The rolling hills of southern Africa have witnessed a remarkable relationship develop between humans and horses that transcends mere utility. Among the Zulu and Basotho peoples, horses have evolved from practical acquisitions to profound cultural symbols woven deeply into the fabric of tradition, identity, and heritage. This enduring connection, forged through centuries of coexistence, tells a fascinating story of adaptation, resistance, and cultural pride. Though horses are not indigenous to the African continent, their introduction forever transformed these two distinct yet interconnected cultures, creating traditions that continue to captivate and inspire to this day.

The Introduction of Horses to Southern Africa

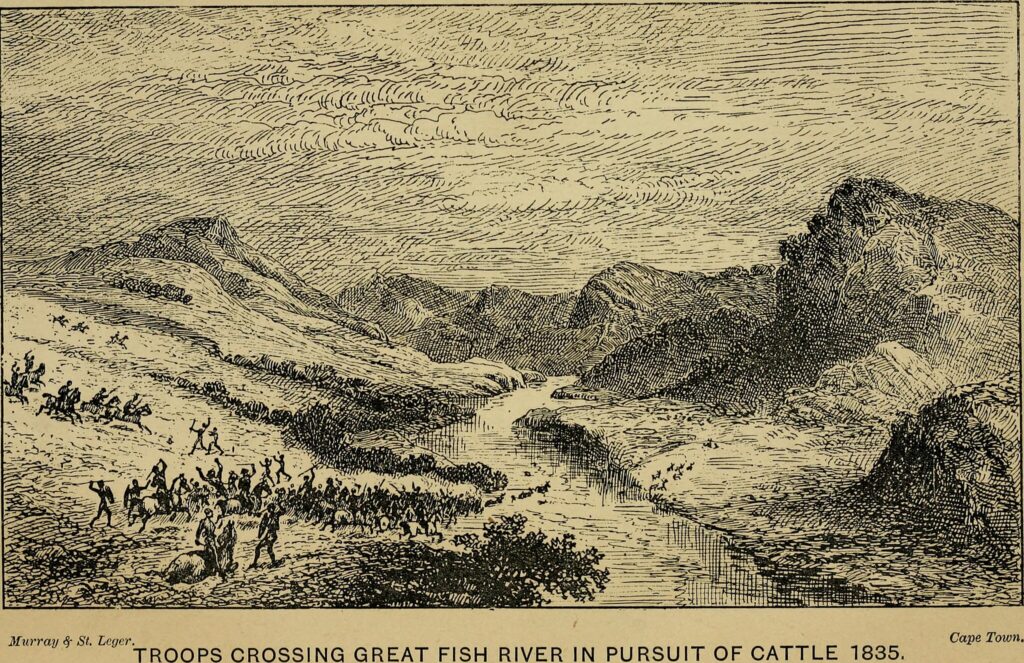

Horses first arrived in southern Africa with European settlers, primarily the Dutch who established a refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. These equine newcomers initially remained largely in European possession, with indigenous communities having limited access to them. It wasn’t until the late 18th and early 19th centuries that horses became more widely distributed among African communities, particularly through trade, warfare, and cultural exchange. For the Zulu and Basotho peoples, acquiring horses represented not just gaining a new animal, but embracing a transformative technology that would reshape their societies, military capabilities, and cultural identities in profound ways.

Horses in Zulu Military History

The incorporation of horses into Zulu military strategy marked a significant evolution from their traditionally infantry-based warfare. During King Shaka’s reign in the early 19th century, the Zulu were primarily known for their exceptional foot soldiers and innovative close-combat techniques. However, as horses became more accessible, Zulu commanders recognized their strategic advantage, particularly for reconnaissance, swift messenger services, and tactical mobility. By the time of the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879, mounted Zulu scouts played crucial roles in gathering intelligence and monitoring British movements. Though never adopted as widely as in the Basotho culture, horses enabled Zulu warriors to extend their operational range and respond more rapidly to threats against their kingdom.

The Horse as Symbol of Basotho National Identity

For the Basotho people, horses transcended their practical value to become the nation’s most recognizable symbol, even appearing prominently on Lesotho’s national flag. King Moshoeshoe I, the founder of the Basotho nation, strategically incorporated horses into his military and political strategy during the 1830s and 1840s, allowing his people to defend their mountainous homeland against numerous threats. The distinctive Basotho pony, a hardy breed adapted to the harsh mountain environment, became inseparable from Basotho identity. These small but remarkably sturdy animals enabled the Basotho to navigate their rugged terrain with unprecedented efficiency, transforming how they traveled, traded, and maintained their independence in the face of colonial encroachment.

The Development of the Basotho Pony

The Basotho pony emerged as a distinct breed through generations of natural selection and careful breeding in the challenging highlands of what is now Lesotho. Descended from horses brought by Dutch settlers, Indonesian ponies, and various European breeds, these animals evolved to thrive at high altitudes where oxygen is limited. Standing between 13 and 14.2 hands high, Basotho ponies are characterized by their exceptional endurance, sure-footedness on treacherous mountain paths, and remarkable hardiness in extreme weather conditions. Their compact bodies, strong legs, and incredible lung capacity make them perfectly adapted to navigate the steep, rocky terrain of the Maluti Mountains where larger, more delicate breeds would quickly falter.

Traditional Horsemanship Practices

Zulu and Basotho horsemanship developed distinctive characteristics reflecting each culture’s relationship with their environment and social structures. Basotho riders developed a unique style characterized by short stirrups, forward-leaning posture, and remarkable balance that allows them to navigate precipitous mountain trails with confidence. Young Basotho men traditionally begin riding from childhood, often starting without saddles to develop exceptional balance and connection with their mounts. Among the Zulu, horsemanship became associated with status and military prowess, with riders demonstrating skill through controlled maneuvers and disciplined formations. In both cultures, knowledge of horse behavior, care techniques, and riding skills has been passed down through generations through practical instruction and oral tradition.

The Symbolic Mokorotlo Hat

Perhaps no single item better represents the integration of horse culture into Basotho identity than the mokorotlo, the distinctive conical straw hat that has become a national symbol. The hat’s design is said to be inspired by the outline of Qiloane, a mountain peak near Thaba Bosiu, King Moshoeshoe’s mountain fortress. However, its practical function relates directly to horse culture – providing shade for riders traversing the high-altitude landscapes where sun exposure is intense. The mokorotlo appears on Lesotho’s national flag alongside a Basotho shield and knobkerrie (traditional weapons), with a silhouette of a Basotho pony completing this representation of national identity. Today, these hats remain a proud symbol worn during cultural celebrations, national events, and everyday life throughout Lesotho.

Horse Racing as Cultural Heritage

Horse racing evolved from practical skill demonstrations into elaborate cultural events that showcase horsemanship, community bonds, and cultural pride in both Zulu and Basotho societies. In Lesotho, traditional horse races draw massive crowds during national celebrations and local festivals, with jockeys often riding without saddles to demonstrate their exceptional balance and communion with their mounts. These races involve not just speed contests but displays of riding skill, with participants sometimes performing standing maneuvers at full gallop. Among the Zulu, particularly in rural KwaZulu-Natal, horse racing events combine competition with cultural ceremonies, featuring traditional dress, music, and rituals that celebrate both equestrian prowess and broader cultural heritage.

Horses in Basotho Oral Traditions

The profound impact of horses on Basotho society is preserved in a rich tradition of oral poetry, songs, and proverbs that celebrate the special relationship between riders and their mounts. These lithoko (praise poems) often personify horses as noble partners in adventure, describing their speed, endurance, and loyalty in vivid, metaphorical language. Basotho oral historians have preserved detailed accounts of famous horses that carried chiefs and warriors through significant historical moments, attributing to them personalities and qualities that elevate them beyond mere animals to historical actors in their own right. Traditional songs recount journeys across mountain passes, daring escapes from enemies, and the deep bond between a man and his trusted pony, with melodies that sometimes mimic the rhythmic pace of a cantering horse.

Ceremonial Significance in Zulu Culture

Within Zulu traditions, horses gained ceremonial significance beyond their practical applications, particularly in events celebrating masculinity, coming-of-age, and royal status. During important ceremonies such as umkhosi (royal gatherings), mounted regiments would perform synchronized riding displays demonstrating both horse control and unit discipline. White horses hold special significance in Zulu cosmology, sometimes associated with ancestral spirits or used specifically in certain ritual contexts by traditional healers (sangomas). At traditional Zulu weddings, a groom might arrive on horseback, symbolizing his status and ability to provide for his new family, with the horse adorned in special decorative coverings that reflect family patterns and symbols.

The Role of Horses in Modern Transportation

Despite modernization and the introduction of motorized vehicles, horses remain vital for transportation in many remote areas of Lesotho and rural KwaZulu-Natal. In Lesotho’s mountainous interior, where roads are scarce or impassable during harsh winters, Basotho ponies continue to serve as primary transportation for accessing healthcare, markets, and schools. These resilient animals transport heavy loads of supplies, agricultural products, and building materials across terrain inaccessible to vehicles. Health workers often rely on horseback to reach isolated communities, carrying medical supplies and providing care to populations that would otherwise remain cut off from essential services. This continued practical reliance on horses helps preserve traditional knowledge about breeding, care, and riding techniques that might otherwise fade in the face of modernization.

Economic Impact and Tourism

The distinctive equestrian traditions of the Zulu and Basotho peoples have evolved into significant cultural tourism attractions, creating economic opportunities while preserving heritage. In Lesotho, guided pony treks through the dramatic mountain landscapes have become a cornerstone of the country’s tourism industry, providing employment for guides, stable managers, and support staff. Cultural villages throughout KwaZulu-Natal and Lesotho showcase horsemanship demonstrations that attract visitors eager to witness these living traditions. The breeding and trading of quality horses, particularly Basotho ponies, contributes to rural economies and provides income for families who maintain traditional breeding knowledge. Additionally, annual horse racing festivals draw domestic and international visitors, generating revenue for local communities through accommodations, food services, and the sale of traditional crafts.

Challenges and Conservation Efforts

The traditional horse cultures of the Zulu and Basotho face significant challenges in the 21st century, from economic pressures to environmental concerns. The purebred Basotho pony population has declined precipitously due to crossbreeding with larger horses, prompting conservation initiatives aimed at preserving this unique breed’s genetic integrity. Organizations like the Lesotho National Conservation Society work with local communities to identify and preserve exemplary specimens of traditional Basotho ponies through selective breeding programs. Climate change presents additional challenges, with more frequent droughts affecting grazing lands and water availability for horses across southern Africa. Additionally, as younger generations migrate to urban areas for education and employment, traditional knowledge about horsemanship risks being lost unless deliberately preserved through formalized training programs and cultural heritage initiatives.

Living Heritage: Horses in Contemporary Cultural Celebrations

The enduring relationship between horses and these cultures lives on in vibrant contemporary celebrations that blend tradition with modern expressions of cultural identity. The annual Morija Arts & Cultural Festival in Lesotho features spectacular horse races and horsemanship demonstrations that attract participants and spectators from across southern Africa. In KwaZulu-Natal, events like the Royal Zulu Reed Dance now often include mounted escorts for dignitaries, incorporating horses into traditional ceremonies in ways that emphasize continuity with the past while acknowledging cultural evolution. Schools in both regions increasingly incorporate lessons about traditional horsemanship into cultural education programs, ensuring young people understand this aspect of their heritage even if they don’t personally ride. These living traditions demonstrate how successfully both cultures have integrated an initially foreign animal into their deepest expressions of identity and community.

Conclusion: The Enduring Bond

The story of horses in Zulu and Basotho culture illustrates how deeply an introduced animal can become integrated into a society’s identity, transforming from novelty to necessity to cultural cornerstone. Through centuries of adaptation and innovation, these communities developed unique relationships with horses that reflect their specific environments, historical challenges, and cultural values. Today, as both societies navigate the complex interplay between tradition and modernity, horses remain powerful symbols of heritage, independence, and cultural pride. Whether climbing mountain paths in Lesotho or participating in ceremonial displays in KwaZulu-Natal, these horses and their riders continue a living tradition that connects contemporary practitioners to their ancestors and preserves distinctive cultural knowledge for future generations.