In the golden sands of ancient Egypt, where monuments reach toward the heavens and hieroglyphs tell stories of gods and pharaohs, horses held a place of profound significance. Unlike the everyday beasts of burden found throughout other ancient civilizations, horses in Egypt were creatures of prestige, symbols of power, and companions in both life and death. Their inclusion in burial rituals reflects a complex relationship between Egyptians and these majestic animals—one that bridged the earthly realm and the afterlife. The archaeological evidence of horses in Egyptian tombs provides a fascinating window into the beliefs, social structures, and spiritual practices of one of history’s most enduring civilizations. Through examining these burial customs, we gain insight not only into how Egyptians viewed horses, but also how they conceived of the journey beyond death itself.

The Introduction of Horses to Ancient Egypt

Horses were not native to ancient Egypt, arriving relatively late in the civilization’s long history during the Second Intermediate Period (1650-1550 BCE), primarily through contact with the Hyksos. This foreign introduction transformed Egyptian military tactics, transportation, and eventually religious and funerary practices. Prior to the arrival of horses, Egyptians relied heavily on donkeys for transportation and oxen for agricultural work. The relative scarcity and foreign origin of horses immediately established them as prestigious animals, associated with wealth, power, and the ruling elite. Archaeological evidence suggests that early Egyptian interactions with horses were tentative, but by the New Kingdom period (1550-1070 BCE), horses had become firmly integrated into the fabric of Egyptian society and religious symbolism.

Symbolic Significance of Horses in Egyptian Culture

In Egyptian cultural symbolism, horses represented speed, strength, and divine connection—attributes particularly valued in the journey to the afterlife. They were frequently associated with the sun god Ra and his daily journey across the sky, with the horse’s swiftness mirroring the sun’s passage. The Egyptians believed that horses possessed keen spiritual senses, able to perceive supernatural beings and navigate between worlds. This perception made them ideal psychopomps—guides for the deceased in the treacherous journey through the underworld. Artistic representations often depicted horses with exaggerated features emphasizing their perceived supernatural qualities: elongated necks, prominent eyes, and powerful bodies that blended realistic observation with symbolic enhancement.

Horses as Status Symbols in Life and Death

The expense of maintaining horses in ancient Egypt meant they were primarily accessible only to royalty and the highest nobility, creating a natural association between horses and elite status. This exclusivity translated directly into funerary practices, where the inclusion of horses or horse-related items in a burial served as a powerful indicator of the deceased’s social standing. Pharaohs and nobles would be buried with horse trappings, chariots, and sometimes the animals themselves to demonstrate their continued status in the afterlife. Archaeological discoveries from tombs in Thebes and the Valley of the Kings reveal elaborate horse equipment made with gold, silver, and precious stones—investments that would have been substantial even for the wealthy elite. For those unable to afford actual horse burials, symbolic representations through art or figurines served as less costly alternatives.

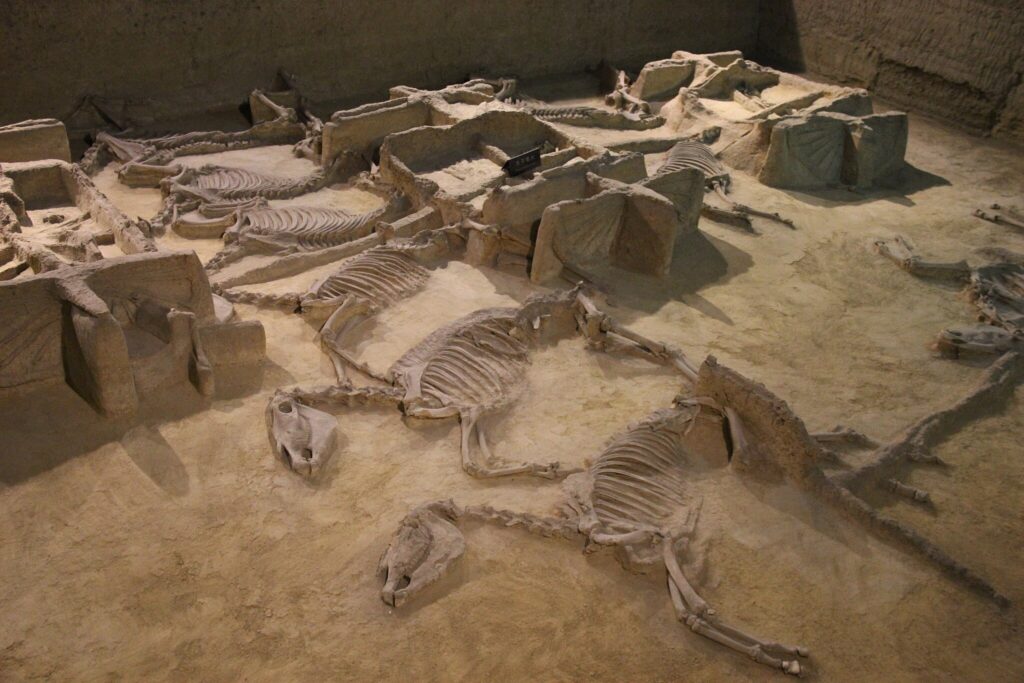

Archaeological Evidence of Horse Burials

Several remarkable archaeological discoveries have illuminated the practice of horse burials in ancient Egypt. The most notable example comes from the tomb of Amenhotep II (1427-1400 BCE), where six horses were found buried in a separate chamber, carefully arranged and adorned with ceremonial trappings. At Tell el-Dab’a (the ancient Hyksos capital of Avaris), archaeologists uncovered several horse burials dating to the Second Intermediate Period, suggesting the practice may have been introduced alongside the animals themselves. In the royal cemetery at Tanis, dating to the Third Intermediate Period, multiple horse tombs have been discovered, containing not only equine remains but also specialized grave goods including decorative bridles, blinders, and pectorals. These findings demonstrate that horse burials were not isolated incidents but rather an established practice spanning multiple dynasties and centuries.

The Chariot and Its Funerary Significance

The chariot, inseparable from horses in Egyptian military and ceremonial contexts, held tremendous importance in burial customs. Egyptians believed that the deceased would need transportation in the afterlife, with chariots representing both practical conveyance and symbolic status. Tomb art frequently depicted the deceased riding chariots drawn by horses to meet the gods or participate in eternal hunting expeditions. Physical chariot burials, such as those found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, featured carefully dismantled vehicles that could be “reassembled” in the afterlife, complete with wheels, axles, and body components crafted from precious materials. The associated horse equipment—including bridles, bits, and decorative elements—was often inscribed with protective symbols and spells designed to ensure safe passage. In royal tombs, specialized chambers were sometimes constructed specifically to house these important vehicles and their equine counterparts.

Mummification Practices for Horses

While human mummification in ancient Egypt is widely known, the mummification of horses represents a specialized practice reserved for animals of exceptional importance. Archaeological evidence reveals that horses selected for burial with elite individuals often underwent modified mummification procedures designed to preserve their bodies for the afterlife. Unlike human mummification, which involved the removal of internal organs, horse preparation typically focused on external preservation using natron (a natural salt mixture), resins, and wrappings. X-ray analysis of equine remains from New Kingdom tombs has revealed evidence of this treatment, showing careful positioning and sometimes internal support structures. The most elaborate horse mummifications included facial masks made of cartonnage (layers of linen or papyrus covered with plaster), gilded hooves, and eyes inlaid with semiprecious stones—treatments reflecting the animals’ elevated status.

Spiritual Beliefs Surrounding Equine Afterlife

The Egyptians held complex beliefs about animals in the afterlife, with horses occupying a unique position as both servants and companions to the deceased. Textual evidence from the Book of the Dead and tomb inscriptions suggests that horses were believed to retain their identity and relationship with their owners after death. The Egyptian concept of the ka (life force) and ba (personality) extended to important animals, with horses sometimes receiving their own funerary rites to ensure their successful transition to the afterlife. Magical spells and incantations found on horse trappings indicate attempts to protect these valuable companions during their journey through the underworld. Tomb art frequently portrays horses in idealized settings, participating in hunting, racing, or ceremonial activities—suggesting that Egyptians anticipated continuing these activities with their equine companions in the afterlife.

Funerary Horse Equipment and Artifacts

The horse equipment found in Egyptian tombs represents some of the most exquisite craftsmanship of the ancient world, combining practical design with spiritual protection. Bridles and headstalls recovered from royal tombs often feature gold and silver fittings, with decorative elements depicting protective deities like Taweret and Bes. Specialized funerary equipment included pectorals (chest ornaments) inscribed with the deceased’s name alongside the horse’s name, creating a permanent bond between owner and animal. Archaeological discoveries from the tomb of Yuya and Tjuyu (nobility from the 18th dynasty) included leather horse trappings with gold leaf applications depicting scenes of the deceased triumphant in battle. Many items show minimal signs of practical wear, suggesting they were created specifically for burial purposes—a testament to the resources dedicated to equipping horses for the afterlife journey.

Regional Variations in Horse Burial Practices

Archaeological evidence suggests that horse burial practices varied significantly across different regions of ancient Egypt, reflecting local traditions and foreign influences. In the Delta region, where Hyksos influence was strongest, horse burials tended to follow Near Eastern practices with complete horse interments often positioned near chariot components. Upper Egyptian sites show more variation, with some locations favoring symbolic representations over actual animal burials, possibly reflecting resource limitations or regional spiritual beliefs. Nubian-influenced areas in Egypt’s southern territories developed distinctive hybrid practices, incorporating both Egyptian symbolism and local funerary customs in horse burials. Temporal variations are equally significant, with practices evolving from the relative simplicity of Middle Kingdom representations to the elaborate physical burials of the New Kingdom and the return to predominantly symbolic inclusions during the Late Period when economic pressures constrained lavish burial practices.

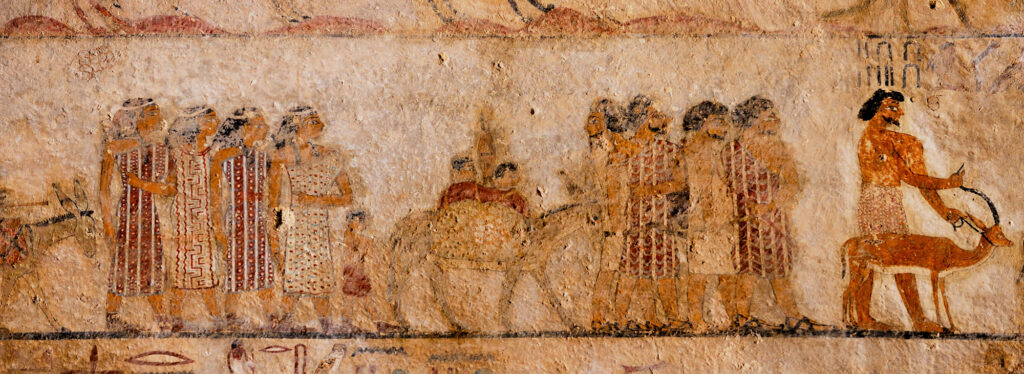

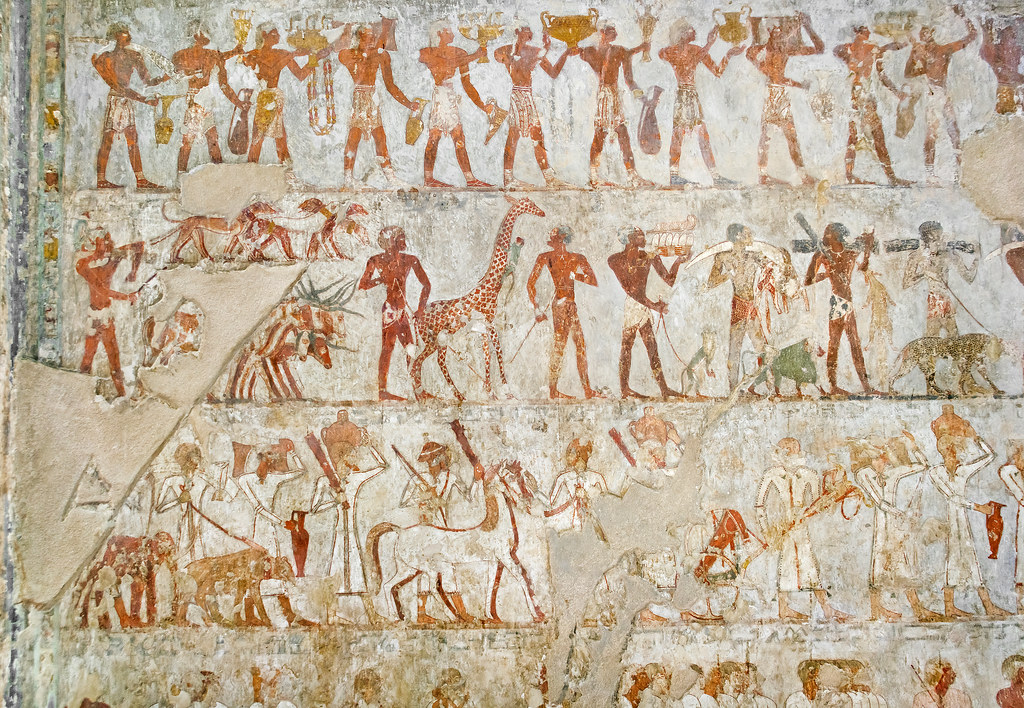

Horses in Tomb Artwork and Decoration

The walls of Egyptian tombs provide a rich visual record of horses in both earthly and afterlife contexts, offering insights beyond what physical remains alone can tell us. Painting and relief carvings typically portrayed horses with distinctive characteristics: arched necks, refined heads, and animated postures that conveyed their spirited nature. In the famous tomb of Userhet, a royal scribe during the reign of Amenhotep II, multiple scenes depict the deceased inspecting and feeding his horses, suggesting a personal connection that was expected to continue after death. The tomb of Rekhmire features elaborate chariot processions with horses adorned in ceremonial regalia, their movements captured with remarkable dynamism. These artistic representations followed strict canonical forms that evolved over time, with New Kingdom portrayals showing greater naturalism and attention to individual characteristics than earlier, more stylized depictions.

Horse Sacrifice: Debates and Evidence

The question of whether horses were sacrificed specifically for burial purposes in ancient Egypt remains a subject of scholarly debate, with archaeological evidence providing conflicting insights. Analysis of equine remains from royal tomb complexes has revealed that most buried horses were mature animals that had lived full lives, suggesting they may have been favorite steeds interred after natural death rather than sacrificial victims. However, some burial sites, particularly those associated with the cult of the sun god Ra, contain evidence of horses that died simultaneously, possibly indicating ceremonial sacrifice. Textual references from temple inscriptions suggest that horse sacrifice was practiced on rare occasions for specific religious ceremonies, particularly during the New Kingdom period. The ethical implications of horse sacrifice would have been significant given the immense value of these animals, likely limiting the practice to only the most important royal or religious contexts.

The Evolution of Horse Burial Practices Over Time

The practice of including horses in Egyptian burials evolved substantially throughout the dynastic periods, reflecting changing religious beliefs, economic realities, and foreign influences. Early examples dating to the Second Intermediate Period show relatively simple inclusions of horse equipment or artistic representations, likely reflecting the novelty of horses in Egyptian culture. The practice reached its apex during the New Kingdom, when full horse burials with elaborate trappings became features of royal and elite tombs, coinciding with Egypt’s imperial expansion and increased wealth. During the Third Intermediate Period, economic pressures led to a reduction in actual horse burials, replaced by symbolic representations and miniature models. By the Late Period and Ptolemaic era, Greek and Persian influences had altered traditional practices, with horse symbolism increasingly merged with Hellenistic funerary traditions while maintaining distinctly Egyptian spiritual associations.

Legacy and Modern Understanding

The study of horse burial practices in ancient Egypt continues to evolve as new archaeological techniques provide fresh insights into this fascinating aspect of Egyptian funerary culture. DNA analysis of equine remains from tomb contexts has revealed information about the breeding and origin of horses selected for burial, indicating they were often of the highest quality stock available. Advanced imaging techniques have allowed scholars to examine wrapped horse remains without disturbing them, revealing previously unknown details about preparation methods. Contemporary archaeological approaches now consider these burials within broader contexts of human-animal relationships and social power structures rather than as isolated curiosities. This evolving understanding helps illuminate not just how horses were buried, but what these practices reveal about Egyptian conceptions of life, death, status, and the complex relationship between humans and the animals that shared their journey into the afterlife.

The inclusion of horses in ancient Egyptian burial rituals represents far more than simple animal interment—it embodies a complex spiritual relationship that bridged life and afterlife. From their introduction as foreign prestige animals to their integration into profound religious symbolism, horses occupied a special place in Egyptian consciousness. The archaeological evidence of these practices—from physical remains to artistic depictions and textual references—provides a multi-faceted window into Egyptian beliefs about death, status, and the spiritual journey. As research continues, these ancient equine companions continue to tell their stories across millennia, helping us understand not just Egyptian burial customs, but the universal human tendency to seek companionship, even in death, from the animals we cherish in life.