Throughout human history, horses have been more than just beasts of burden or companions in battle—they have been powerful symbols of nobility, freedom, and divine connection. Ancient civilizations across the globe memorialized these magnificent creatures in their art and sculpture, creating enduring masterpieces that continue to captivate us thousands of years later. From the delicate grace of Greek sculptures to the powerful war horses of ancient China, these artistic representations tell us not only about the aesthetic values of their creators, but also about the profound relationship between humans and horses in ancient societies. This exploration of iconic equine art takes us on a journey through time and across continents, revealing how horses were venerated, depicted, and immortalized in stone, clay, and precious metals by our ancestors.

The Horses of San Marco: Venice’s Bronze Treasures

Standing proudly above the main entrance of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, the Horses of San Marco represent one of the most famous equine sculptures from antiquity. Originally created in the 2nd or 3rd century BCE, these life-sized bronze horses are remarkable for their anatomical accuracy and dynamic posture. The horses have a complex history—looted from Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, then taken to Paris by Napoleon in 1797, before finally being returned to Venice in 1815. What makes these sculptures particularly striking is their original gilding, traces of which can still be seen today, suggesting they once gleamed like golden apparitions in the Mediterranean sun. Today, the originals are preserved inside the basilica, while replicas stand in their place on the façade, continuing to symbolize Venetian power and artistic excellence.

Alexander the Great’s Bucephalus: A Horse of Legend

Perhaps no horse in ancient art carries more historical significance than Bucephalus, the legendary steed of Alexander the Great who appears in numerous artistic depictions throughout the ancient world. According to historical accounts, Bucephalus was a massive black stallion with a distinctive white star on his forehead, considered untamable until the young Alexander conquered him. The most famous representation comes from the Alexander Mosaic found in Pompeii, which dramatically portrays Alexander riding Bucephalus into battle against the Persian king Darius. Ancient sculptors also created numerous bronze and marble sculptures of this iconic pair, emphasizing the horse’s powerful musculature and proud bearing. These artistic representations helped cement Bucephalus as not just a historical animal but a symbol of conquest and the special bond between a legendary leader and his equally legendary mount.

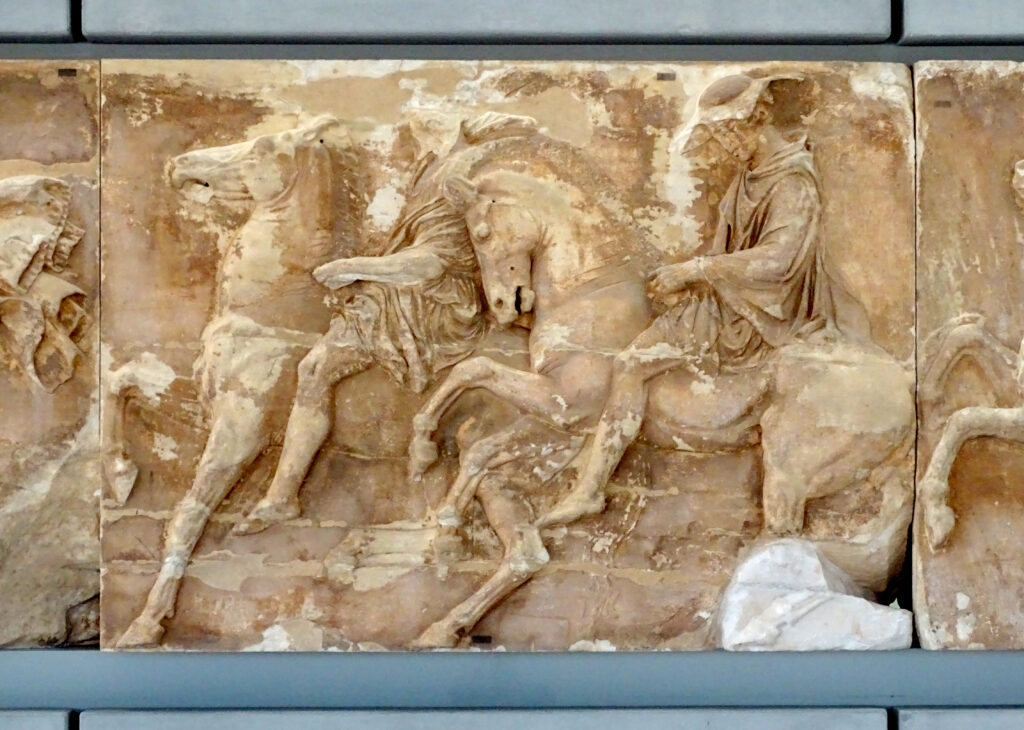

The Parthenon Frieze Horses: Athenian Marble Marvels

The Parthenon in Athens features one of the most extensive and remarkable collections of horse imagery in ancient art through its magnificent frieze. Carved between 442-438 BCE under the guidance of the sculptor Phidias, the frieze depicts the Panathenaic procession with approximately 200 horses portrayed with extraordinary attention to detail and movement. The horses of the Parthenon frieze are particularly notable for their anatomical accuracy and the way they capture the natural movement of horses in various gaits. What makes these sculptures revolutionary is how they convey a sense of living muscle beneath the marble surface, with flared nostrils, tensed necks, and the subtle shifting of weight that characterizes actual horses in motion. Through these sculptures, we can appreciate the intimate knowledge ancient Greek artists had of equine anatomy and behavior, as well as the central role horses played in Athenian religious and civic life.

The Terracotta Army Horses: Guardians of Emperor Qin

When the first Emperor of unified China, Qin Shi Huang, prepared for his afterlife around 210 BCE, he included an army of life-sized terracotta warriors—and among them, remarkably detailed clay horses. Discovered in 1974 near Xi’an, the terracotta army includes approximately 520 horses and 130 chariots, all created with astonishing realism and individuality. Each horse stands approximately 1.7 meters tall and weighs over 200 kilograms, with unique details in their musculature, posture, and facial expressions. What makes these sculptures particularly fascinating is that they were originally painted in bright colors—traces of pigments reveal that the horses were depicted with brown, black, white, and reddish coats, bringing an additional layer of realism to these already impressive sculptures. These horses represent the importance of cavalry in ancient Chinese warfare and symbolize the emperor’s power, with the meticulous attention to detail reflecting the Chinese belief that these sculptures would serve the emperor in the afterlife.

The Assyrian Palace Reliefs: War Horses in Stone

The ancient Assyrians were master horsemen who developed sophisticated cavalry tactics, and their palace walls immortalized these crucial military companions in dramatic limestone reliefs. Dating primarily from the 9th to 7th centuries BCE, the most spectacular examples come from the palaces at Nineveh and Nimrud, where horses are portrayed with remarkable attention to their tack, musculature, and movement during hunting expeditions and battle scenes. The Assyrian artists had a particular talent for conveying the energy and power of horses in action, showing them galloping with extended limbs, rearing in battle, or drawing royal chariots with heads held high. What distinguishes these reliefs is their documentary quality—they provide detailed information about how horses were harnessed, armored, and utilized in warfare, making them valuable not just as art but as historical records. The dramatic scenes of lion hunts, with horses portrayed in moments of intense action and emotion, remain some of the most dynamic equine representations in ancient art.

The Horse of Selene: Parthenon’s Moonlit Wonder

Among the sculptures that once adorned the Parthenon, the Horse of Selene from the east pediment stands out as one of the most emotionally evocative equine portrayals in ancient art. Created around 438-432 BCE, this marble masterpiece depicts the horse of Selene, goddess of the moon, as it descends below the horizon at dawn. The sculpture captures a moment of sublime natural beauty, with the horse’s head lowered and nostrils flared as if struggling against exhaustion after pulling the moon chariot through the night sky. What makes this sculpture particularly remarkable is how the artist has conveyed the horse’s fatigue through subtle anatomical details—the sunken eye, the distended veins, and the way the neck muscles strain as the head pulls downward. Now housed in the British Museum, this fragment of the Parthenon pediment demonstrates the Greek sculptors’ ability to infuse stone with emotion and narrative depth, creating not just an anatomically correct horse but one whose very being conveys the cosmic drama of day following night.

The Horses of Tarquinia: Etruscan Equine Frescoes

The Etruscan civilization of pre-Roman Italy left behind remarkable tomb paintings that feature horses prominently, with the most spectacular examples found in the necropolis of Tarquinia. Dating from approximately the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, these vivid frescoes depict horses in contexts ranging from chariot races to hunting scenes to funerary processions. The Tomb of the Olympic Games and the Tomb of the Augurs contain particularly striking depictions of horses rendered in profile with bold outlines and flat areas of color that give them a distinctive, lively stylization. What makes these paintings particularly valuable is how they document aspects of Etruscan life and beliefs while demonstrating a unique artistic approach that bridges Greek influence and indigenous Italian traditions. The horses in these tomb paintings are notable for their animated expressions, decorative harnesses, and the way their movements are captured with a sense of joyous energy that contrasts with the somber setting of the tombs themselves.

The Pergamon Altar Horses: Dramatic Battle Steeds

The Great Altar of Pergamon, constructed in the 2nd century BCE in what is now Turkey, features one of the most dramatic battle friezes from antiquity, with horses playing a central role in the depicted struggle between gods and giants. The sculptors of Pergamon created horses with unprecedented dynamism—rearing, twisting, and lunging through the marble as their divine riders engage in cosmic combat. What sets these equine sculptures apart is their extreme emotionality and the way they embody the violent energy of battle, with flared nostrils, wild eyes, and contorted bodies that seem to defy the stone from which they’re carved. The sculptors used deep drilling techniques to create shadow effects and a sense of three-dimensionality that was revolutionary for its time. Now housed primarily in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, these dramatic horse sculptures represent the height of Hellenistic sculptural achievement, where technical virtuosity meets emotional intensity to create horses that seem to transcend their marble medium.

The Rampin Rider: Early Greek Equestrian Mastery

Dating from approximately 550 BCE, the Rampin Rider represents one of the earliest masterpieces of Greek equestrian sculpture and marks a crucial development in the artistic portrayal of horses. This limestone statue from the Archaic period depicts a young aristocrat (kouros) mounted on a horse, with only fragments of both rider and mount surviving today. The horse portion, though fragmentary, reveals the early Greek understanding of equine anatomy with its powerful chest, sturdy neck, and the suggestion of movement through the positioning of the legs. What makes this sculpture historically significant is how it demonstrates the transition from the more stylized representations of earlier periods toward the naturalism that would characterize Classical Greek art. The statue also reflects the social importance of horsemanship among the Athenian aristocracy, where equestrian skills were markers of elite status and breeding. Now divided between the Louvre and the Acropolis Museum, the Rampin Rider represents a pivotal moment in the artistic journey toward the realistic portrayal of horses in Western art.

The Pazyryk Carpet Horses: Frozen in Time

In 1949, archaeologists made an astonishing discovery in the frozen tombs of Pazyryk in the Altai Mountains of Siberia—the oldest known pile carpet in the world, dating from the 5th century BCE, featuring remarkably detailed horse imagery. Preserved for over 2,500 years by ice, this carpet displays 24 horsemen in alternating colors, each riding stylized yet recognizable horses rendered with distinctive Scythian artistic conventions. What makes these horse representations particularly remarkable is their cultural fusion—combining Persian artistic motifs with the nomadic horse culture of the Eurasian steppes. The horses on the carpet are shown with distinctive feathered manes, decorated saddles, and bridles that provide valuable information about how these nomadic peoples adorned their most valuable possessions. This extraordinary textile, now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, demonstrates how central horses were to the identity and artistic expression of these ancient nomadic peoples who lived and died by their relationship with these animals.

The Iberians’ Sacred Horse: Guardians of the Afterlife

The ancient Iberians of the Spanish peninsula created distinctive horse sculptures that served important religious and funerary purposes between the 6th and 1st centuries BCE. The most famous example is “The Lady of Elche’s Horse,” a limestone sculpture from the necropolis of El Cigarralejo that depicts a stylized horse with simplified forms yet powerful presence. What distinguishes these Iberian horse sculptures is their function as psychopomps—spiritual guides believed to transport souls to the afterlife—and their distinctive decorative elements including geometric patterns carved into the stone representing horse trappings. The flattened, somewhat abstract quality of these sculptures reveals an indigenous artistic tradition that absorbed some Greek influences while maintaining its unique character. Archaeological evidence suggests these horse sculptures were often placed at burial sites of warriors and nobles, underlining the connection between horses, elite status, and spiritual transition in Iberian culture.

The Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Statue: Rome’s Bronze Survivor

Standing today in the Capitoline Museums in Rome, the equestrian statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius represents the only fully intact bronze equestrian statue to survive from ancient Rome. Created around 175 CE, this monumental work stands nearly 14 feet tall and portrays the philosopher-emperor astride a powerful horse that seems to be moving forward with its right foreleg raised. What makes this statue particularly remarkable is its survival—it escaped the medieval melting pots that claimed most ancient bronze statues because it was mistakenly identified as Constantine, the first Christian emperor. The horse is portrayed with striking naturalism—from the carefully modeled musculature to the veins visible beneath the skin—while maintaining an imperial dignity that matches its imperial rider. This statue became the template for Renaissance and later equestrian monuments, influencing artists from Donatello to Bernini, and represents the culmination of Roman equestrian sculptural tradition that integrated both artistic excellence and political symbolism into a unified masterpiece.

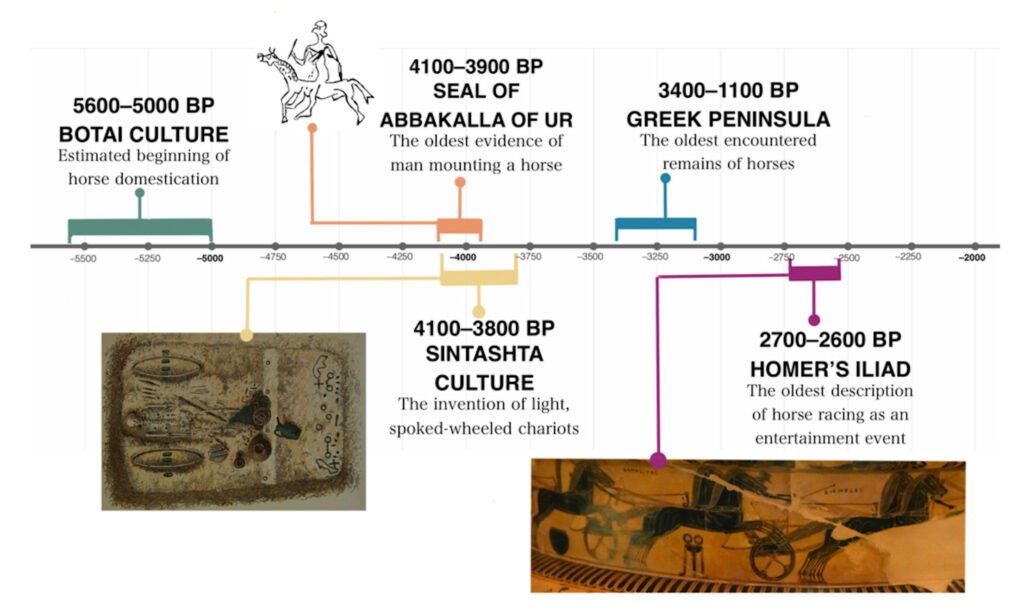

The Botai Culture Horse Artifacts: Dawn of Domestication

In the steppes of Kazakhstan, the ancient Botai culture created some of the earliest known artistic representations of domesticated horses around 3500 BCE, offering us glimpses into the very beginnings of the human-horse relationship. Archaeological excavations have revealed carved horse figurines made from bone and clay, as well as tools decorated with horse motifs that demonstrate how central these animals were to one of the earliest horse-domesticating cultures. What makes these artifacts particularly significant is their primitive yet recognizable equine forms, created at a pivotal moment when humans were transitioning from hunting horses to partnering with them. The stylized nature of these early horse representations—with elongated bodies, simplified heads, and emphasized manes—shows an already developing artistic tradition focused on the animal that was revolutionizing human mobility and subsistence. These humble artifacts, though lacking the technical sophistication of later horse art, represent the dawn of humanity’s artistic celebration of an animal that would transform civilization and be commemorated in art for millennia to come.

Conclusion

The iconic horses of ancient art and sculpture serve as a powerful reminder of the profound relationship humans have shared with these magnificent animals throughout history. From the earliest clay figurines of the Botai culture to the sophisticated bronze masterpieces of Rome, horses have galloped through the artistic imagination of civilizations across time and geography. These equine representations do more than showcase artistic techniques—they reveal cultural values, religious beliefs, military prowess, and social hierarchies. The remarkable consistency with which ancient peoples chose to immortalize horses in their most important art speaks to the universal recognition of these animals as symbols of power, freedom, and nobility. As we admire these surviving masterpieces today, we glimpse not only the artistic achievements of our ancestors but also their intimate understanding of an animal that helped build civilizations and capture the human imagination for thousands of years.