prizes and symbols of resistance against perceived oppressors on both sides.

The Theft of Napoleon’s White Stallion

During the chaotic aftermath of Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the emperor’s prized white Arabian stallion, Marengo, was captured by British forces. This magnificent horse, named after Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Marengo and his mount in numerous campaigns, represented far more than mere transportation—it symbolized imperial power and Napoleon’s military genius. Captain John Angerstein of the Grenadier Guards claimed the horse as a prize of war and brought it to England, where Marengo lived out its days as a celebrated curiosity and breeding stallion. For Napoleon, already suffering the humiliation of defeat and exile, the loss of his iconic horse represented a physical manifestation of his fallen empire. Marengo’s skeleton is still displayed at the National Army Museum in London, a permanent reminder of how the theft of a single horse came to symbolize the transfer of power from one empire to another.

The Great Comanche Horse Theft of 1840

In one of the most daring acts of equine larceny in American frontier history, Comanche warriors conducted a spectacular raid in 1840 that resulted in the theft of nearly every horse in San Antonio, Texas. Under cover of darkness, Comanche raiders silently entered the city and its surroundings, methodically gathering hundreds of horses from stables, corrals, and homesteads. By dawn, citizens awoke to find virtually the entire community’s horse population gone, crippling the settlement’s transportation, commerce, and defensive capabilities. The massive scale of the theft demonstrated the Comanche’s unparalleled horsemanship and knowledge of silent raiding tactics, as they were able to control and move hundreds of horses without creating alarm. This audacious theft strengthened the Comanche position as the dominant force on the Southern Plains, as they incorporated these horses into their already formidable mounted forces.

Edwin Mead: The Horse Thief Who Became a Lawman

The remarkable story of Edwin Mead illustrates the strange transformations possible in frontier America, where a notorious horse thief eventually became a respected lawman. Beginning his criminal career in the 1870s, Mead operated a sophisticated horse theft ring across Wyoming and Montana territories, using a network of accomplices to steal, rebrand, and sell horses across multiple states. After being captured and serving a prison sentence, Mead’s intimate knowledge of criminal methods made him valuable to law enforcement agencies struggling to combat the very crimes he once committed. Remarkably, he was hired as a detective for the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, where his insider knowledge of rustling techniques proved invaluable in catching other horse thieves. Mead’s transformation from thief to thief-catcher remains one of the most ironic tales in the history of horse theft, demonstrating how even criminal expertise could be repurposed for law enforcement in the developing West.

The Theft of Rienzi: Stealing a Union General’s Warhorse

During the American Civil War, Confederate soldiers executed a daring midnight raid to steal the famous black stallion Rienzi, the trusted mount of Union General Philip Sheridan. The theft occurred while Sheridan was attending a strategy meeting, with Confederate scouts having learned of the valuable horse’s location through their intelligence network. After stealing Rienzi from Union lines, the Confederate raiders believed they had struck a significant psychological and practical blow against the renowned Union cavalry commander, as Sheridan had ridden Rienzi in numerous successful campaigns. Upon discovering the theft, Sheridan reportedly offered a substantial reward for the horse’s return and dispatched cavalry units specifically to recover his prized mount. The horse was eventually recaptured during a counterraid on Confederate positions, allowing Sheridan to continue his campaign with his trusted warhorse—later renamed Winchester—whose speed and endurance were credited with helping turn the tide in critical battles of the war.

Australia’s Brumby Runners: Professional Horse Thieves

In the Australian outback during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a unique form of horse theft emerged with the rise of “brumby runners”—individuals who specialized in capturing and stealing wild horses (brumbies) that often included escaped or abandoned domestic horses. These professional thieves developed extraordinary skills in tracking, trapping, and breaking wild horses before selling them to unsuspecting buyers with falsified ownership papers. Unlike conventional horse thieves who targeted domesticated animals, brumby runners operated in a legal gray area by claiming they were simply capturing ownerless wild horses, even when evidence suggested some were recently escaped domestic animals still bearing partial brands. Famous brumby runners like Billy the Brumby and Harry “Horse-Snatcher” Wilson became legendary figures in Australian folklore, representing a uniquely Australian variant of horse theft that continued well into the 20th century. The practice became so problematic that special mounted police units were formed specifically to patrol remote areas and combat this specialized form of equine larceny.

The theft of horses throughout history represents far more than ordinary crime—it reflects the animal’s central role in human civilization across cultures and eras. From Wild West hangings to international kidnapping schemes, these stories reveal how horses have been valued not just as property but as symbols of power, freedom, and status. Whether motivated by financial gain, military advantage, or cultural resistance, horse thieves have left an indelible mark on our historical narrative. As we continue to value these magnificent animals in modern times—now more for sport and companionship than war and transportation—these notorious tales serve as reminders of the special relationship between humans and horses that has shaped civilizations and inspired both criminals and heroes throughout the ages.